Thursday, 27 December 2012

New Year's Performance Review

Wednesday, 26 December 2012

WW: Into a new year

Thursday, 20 December 2012

Hermitcraft: Chai

It's Christmas, when thoughts naturally turn to chai. Well, they do if they're mine. Chai is not in fact a Christmas drink; it's the daily beverage of India, a nation that hardly has Christmas at all. (And the word itself simply means "tea". Like salsa [sauce] and baguette [stick], it's a humdrum, general term that English turned into a fancy, specific one.)

But chai is warm like Christmas, sweet like Christmas, and spicy like Christmas. It's the ultimate comfort food, and as good as it is all year, it's especially good now.

The trick to good chai is to mind the honey and not be Nordic with the spices. Hence the downfall of commercial efforts here in North America: too sweet, too bland.

Many years ago I set out to develop the perfect chai recipe. I spent months at it, pushing this, pulling that, until I arrived at the recipe below. I have since received favourable reviews from a wide variety of guests, from tea and chai connoisseurs to rank beginners. And from more than one Indian, a fact of which I am inordinately proud.

So in honour of the season, I share with all interested my most valuable possession. Wield it wisely.

PERFECT CHAI (or: Kensho in a Cup)

For one oversized mug or two teacups:

1 1/2 cups cold water

1/2 cup milk

2 teaspoons strong black loose tea, or two teabags of same*

1/2 teaspoon minced gingerroot

Two inches of cinnamon stick, shredded

2 cloves

1 teaspoon whole coriander seeds

2 cumin seeds (I mean it. Two seeds.)

2 peppercorns

1/2 teaspoon whole cardamom seeds

1 teaspoon anise seeds

a pinch of orange zest, if desired (adds bitterness if the tea leaves aren't strong enough, but go easy)

Enough honey to make drinking pleasant; typically about two teaspoons.

For a pot:

3 cups cold water

1 cup milk

4 teaspoons strong black loose tea, or four teabags of same*

1 teaspoon minced gingerroot

4 cloves

2 teaspoons whole coriander seeds

3 cumin seeds

1/2 teaspoon plus 1/4 teaspoon whole cardamom seeds

3 inches cinnamon stick, shredded

3 peppercorns

2 teaspoons anise seeds

orange zest, as above

About four teaspoons of honey.

*Any strong black tea will do. If using teabags, cut them open and dump the leaves in loose. (Always the best policy, even when brewing ordinary tea.)

Place all ingredients in a saucepan and warm gently. Mind that the chai doesn't boil; it shouldn't even bubble. Heat for a minimum of 20 minutes; 45 or better is optimum. (If you plan to steep the chai more than two hours, omit one peppercorn.) Strain into cups, returning the spices to the pot between rounds.

Chai can be made ahead and refrigerated, as long as it's reheated gently. It's also good chilled.

Chai arhats know that success in this powerful alchemy, regardless of recipe, relies on the Four Noble Truths:

1. All ingredients must be infused together. Do not add milk or honey at the table.

2. Chai is all about the spices; if you can taste the honey, it's over-sweet.

3. Boiling is fatal. It flattens the water, exhausts the spices, and burns the milk.

4. A good masala is equal parts quantity and variety. Cumin and peel counter sweetness, and should be just barely detectable. Cloves, pepper, cinnamon, cardamom, and coriander provide mouth and aroma and should be pronounced, without however overpowering the cup. And, crucially: the digestives (anise, ginger, milk, honey) make the whole thing possible. Without them you've got a harsh, even nauseating, stew. If your chai comes out coarse on the tongue or hard on the stomach, pump these up.

Chai goes wherever cocoa goes. Take it carolling, or to football games, or serve it at parties. It's also a famous after-meal digestive. I have chai with breakfast most Sundays, steeped during the morning sit.

So from all of us here at Rusty Ring, many happy returns of the season, and best wishes for the new year.

But chai is warm like Christmas, sweet like Christmas, and spicy like Christmas. It's the ultimate comfort food, and as good as it is all year, it's especially good now.

The trick to good chai is to mind the honey and not be Nordic with the spices. Hence the downfall of commercial efforts here in North America: too sweet, too bland.

Many years ago I set out to develop the perfect chai recipe. I spent months at it, pushing this, pulling that, until I arrived at the recipe below. I have since received favourable reviews from a wide variety of guests, from tea and chai connoisseurs to rank beginners. And from more than one Indian, a fact of which I am inordinately proud.

So in honour of the season, I share with all interested my most valuable possession. Wield it wisely.

PERFECT CHAI (or: Kensho in a Cup)

For one oversized mug or two teacups:

1 1/2 cups cold water

1/2 cup milk

2 teaspoons strong black loose tea, or two teabags of same*

1/2 teaspoon minced gingerroot

Two inches of cinnamon stick, shredded

2 cloves

1 teaspoon whole coriander seeds

2 cumin seeds (I mean it. Two seeds.)

2 peppercorns

1/2 teaspoon whole cardamom seeds

1 teaspoon anise seeds

a pinch of orange zest, if desired (adds bitterness if the tea leaves aren't strong enough, but go easy)

Enough honey to make drinking pleasant; typically about two teaspoons.

For a pot:

3 cups cold water

1 cup milk

4 teaspoons strong black loose tea, or four teabags of same*

1 teaspoon minced gingerroot

4 cloves

2 teaspoons whole coriander seeds

3 cumin seeds

1/2 teaspoon plus 1/4 teaspoon whole cardamom seeds

3 inches cinnamon stick, shredded

3 peppercorns

2 teaspoons anise seeds

orange zest, as above

About four teaspoons of honey.

*Any strong black tea will do. If using teabags, cut them open and dump the leaves in loose. (Always the best policy, even when brewing ordinary tea.)

Place all ingredients in a saucepan and warm gently. Mind that the chai doesn't boil; it shouldn't even bubble. Heat for a minimum of 20 minutes; 45 or better is optimum. (If you plan to steep the chai more than two hours, omit one peppercorn.) Strain into cups, returning the spices to the pot between rounds.

Chai can be made ahead and refrigerated, as long as it's reheated gently. It's also good chilled.

Chai arhats know that success in this powerful alchemy, regardless of recipe, relies on the Four Noble Truths:

1. All ingredients must be infused together. Do not add milk or honey at the table.

2. Chai is all about the spices; if you can taste the honey, it's over-sweet.

3. Boiling is fatal. It flattens the water, exhausts the spices, and burns the milk.

4. A good masala is equal parts quantity and variety. Cumin and peel counter sweetness, and should be just barely detectable. Cloves, pepper, cinnamon, cardamom, and coriander provide mouth and aroma and should be pronounced, without however overpowering the cup. And, crucially: the digestives (anise, ginger, milk, honey) make the whole thing possible. Without them you've got a harsh, even nauseating, stew. If your chai comes out coarse on the tongue or hard on the stomach, pump these up.

Chai goes wherever cocoa goes. Take it carolling, or to football games, or serve it at parties. It's also a famous after-meal digestive. I have chai with breakfast most Sundays, steeped during the morning sit.

So from all of us here at Rusty Ring, many happy returns of the season, and best wishes for the new year.

Wednesday, 19 December 2012

WW: Pet bluegill

Thursday, 13 December 2012

Christmas Kyôsaku

Topics:

Christmas,

kyôsaku,

Stephen Levine,

The Rusty Ring Art Gallery

Wednesday, 12 December 2012

WW: Flicker

Wednesday, 5 December 2012

WW: Not a black and white photo

Thursday, 29 November 2012

Humility Kyôsaku

While on a trip to another village, Nasrudin lost his favourite copy of the Qur'an.

Several weeks later, a goat walked up to Nasrudin, carrying the Qur'an in its mouth.

Nasrudin couldn't believe his eyes. He took the precious book out of the goat's mouth, raised his eyes heavenward and exclaimed, "It's a miracle!"

"Not really," said the goat. "Your name is written inside the cover."

From the Tales of Nasrudin.

(Photo courtesy of George Chernilevsky and Wikimedia Commons.)

Wednesday, 28 November 2012

Thursday, 22 November 2012

Thanksgiving Prayer

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be

That no life lives forever;

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.

Algernon Charles Swinburne

(Photo of a work-weary Columbia shuffling past the Astoria bridge to the Pacific, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Gene Daniels, and the US Environmental Protection Agency.)

Topics:

Columbia River,

gratitude,

hermit practice,

poem,

river,

Thanksgiving

Wednesday, 21 November 2012

Wednesday, 14 November 2012

WW: Bonnie bouk o' boletes

Topics:

autumn,

food,

hermitcraft,

mushroom,

wild edibles,

Wordless Wednesday

Thursday, 8 November 2012

Ajahn Brahm's Five Types of Religion

You gotta love Ajahn Brahmavamso Mahathera. He's a forest monk, albeit not of the hermit lineage. In a West dominated by Zen, Vipassana, and Vajrayana, his dharma is Theravada. He's a working class Englishman with a Cambridge degree in theoretical physics, trained as a monk in Thailand, and teaching in outback Australia. He runs a monastery he built himself. (Seriously. With his own hands.) And he's been excommunicated by his lineage. So he must be doing something right. (Ordaining women, as it happens.)

But the best thing about Ajahn Brahm is his teaching. There's precious little piety about this guru. He'll call out hypocrisy so fast it'll make your incense burner spin. And he starts with his own.

I particularly esteem Brahm's (in)famous Five Types of Religion. (True fact: the original teaching was Five Types of Buddhism, which is how I first heard it. Only when it was pointed out that all religions suffer from these delusions did he rework it for everyone.)

So here they are. Readers who practice a religion, any religion, should copy and paste this list. Then edit out my commentary, and meditate on the rest. Often.

Everybody strapped in?

AJAHN BRAHM'S FIVE TYPES OF RELIGION

1. Conceited Religion: Our religion is better than yours. (And therefore we are better than you.)

This is a Christian stereotype here in the West, but that's only because they're the majority; I run into identical Buddhists all the time. Despite what some would have you believe, triumphalism (the belief that you have a monopoly on truth) is a sin in every religion. In fact, I learned both the term and the condemnation as part of my Christian training.

2. Ritual Religion: Venerating the container above the contents.

Did someone say "guru worship"? Let's face it, Zenners: we do the hell out of this one. Obsession with rank and form, bowing, chanting, posture, oryoki, lighting this, ringing that, bop-she-bop, rama-lama-ding-dong. None of it's worth a crock of warm spit, and if you forget that, it's a giant waste of time.

3. Business Religion: We're best because we're biggest. Biggest church, largest sangha, highest priest, trendiest teacher-author.

This is the "success" model, whereby we declare the biggest seller the best product. Uh, no. Read your scripture, people. God doesn't like "success". Not least because it instantly becomes an altar to Mara. Worldly religion is no religion.

4. Negative Religion: We gotta GET those [insert group here] !!!

As Brahm points out, this is yin to Type 1's yang: where Conceited Religion says "we're the best," Negative Religion says "they're the worst." I call it Varsity Religion: lots of cheerleaders shaking their pompons and urging us to spend our meagre days on earth beating State. Good thing it has nothing to do with enlightenment; State can't be beat.

5. Real Religion: Doing what your prophet told you to do.

Note that the first four types are not this. Try it. Grab any religion. I like Zoroastrianism. And not just because it has the awesomest name of any religion. (It would be worth it to convert just so you could tell people you're Zoroastrian.)

Thus:

1. Did Zoroaster teach his followers that they were a superior race, and all others inferior?

No.

2. Did he teach that temporal gestures were the main point of faith?

No.

3. Did he teach that the biggest temples or most acclaimed priests were the most godly?

No.

4. Did he teach that life is all about opposing some other group?

Almost. He did say that Earth is a battleground between the godly and ungodly, and that salvation is a matter of enlisting in the correct army. But he didn't identify any earthly group as Angra Mainyu's army, nor did he say that just being a Zoroastrian automatically puts you in Ahura Mazda's. So…

No.

So there you have it. Grand Master Z agrees: "Walk the line, chump."

If you'd like to see Ajahn Brahm teach this truth himself (and I heartily recommend it, he's very engaging), you'll find it on YouTube. For links to many more Brahm talks, check out r/thaiforest's Ajahn Brahm Wiki via Reddit.

And yes, they're all that good.

(Photograph of seeker panning out Oz gold courtesy of WikiMedia and the State Library of Victoria.)

But the best thing about Ajahn Brahm is his teaching. There's precious little piety about this guru. He'll call out hypocrisy so fast it'll make your incense burner spin. And he starts with his own.

I particularly esteem Brahm's (in)famous Five Types of Religion. (True fact: the original teaching was Five Types of Buddhism, which is how I first heard it. Only when it was pointed out that all religions suffer from these delusions did he rework it for everyone.)

So here they are. Readers who practice a religion, any religion, should copy and paste this list. Then edit out my commentary, and meditate on the rest. Often.

Everybody strapped in?

AJAHN BRAHM'S FIVE TYPES OF RELIGION

1. Conceited Religion: Our religion is better than yours. (And therefore we are better than you.)

This is a Christian stereotype here in the West, but that's only because they're the majority; I run into identical Buddhists all the time. Despite what some would have you believe, triumphalism (the belief that you have a monopoly on truth) is a sin in every religion. In fact, I learned both the term and the condemnation as part of my Christian training.

2. Ritual Religion: Venerating the container above the contents.

Did someone say "guru worship"? Let's face it, Zenners: we do the hell out of this one. Obsession with rank and form, bowing, chanting, posture, oryoki, lighting this, ringing that, bop-she-bop, rama-lama-ding-dong. None of it's worth a crock of warm spit, and if you forget that, it's a giant waste of time.

3. Business Religion: We're best because we're biggest. Biggest church, largest sangha, highest priest, trendiest teacher-author.

This is the "success" model, whereby we declare the biggest seller the best product. Uh, no. Read your scripture, people. God doesn't like "success". Not least because it instantly becomes an altar to Mara. Worldly religion is no religion.

4. Negative Religion: We gotta GET those [insert group here] !!!

As Brahm points out, this is yin to Type 1's yang: where Conceited Religion says "we're the best," Negative Religion says "they're the worst." I call it Varsity Religion: lots of cheerleaders shaking their pompons and urging us to spend our meagre days on earth beating State. Good thing it has nothing to do with enlightenment; State can't be beat.

5. Real Religion: Doing what your prophet told you to do.

Note that the first four types are not this. Try it. Grab any religion. I like Zoroastrianism. And not just because it has the awesomest name of any religion. (It would be worth it to convert just so you could tell people you're Zoroastrian.)

Thus:

1. Did Zoroaster teach his followers that they were a superior race, and all others inferior?

No.

2. Did he teach that temporal gestures were the main point of faith?

No.

3. Did he teach that the biggest temples or most acclaimed priests were the most godly?

No.

4. Did he teach that life is all about opposing some other group?

Almost. He did say that Earth is a battleground between the godly and ungodly, and that salvation is a matter of enlisting in the correct army. But he didn't identify any earthly group as Angra Mainyu's army, nor did he say that just being a Zoroastrian automatically puts you in Ahura Mazda's. So…

No.

So there you have it. Grand Master Z agrees: "Walk the line, chump."

If you'd like to see Ajahn Brahm teach this truth himself (and I heartily recommend it, he's very engaging), you'll find it on YouTube. For links to many more Brahm talks, check out r/thaiforest's Ajahn Brahm Wiki via Reddit.

And yes, they're all that good.

(Photograph of seeker panning out Oz gold courtesy of WikiMedia and the State Library of Victoria.)

Topics:

Ajahn Brahm,

Australia,

Buddhism,

Christianity,

guru worship,

hermit practice,

mindfulness,

monastery,

monk,

podcast,

Theravada,

Zen

Wednesday, 7 November 2012

WW: Best houseboat ever

Thursday, 1 November 2012

Good Song: Won't Back Down

This week I'm posting a video tribute to Fudo, patron bodhisattva of my monastic practice.

I chose John's cover for the sole reason that his voice sounds like Fudo's own to me. (Minus the Scottish accent.) Plus I get a certain adolescent sursum corda from this interpretation. But Tom's original is also great.

So burn on, brother. Here in hell, you lose until you win.

I chose John's cover for the sole reason that his voice sounds like Fudo's own to me. (Minus the Scottish accent.) Plus I get a certain adolescent sursum corda from this interpretation. But Tom's original is also great.

So burn on, brother. Here in hell, you lose until you win.

Topics:

bodhisattva,

Fudo Myō-ō,

hermit practice,

John Cash,

music,

Tom Petty,

video

Wednesday, 31 October 2012

Wednesday, 24 October 2012

WW: Robin in the huckleberries

Wednesday, 17 October 2012

Thursday, 11 October 2012

Koan: Ole and Lena

Ja, times is sad down dere in Ambivalence Bay, shoor. Old Ole's lyin upstairs in da bed, he passed on just last night, and da family's cryin and carryin on, and everybody's in and out, gettin ready for da last rites.

Ja, times is sad down dere in Ambivalence Bay, shoor. Old Ole's lyin upstairs in da bed, he passed on just last night, and da family's cryin and carryin on, and everybody's in and out, gettin ready for da last rites.So all da women's fillin da kitchen wid lefse and cakes and finally night comes and da house is all quiet. Up in da bedroom Ole smells all dem good tings, and it wakes im up! He comes downstairs and sees all dat on da table and tinks, "I musta gone ta heaven!"

He reaches out to take a piece o wunada cakes, and suddenly Lena smacks his hand.

"Don't you touch dat!" she says. "Dat's for da funeral!"

Wu Ya's commentary: "Respect the forms, for Christ's sake!"

(Photo courtesy of PD Photo and Jon Sullivan.)

Wednesday, 10 October 2012

WW: My cowboy grandfather, Crooked River, 1918

Topics:

First Nations,

fossil or artefact,

Gold Side,

horse,

Wordless Wednesday

Wednesday, 3 October 2012

Monday, 1 October 2012

Reality Check Kyôsaku

"I do not say there is no Chàn.

Just no teachers."

Huangbo

(Photo of Evasterias troschelii [mottled seastar] fry, on the underside of a rock. The orange guy is about 2 inches long.)

Topics:

beach,

Chàn,

guru worship,

hermit practice,

Huangbo,

invertebrate,

kyôsaku,

Puget Sound,

starfish

Thursday, 27 September 2012

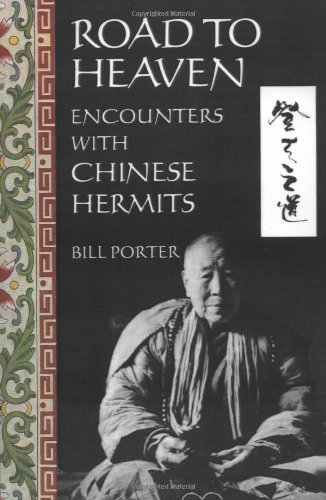

Good Book: Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits

In Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits, Bill Porter writes:

"Throughout Chinese history, there have always been people who preferred to spend their lives in the mountains, getting by on less, sleeping under thatch, wearing old clothes, working the higher slopes, not talking much, writing even less - maybe a few poems, a recipe or two. Out of touch with the times but not with the seasons, they cultivated roots of the spirit, trading flatland dust for mountain mist."

He ends with a declaration: "Distant and insignificant, they were the most respected men and women in the world's oldest society."

Road to Heaven is the memoir of Porter's 1989 hunt for Buddhism in the People's Republic of China. Theorising that in order to survive Mao's earth-scorching Cultural Revolution, any true practice would have had to return to its ancestral source, he spurned monasteries and struck out for the badlands. Which is already intriguing: an ordained cœnobite and authority on Buddhist scripture, with sixteen published translations to his name (and his ordination name, Red Pine), who respects hermit monks.

His journey starts at the toe of the Zhongnan Mountains, China's vast, rugged outdoor monastery, where Porter and a photographer friend drop by every ancient religious site he can find in the texts. It's depressing: landmark after landmark razed to the ground, or turned to profane ends by the Red Guards; books burned, practice banned, monks killed. There are still clerics around, but they live more like bureaucrats than monks. And they assure Porter that "nowadays, all monks live in temples." (I guess some wars are truly global.)

But Porter persists. Armed with fluent language skills, he follows a trail of hearsay off the pavement, and then off the road, and finally, in one instance, up a long chain bolted to a cliff. (Incredibly, he's given run of the Red Chinese outback, though The Man does contribute a few scary moments.) And up there, on the howling peaks where they've been for seven thousand years, he finds a whole flagrant hermit nation, pounding their ancient path as if the 20th century had never happened. And I'm not being glib; one subject interrupts him to ask, "Who is this 'Mao' you keep talking about?"

As the chronicle unfolds, Porter pieces together a practice that anticipates the Buddha by four and half millennia. It's œcumenical and anticlerical, and often not Buddhist at all: about three quarters of the hermits Porter meets are Taoists. And it turns out that they are the ones obsessed with nontheism and koanic thought and oneness. Thus the oxymoron of Zen Buddhism: the "Zen" part, isn't Buddhist.

Porter puts his profession to work for the reader, bringing in Taoist texts little known in the West, and fleshing out a religion that is a great deal more than Lao Tzu. Nor does he despise eremitic discipline. One informant tells him you must mix Pure Land and Zen equally, or the imbalance will throw you off the Dharma. (Taoism strikes again.) Another says he neither meditates nor chants: "I just pass the time." "Trying to stay alive keeps me pretty busy," agrees a female hermit, then tosses in a statement that should be carved on every hermit's lintel: "Practice depends on the individual. This is my practice."

Not all of the hermits Porter finds live in deep seclusion. Some have built sparse "neighbourhoods" in the mountains, cabins scattered within shouting distance of one another, and some have formed sketes, small numbers of hermits living under one roof. They also recognise urban eremitical vocations. But most striking for me was their universal self-respect. "These are the [Zhongnan] Mountains," states one. "This is where monks and nuns come who are serious about their practice."

Published in 1993, the text has a slightly dated feel, owing to the use of old-style transliterations (i.e., Chungnan rather than Zhongnan). Its resemblance to Amongst White Clouds, Edward A. Burger's documentary on the same topic, is due to the fact that Burger took his inspiration from the Porter book. But where the film is necessarily summary, Porter takes full advantage of his literary medium to go deeper, investigate nuance, and pursue explanations. Where Burger implies, perhaps by oversight, that all Chinese hermits pledge to a teacher, Porter finds Buddhist Associations (parishes) that require no permission at all to sit in their jurisdiction. And as I speculated in my review of the Burger movie, Porter does indeed encounter Zhongnan hermits who reject the notion of separate religions entirely.

The book finishes on a note both hopeful and challenging, not just to China but to Buddhism the world over. Just before leaving the country, Porter happens upon what had for centuries been a thriving urban monastery. Long empty, the place has recently been occupied, in the Wall Street sense, by a knot of Zen hermits. They brook no hierarchy; they have no abbot. And though their new home is falling apart, they are in no rush to restore it; the decay keeps the tourists away.

And they've come to practise.

"Throughout Chinese history, there have always been people who preferred to spend their lives in the mountains, getting by on less, sleeping under thatch, wearing old clothes, working the higher slopes, not talking much, writing even less - maybe a few poems, a recipe or two. Out of touch with the times but not with the seasons, they cultivated roots of the spirit, trading flatland dust for mountain mist."

He ends with a declaration: "Distant and insignificant, they were the most respected men and women in the world's oldest society."

Road to Heaven is the memoir of Porter's 1989 hunt for Buddhism in the People's Republic of China. Theorising that in order to survive Mao's earth-scorching Cultural Revolution, any true practice would have had to return to its ancestral source, he spurned monasteries and struck out for the badlands. Which is already intriguing: an ordained cœnobite and authority on Buddhist scripture, with sixteen published translations to his name (and his ordination name, Red Pine), who respects hermit monks.

His journey starts at the toe of the Zhongnan Mountains, China's vast, rugged outdoor monastery, where Porter and a photographer friend drop by every ancient religious site he can find in the texts. It's depressing: landmark after landmark razed to the ground, or turned to profane ends by the Red Guards; books burned, practice banned, monks killed. There are still clerics around, but they live more like bureaucrats than monks. And they assure Porter that "nowadays, all monks live in temples." (I guess some wars are truly global.)

But Porter persists. Armed with fluent language skills, he follows a trail of hearsay off the pavement, and then off the road, and finally, in one instance, up a long chain bolted to a cliff. (Incredibly, he's given run of the Red Chinese outback, though The Man does contribute a few scary moments.) And up there, on the howling peaks where they've been for seven thousand years, he finds a whole flagrant hermit nation, pounding their ancient path as if the 20th century had never happened. And I'm not being glib; one subject interrupts him to ask, "Who is this 'Mao' you keep talking about?"

As the chronicle unfolds, Porter pieces together a practice that anticipates the Buddha by four and half millennia. It's œcumenical and anticlerical, and often not Buddhist at all: about three quarters of the hermits Porter meets are Taoists. And it turns out that they are the ones obsessed with nontheism and koanic thought and oneness. Thus the oxymoron of Zen Buddhism: the "Zen" part, isn't Buddhist.

Porter puts his profession to work for the reader, bringing in Taoist texts little known in the West, and fleshing out a religion that is a great deal more than Lao Tzu. Nor does he despise eremitic discipline. One informant tells him you must mix Pure Land and Zen equally, or the imbalance will throw you off the Dharma. (Taoism strikes again.) Another says he neither meditates nor chants: "I just pass the time." "Trying to stay alive keeps me pretty busy," agrees a female hermit, then tosses in a statement that should be carved on every hermit's lintel: "Practice depends on the individual. This is my practice."

Not all of the hermits Porter finds live in deep seclusion. Some have built sparse "neighbourhoods" in the mountains, cabins scattered within shouting distance of one another, and some have formed sketes, small numbers of hermits living under one roof. They also recognise urban eremitical vocations. But most striking for me was their universal self-respect. "These are the [Zhongnan] Mountains," states one. "This is where monks and nuns come who are serious about their practice."

Published in 1993, the text has a slightly dated feel, owing to the use of old-style transliterations (i.e., Chungnan rather than Zhongnan). Its resemblance to Amongst White Clouds, Edward A. Burger's documentary on the same topic, is due to the fact that Burger took his inspiration from the Porter book. But where the film is necessarily summary, Porter takes full advantage of his literary medium to go deeper, investigate nuance, and pursue explanations. Where Burger implies, perhaps by oversight, that all Chinese hermits pledge to a teacher, Porter finds Buddhist Associations (parishes) that require no permission at all to sit in their jurisdiction. And as I speculated in my review of the Burger movie, Porter does indeed encounter Zhongnan hermits who reject the notion of separate religions entirely.

The book finishes on a note both hopeful and challenging, not just to China but to Buddhism the world over. Just before leaving the country, Porter happens upon what had for centuries been a thriving urban monastery. Long empty, the place has recently been occupied, in the Wall Street sense, by a knot of Zen hermits. They brook no hierarchy; they have no abbot. And though their new home is falling apart, they are in no rush to restore it; the decay keeps the tourists away.

And they've come to practise.

Topics:

Bill Porter,

book,

Buddha,

Buddhism,

China,

cœnobite,

Edward A. Burger,

hermit practice,

koan,

Lao Tzu,

monastery,

monk,

movie,

review,

Road to Heaven,

Taoism,

Zhongnan Mountains

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

WW: Crows on a wire

Wednesday, 19 September 2012

WW: Orb-weaving spider

Thursday, 13 September 2012

Hermitcraft: How to Make Ghee

I had never made ghee before I went to the mountain. In the planning stages of that project, having been raised on tales of people who starved eating rabbit, I believed I needed a source of dietary fat. (Wild rabbits have no fat, according to backwoods lore, hence you can die on a full stomach if you eat only that.) I'd heard about ghee for years, how versatile it was, how good it tasted, and how it kept for months without refrigeration. So that spring I put up four pints of the stuff, for use during my ango.

I had never made ghee before I went to the mountain. In the planning stages of that project, having been raised on tales of people who starved eating rabbit, I believed I needed a source of dietary fat. (Wild rabbits have no fat, according to backwoods lore, hence you can die on a full stomach if you eat only that.) I'd heard about ghee for years, how versatile it was, how good it tasted, and how it kept for months without refrigeration. So that spring I put up four pints of the stuff, for use during my ango.I found instructions on various Internet sites, but most or all of them were more complicated than necessary. Therefore, because ghee really is useful, especially for people who don't have refrigeration, I submit my recipe.

HOW TO MAKE GHEE

First, copy the following list of ingredients exactly and procure them from a licensed full-service grocer.

Full List of Ingredients:

1. Butter.

Next, melt the butter in a saucepan over medium heat. When liquefied, turn the temperature up to an active simmer. You're cooking off the water, which is in all butter, and so it will spit and carry on like any hot fat with water in it. DO NOT STIR. (Reason follows.)

You're also allowing the milk solids in the butter to congeal and sink to the bottom. This is the difference between ghee and drawn or clarified butter; many websites mistakenly equate the two. Ghee is cooked beyond simple separation, until all the water has steamed away and -- very important -- the milk solids have browned. This is what gives ghee its rich flavour, sometimes described as nutty, sweet, or lemony.

The only delicate part is telling when to take the pan off the heat, and that's only delicate because you have to do it by smell. First the ghee will go still; water gone, the bubbling stops. Not long after that, the kitchen will suddenly fill with a buttery scent some associate with baking croissants; to me, it's the smell of shortbread. It's a rich, sumptuous fragrance that takes no prisoners; you'll know it when it happens.

Tilt the pan gently at this point and note that the even layer of gunk on the bottom has a pastry-like, toast-brown aspect. That's your cue to take it off the heat.

Filter the ghee immediately, while still hot and thin. I use a paper coffee filter for this, for its fine mesh and ease of clean-up. (Woodstove Dharma strikes again.) You can also use muslin, cheesecloth, or a steel-screen coffee filter.

Pour the filtered ghee into a lidded jar or tub, and you're done.

Fact is, there are only two ways you can screw this up:

1. By becoming distracted (for example by drying paint, which is more exciting than watching butter melt) and allowing the milk solids on the bottom to burn rather than brown, giving the ghee an off flavour.

2. By boiling the ghee so vigorously that some slops on the stove and sets your house on fire, rendering flavour problems relatively moot by comparison.

The fix for both is the same: never leave the kitchen until the ghee is off the stove. I wipe down the counter, wash a few dishes, start another recipe, whatever I can do without stepping more than a metre away from the simmering pot. Adventure averted.

So, what kind of butter is best? Again, details are important: you must only use butter made from the milk of some animal. Do not attempt to make ghee from roofing tar, modelling clay, margarine, or old tires; the flavour will be disappointing.

Aside from that, any butter will do. Many websites insist the butter be unsalted; some insist it be expensive; some say it must be organic. The fact is, all butter works. On the Indian subcontinent, ghee is commonly made of yak butter, but the stores where I live tend to sell out of that before I get there, so I use cow butter. The sole difference between the salted and unsalted is purity: marginally-refined butter must be salted to stop all the solids that have been left in it going rancid. Unsalted butter must be more refined, to remove the spoil-prone proteins that would otherwise require salt, and this extra processing raises the price.

Because it has less by-catch to precipitate out, unsalted butter renders the most ghee per pound of butter. (Typically just a shade less than the original amount.) Good-quality salted butter renders slightly less ghee than that, but the ghee is not salty; the salt drops out with the rest of the solids. Even the cheapest, crappiest, scariest butter you can buy (that infamous single paper-wrapped rough-hewn slab that smells like cheese and tastes like salt paste) makes excellent ghee. There's just less of it. (Much less; you'll get about two thirds the original amount. In other words, a third of that machete butter, isn't butter.)

Ghee has less cholesterol than butter and keeps well without refrigeration if stored in a cool dark place. Since the crust left on the bottom of your pan is also what makes butter burn at high temperature, you can fry in ghee. And it can be used at the table like whole butter. The flavour is pleasant but subtle, and is compatible with most dishes.

Now that I'm initiated, I gotta have ghee. I fry potatoes in it, pop popcorn, and of course, sauté my masala. A pound or two put up, and I'm fixed for the year.

What was it they used to say on TV? "Try it, you'll like it."

Topics:

100 Days on the Mountain,

ango,

food,

hermitcraft,

India,

recipe

Wednesday, 12 September 2012

WW: Tugboat Holly Ann

Wednesday, 5 September 2012

WW: Bannock 'n' berries

Topics:

bread,

food,

hermitcraft,

salal,

summer,

tea,

wild edibles

Thursday, 30 August 2012

How to Save the World

The world does not need another activist.

The world does not need another defender.

The world does not need another patriot.

The world does not need another Buddhist.

The world needs calm, rational adults.

Please be one.

Topics:

clear-seeing,

ethics,

hermit practice,

kyôsaku,

mindfulness

Wednesday, 29 August 2012

WW: Okanogan farmhouse

Thursday, 23 August 2012

Sweetgrass Butte

As I swung around a blind bend the scene suddenly turned to Dante: an entire mountainside razed black and smouldering, heat waves dancing over its charred crust. I cranked the window against its acrid fumes and proceeded with caution. Yellow cards staked along the verge assured me this was a fire-management burn, under the theoretical control of a man behind a desk in a town twenty miles away. The Forest Service was getting a jump on wildfire season, burning the scrub and slash from this clearcut slope while the still-forested ones were fresh enough to discourage disaster.

As the road caterpillared around the next ridge, Hell vanished behind me and I was cutting diagonally across vertical green pastures, one after another, bands of deer and cattle, and the occasional integrated society of both, browsing amid the wildflowers. The grandeur and freedom so mesmerised me that I forgot my resolve to stay alert and deferred to the hood ornament again. By the time I came to my senses it was too late: I'd sleepwalked onto another summit feeder, trapped on a sharp, thin track jutting cloudward at something like the Ram's maximum grade. To the left, nothing but empty space; the mountain cut away so steeply from my outboard tires that it disappeared beneath them.

But with no hope of turning around, and nothing lying between me and the Swan Dive of Retribution, I had no choice but to push this steep and squirrelly road to its bitter end. I flattened the accelerator and the truck leapt gamely forward while I clung to the steering wheel and struggled to maintain maximum thrust on a sinuous ribbon of dirt. At that moment, momentum was survival; stop for any reason, and I wouldn't have the traction on that pitched surface to continue forward. And the thought of having to back all the way down that winding scaffold froze me in terror.

So heart in mouth, eyes riveted on the empty stratosphere, I Buck-Rogered that screaming Dodge into the cosmos. The g's pressed my spine into the bench while I fervently prayed I didn't cross another Forest Service truck bent on validating Einstein on the way down.

Time dwindles to a drip at such moments; for an instant, truth stands in bold relief. Hanging somewhere between an unremembered beginning and an unknowable end, possessed of a theoretical but functionally inoperative ability to stop, I could only rocket, as if a Saturn V were strapped to my backside, up and out. Welcome to existence.

At last the road crested, with nothing visible beyond but open sky. The Ram shot into it like a truck in a TV commercial, seeming to lift off the earth, and then lit soft as a cat on a freshly-graded plateau. I trod the brake and we sprayed to a stop. As the dust blew past the cab, I discovered the wherefore of this goat path to the stars: two huge, battleship-grey communication towers, their microwave drums implacably fixing the horizon, utterly indifferent to the panting insect at their feet. Red masthead lights winked in the linty clouds, warning jetliners not to ding their paint jobs on the bristling antennae.

I rested my forehead on the steering wheel and drew a long, shaky breath. The trouble you get into with your mind in neutral. According to the atlas, I had arrived at Sweetgrass Butte, official edge of the twentieth century, and at 1860 meters, the highest point in the region.

I lifted my hat, passed a hand through my hair. The truck purred underneath, as unperturbed as if we'd stopped at a traffic light. Apart from sky and cloud, and icy gusts bouncing the truck on its shocks like a basketball, we were alone; if not for those antennae, we might have touched down on some distant planet.

I reseated my hat, shifted mind and motor back into drive, and etched a tight doughnut in the gravel. By standing on the brake, I was able to shinny the truck back down that rope to the mainline. This time I could see the cliff dropping directly from the right front wheel, down and down, to a knife-edged Road Runner gully miles below. Where, the crease being forested, I wouldn't raise so much as a dust ring, should that tire wander a few inches west.

When at last I reached the bottom, I found that the intersection well-signed. I had no excuse for the detour, except possibly lack of sleep.

(Adapted from Rough Around the Edges, copyright RK Henderson. Photo courtesy of WikiMedia and a generous photographer.)

Wednesday, 22 August 2012

WW: Moonrise over sage hills

Thursday, 16 August 2012

Suicide: The Cause

(See also Suicide: The Cure.)

A former student of mine recently committed suicide. He was a truly exceptional young man, still in his college years, with a powerful soul that blazed a phosphorescent trail through his community and left a persistent retinal impression.

When I was a teacher there was much talk about suicide and how to prevent it. But I was amazed at the utter lack of insight into the core causes of suicide, and truly alarmed at the rank incompetence of official responses. Virtually all anti-suicide programmes for young people can be summed up by a poster I saw in a middle school counselling centre: a big yellow sun with a smiling cartoon character beneath, and the caption: "Life is beautiful! Don't throw it away!"

I wonder how many kids that poster killed.

For the record, people don't commit suicide because life sucks. They do it because people deny that life sucks. They're in pain, and everything they see and hear defines that as failure. Suicide is not an act of sadness or disillusionment; it's an act of loneliness and alienation.

The fact is, even concentrated individual treatment of suicidal persons is often embarrassingly nugatory. Know why? Because when it's over, we dump these unfashionably-perceptive people back into the same abusive, self-satisfied population that almost killed them in the first place.

So take a deep breath, brothers and sisters, because things are gonna get real.

It's not suicidal people who need treatment. It's you.

Your eternal War on Humans makes this life an unendurable hell. The practice of identifying humanity itself as weakness, and advancing shallow, half-baked ideologies, political, social, and religious, over decency, is deadly to human life.

When you brand someone a "felon" for life and deny her a job, a place to live, the vote, you fill this fishbowl with mustard gas. And it kills, liberally and indiscriminately. Because that's what mustard gas does.

When you meet poverty, sickness, and injustice with pat excuses, employ dehumanising rhetoric to smear their victims, preach and screech about this group and that group, value trophies over solutions and money over morality, you burn up all the oxygen in this Mason jar.

When you make an individual anathema, on any grounds, hold him up to ridicule, mock, bait, and blacklist him, you kill legions of faceless bystanders, though they be far removed from your victim-du-jour.

The suicide epidemic can't be addressed with the simplistic one-to-one arithmetic our plodding culture calls data. But whether or not the link can be easily demonstrated, every time you withhold basic dignity, respect, and forgiveness, you chop up the ties that connect us all. Fear and resentment and hopelessness drive the most human of us out of the herd, where they perish. And sometimes, every so often, what goes around comes home, and someone you love dies.

As for me, I wrote this world off a long time ago, and dedicated the remainder of my time here to transcending it. So today I am commemorating my brilliant young brother's life and death in accordance with my vows, by sitting sesshin on a small uninhabited island. In the course of this day I will perform acts of atonement, renew my commitment to the Dharma, and sit metta meditation for us all.

I'm inviting you personally to join me, by whatever path you walk. Please undertake the struggle to change your heart, and so change your species. Please find the courage to remain calm. Please abandon the wisdom of this world. Please cleave to truth.

And please stop being a mass-murderer.

A former student of mine recently committed suicide. He was a truly exceptional young man, still in his college years, with a powerful soul that blazed a phosphorescent trail through his community and left a persistent retinal impression.

When I was a teacher there was much talk about suicide and how to prevent it. But I was amazed at the utter lack of insight into the core causes of suicide, and truly alarmed at the rank incompetence of official responses. Virtually all anti-suicide programmes for young people can be summed up by a poster I saw in a middle school counselling centre: a big yellow sun with a smiling cartoon character beneath, and the caption: "Life is beautiful! Don't throw it away!"

I wonder how many kids that poster killed.

For the record, people don't commit suicide because life sucks. They do it because people deny that life sucks. They're in pain, and everything they see and hear defines that as failure. Suicide is not an act of sadness or disillusionment; it's an act of loneliness and alienation.

The fact is, even concentrated individual treatment of suicidal persons is often embarrassingly nugatory. Know why? Because when it's over, we dump these unfashionably-perceptive people back into the same abusive, self-satisfied population that almost killed them in the first place.

So take a deep breath, brothers and sisters, because things are gonna get real.

It's not suicidal people who need treatment. It's you.

Your eternal War on Humans makes this life an unendurable hell. The practice of identifying humanity itself as weakness, and advancing shallow, half-baked ideologies, political, social, and religious, over decency, is deadly to human life.

When you brand someone a "felon" for life and deny her a job, a place to live, the vote, you fill this fishbowl with mustard gas. And it kills, liberally and indiscriminately. Because that's what mustard gas does.

When you meet poverty, sickness, and injustice with pat excuses, employ dehumanising rhetoric to smear their victims, preach and screech about this group and that group, value trophies over solutions and money over morality, you burn up all the oxygen in this Mason jar.

When you make an individual anathema, on any grounds, hold him up to ridicule, mock, bait, and blacklist him, you kill legions of faceless bystanders, though they be far removed from your victim-du-jour.

The suicide epidemic can't be addressed with the simplistic one-to-one arithmetic our plodding culture calls data. But whether or not the link can be easily demonstrated, every time you withhold basic dignity, respect, and forgiveness, you chop up the ties that connect us all. Fear and resentment and hopelessness drive the most human of us out of the herd, where they perish. And sometimes, every so often, what goes around comes home, and someone you love dies.

As for me, I wrote this world off a long time ago, and dedicated the remainder of my time here to transcending it. So today I am commemorating my brilliant young brother's life and death in accordance with my vows, by sitting sesshin on a small uninhabited island. In the course of this day I will perform acts of atonement, renew my commitment to the Dharma, and sit metta meditation for us all.

I'm inviting you personally to join me, by whatever path you walk. Please undertake the struggle to change your heart, and so change your species. Please find the courage to remain calm. Please abandon the wisdom of this world. Please cleave to truth.

And please stop being a mass-murderer.

So here's to you, brave Uncle Francis

When the snowflakes fall, I will sing the blues

And when I think on how you left this world

I will remember how the world left you

Michael Marra

Topics:

alienation,

compassion,

death,

depression,

forgiveness,

hermit practice,

karma,

kyôsaku,

love,

meditation,

mindfulness,

possible,

suicide

Wednesday, 15 August 2012

WW: Paradise in the desert

Topics:

Columbia River,

Gold Side,

river,

summer,

Wordless Wednesday

Wednesday, 8 August 2012

WW: Western Skink

Topics:

Gold Side,

herpetology,

lizard,

wildlife,

Wordless Wednesday

Wednesday, 1 August 2012

WW: Jumping Cactus

Thursday, 26 July 2012

Street Level Zen: Karma

Wednesday, 25 July 2012

WW: Skipjack

(Vessels of this type are traditional on the Cheseapeake and surrounding waterways, but rare on Puget Sound. Not sure why, since the sailing grounds are similar. In any case, it's nice to glimpse this one's lovely lines in the bay.)

Thursday, 19 July 2012

Hermitcraft: Bottle Traps

This one isn't about practice or practicalities. It's about fun. Sue me.

This one isn't about practice or practicalities. It's about fun. Sue me.It's high summer here in the planet's attic, and the kids are out of school. Most pursuits this time of year involve aquatic habitats of one kind or another. So here's a simple little project that costs nothing and pays off big in educational entertainment for all ages. NOTE: These traps are also often used on dry land to catch lizards. If you use one for this, make double sure to check it frequently and keep it out of the sun at all times. Failing this can result in a truly horrific death for an unoffending creature.

These survey traps are made from a pair of 2-litre soda bottles, and not much else. And they really work. There are YouTube tutorials galore on the subject; a "bottle trap" search there will net (get it? [Fish]-net? [Inter]-net?) a hundred vids. But I've yet to find a design as refined as my own, so I'm sharing it. (By way of credentials: I'm an old aquarist, specialising in local habitats. At one point, when I was twelve, I had six aquariums, fresh and salt, bubbling away in my bedroom.)

The massage:

1. Remove the labels from two clean 2-litre soda bottles. They can be round New World bottles or square Old World ones. Clear plastic works best; others will also do.

2. Cut the bottom off one, neatly and carefully. Scissors work best, after making a small starting slit with a knife. Discard the bottom, or keep it for studying collected specimens and infusoria. (Very handy.)

3. Cut both the bottom and the top off the second bottle. Set aside or discard the bottom.

4. Cut a 1-inch vertical slit in one edge of the dismembered body of the second bottle.

5. Now lengthen the barrel of your trap by grafting this onto the bottomless first bottle. (Note the two-toned example in the photo.) Finesse the slitted end into the opening where the first bottle's bottom used to be, and wedge it tight and straight. You should get an overlap of about three quarters of an inch.

6. Invert the second bottle's cut-off top in the open end of the trap to form a funnel-shaped head, as shown in the photos. Remember to take the cap off first! (Autobiographical.)

7. Fasten the pieces together. The easiest and most elegant way to do this is with a pencil-tipped solder iron. Heat it up well and push the tip gently through the plastic, all along both seams. Don't rush; savour the sizzle. This typically rivets the pieces together even as it perforates them.

If you haven't got a solder iron, next best thing is a heated welding rod or similar metal, followed by a hole-punch, either for paper or leather. After that is a very sharp drill. In any case, cold holes need to be bound together; use string, twist-ties, brads, or nylon zip ties. (This actually makes a more versatile trap, because you can unmount the head to put in certain baits or remove an overlarge catch.)

You can also use a common desktop stapler on the head; a deep-throated pamphlet stapler will fasten the whole trap.

8. Perforate the trap all over, from about three inches below the head seam to about three inches short of the exhaust funnel shoulder. This helps it sink and drain readily and allows prey to smell the bait. (The upper no-hole zone is so you don't perforate the head funnel; the lower one conserves a pint of water in the exhaust funnel when you haul your trap. This greatly reduces injury to life forms, makes them easier to identify and admire, and facilitates removal.) Again, a solder iron makes the neatest and easiest holes.

To set, make a bridle by tying eight-inch strings to four evenly-spaced holes in the head seam and knotting their free ends together. Then tie a long string to the knot. Drop some bait in the barrel, mind the line, and heave the trap overboard.

If you're fishing from the bank or off a dock, you can tie the line off there; the richest pickings are in that zone, anyway. Away from shore, hang a small buoy, such as a stick, cork, fishing bobber, or small plastic bottle, on the bitter end of the trap line and bend on an external anchor, such as a brick or horseshoe, near the head. All sets must be securely belayed to structure or an anchor at all times, regardless of location.

Leave the set unmolested for several hours; overnight is best. To evacuate the catch, hold the drained trap vertically over the water or collecting bucket and unscrew the exhaust cap.

Good starter baits include bread, cheese, cat food, liver, lunch meat, tuna fish, fish parts, clam necks, cocktail shrimp, and corn. Note: it's all about the bait. One won't catch a cold; another will fill the trap. And when seasons, locations, or depths change, it's back to square one.

Survey traps such as these could serve a limited survival end, by supplying bait, or a few crawdads for food. Or they might catch fry that will tell you what to tie on to hook a real meal. Aside from that they're seriously useful in monitoring the health of a waterway (such as the lake I grew up on, which is now mostly dead from overdevelopment and repeated herbicide attacks). Set out a raft of them, vary the parameters over time, and keep careful records. Such hard data can make the difference in a bid to change local law and policy.

Or… just make some kid's day. Ever seen a four-year-old jump up and down over a sculpin in a bottle trap? If Nintendo only knew, they'd make 'em illegal.

Thumbnail-sized rock bass caught this

summer in one of these traps

Topics:

beach,

crayfish,

fish,

hermitcraft,

lake,

lizard,

Puget Sound,

river,

summer,

wildlife

Wednesday, 18 July 2012

WW: Pelicans

Monday, 16 July 2012

Birds Know It

Thursday, 12 July 2012

Ancestor Path Kyôsaku

no forests, no deadfall;

no deadfall, no firewood;

no firewood, no tea;

no tea, no meditation;

no meditation, no hermits.

Bill Porter, in Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits.

(Review here.)

Topics:

Bill Porter,

hermit practice,

kyôsaku,

meditation,

poem,

Road to Heaven,

tea,

Zhongnan Mountains

Wednesday, 11 July 2012

Thursday, 5 July 2012

Hermitcraft: Candles

A few months ago I posted instructions for making your official Hermit Club rushlight, or candle lantern. That left you with a cheap, serviceable product that did not, however, throw any light, because I didn't explain how to make the candles that go inside. Today, I caulk that seam.

A few months ago I posted instructions for making your official Hermit Club rushlight, or candle lantern. That left you with a cheap, serviceable product that did not, however, throw any light, because I didn't explain how to make the candles that go inside. Today, I caulk that seam.Chandlery is a complex art, demanding skill, experience, and money. Which is why I'm not sure this counts, because these candles are cheap, easy, and homely. (Bindle technology strikes again.) But they fit perfectly in a tin-can rushlight, and properly made, burn for about a month of sitting.

You will need:

Candle wax.

A large tin can.

A sauce pan.

A stove.

Boiling water.

An empty cardboard frozen orange juice can, the kind with metal ends.

Cotton wicking.

A hammer and a small nail.

Duck tape. (It is too duck tape. Don't tape ducts with it; you'll be fined back to the Stone Age.)

Two square sticks and a rubber band.

I find much of my wax on the beach (see photo, right); the fishing fleet uses it for something. The rest comes from dripping and remnants of previous candles, and recycled candles-of-fortune.

I find much of my wax on the beach (see photo, right); the fishing fleet uses it for something. The rest comes from dripping and remnants of previous candles, and recycled candles-of-fortune. I don't care about colour, except I never melt green and red wax together, because the brownish-grey they become is literally nauseating. Also, the more colour in the pot, the lower and slower the candles will burn. (The colorant isn't inflammable.) So you will have to soften over-coloured wax by stirring in lamp oil – after taking the pot off the heat, of course. For the same reason, it's a good idea to whittle the "rind" off recyclable candles that are coloured only on the outside, before melting; that shell is pure colorant, and of no use to us.

For wicks you can buy the dedicated product from a craft store, or use heavy cotton butcher's twine right off the spool, or braid that ubiquitous small white cotton "kite string" parcel twine to the proper gauge. (My favourite option, because you can adjust the size by adding or subtracting strands. Plus it's cheap.)

The procedure:

1. Put chunks of wax in the tin can, place the can in the sauce pan, and fill the pan with boiling water to just shy of the point where the can would float.

2. Place the sauce pan over medium-low heat and keep an eye on it. Paraffin wax becomes paraffin paraffin when it melts. (That's kerosene to my American friends.) In other words, you're simmering a pan of lamp oil on your stove. You don't want it boiling, sloshing on the burner, or copping any kind of attitude.

3. While you're waiting for the wax to melt, poke a hole dead-centre of the juice can's metal bottom, using the hammer and nail. The hole should be just big enough to admit the wick; any larger, and leaks become an issue. Also, cut the juice can down about an inch and a half for optimum rushlight size. (For generic pillar candles, you can use the can uncut.)

3. While you're waiting for the wax to melt, poke a hole dead-centre of the juice can's metal bottom, using the hammer and nail. The hole should be just big enough to admit the wick; any larger, and leaks become an issue. Also, cut the juice can down about an inch and a half for optimum rushlight size. (For generic pillar candles, you can use the can uncut.)4. Knot one end of the wicking, trim the knot close, and thread the string up through the hole. You may need to dip the unknotted end in wax first, to make it stiff. Cut the wicking off two or three inches longer than the final wick will be.

5. Duck tape the end very securely, because that stuff isn't even almost heat-proof. (See? Completely unusable for ductwork.) Use two strips, crossed and running halfway up the sides of the can, and burnish them down well all over the bottom and around the knot.

6. Rubber-band the two square sticks together at one end to make an elastic clamp. Pass the wick between its "jaws" and tighten it up so the wick remains secure and plumb in the mould. (Not enough tension and the wick will meander while the wax cools, causing the candle to perform poorly.)

7. Pour about an inch of wax in the bottom of the mould and let it cool for a few minutes. This helps prevent leaking from the wick hole. When the wax has thickened a little, fill up the mould and take the pan and melting can off the heat. Allow the candle to cool completely at room temperature, about three hours.

7. Pour about an inch of wax in the bottom of the mould and let it cool for a few minutes. This helps prevent leaking from the wick hole. When the wax has thickened a little, fill up the mould and take the pan and melting can off the heat. Allow the candle to cool completely at room temperature, about three hours.8. Because paraffin wax contracts as it solidifies, you will find a deep depression in the top of the cooled candle. Re-melt the remaining wax and fill it level again. When the topping-up has hardened, you can scrape off the knot with a sharp knife and pull the candle out by the wick. If it sticks, just tear away the cardboard.

If you find that your homemade candle consistently drowns (the flame burns very low, or goes out entirely), then your wick may not be big enough. (Give it a few chances; for some reason, performance can vary from sitting to sitting.) If it burns too high and threatens to burst the wax pool, the wick may need trimming. If that doesn't fix it, it's too big.

In either case, the solution is to melt the candle back down and mould another with a better wick. As the blend in your melting can changes, due to variations in the pigment content and hardness of added wax, you may need to adjust the gauge of your wicks. With time you'll develop a sixth sense for these things and seldom have to resort to repouring.

And there you are. A cheap candle, perfectly sized for your rushlight.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)