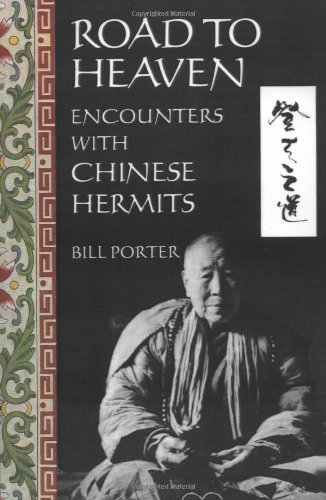

In Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits, Bill Porter writes:

"Throughout Chinese history, there have always been people who preferred to spend their lives in the mountains, getting by on less, sleeping under thatch, wearing old clothes, working the higher slopes, not talking much, writing even less - maybe a few poems, a recipe or two. Out of touch with the times but not with the seasons, they cultivated roots of the spirit, trading flatland dust for mountain mist."

He ends with a declaration: "Distant and insignificant, they were the most respected men and women in the world's oldest society."

Road to Heaven is the memoir of Porter's 1989 hunt for Buddhism in the People's Republic of China. Theorising that in order to survive Mao's earth-scorching Cultural Revolution, any true practice would have had to return to its ancestral source, he spurned monasteries and struck out for the badlands. Which is already intriguing: an ordained cœnobite and authority on Buddhist scripture, with sixteen published translations to his name (and his ordination name, Red Pine), who respects hermit monks.

His journey starts at the toe of the Zhongnan Mountains, China's vast, rugged outdoor monastery, where Porter and a photographer friend drop by every ancient religious site he can find in the texts. It's depressing: landmark after landmark razed to the ground, or turned to profane ends by the Red Guards; books burned, practice banned, monks killed. There are still clerics around, but they live more like bureaucrats than monks. And they assure Porter that "nowadays, all monks live in temples." (I guess some wars are truly global.)

But Porter persists. Armed with fluent language skills, he follows a trail of hearsay off the pavement, and then off the road, and finally, in one instance, up a long chain bolted to a cliff. (Incredibly, he's given run of the Red Chinese outback, though The Man does contribute a few scary moments.) And up there, on the howling peaks where they've been for seven thousand years, he finds a whole flagrant hermit nation, pounding their ancient path as if the 20th century had never happened. And I'm not being glib; one subject interrupts him to ask, "Who is this 'Mao' you keep talking about?"

As the chronicle unfolds, Porter pieces together a practice that anticipates the Buddha by four and half millennia. It's œcumenical and anticlerical, and often not Buddhist at all: about three quarters of the hermits Porter meets are Taoists. And it turns out that they are the ones obsessed with nontheism and koanic thought and oneness. Thus the oxymoron of Zen Buddhism: the "Zen" part, isn't Buddhist.

Porter puts his profession to work for the reader, bringing in Taoist texts little known in the West, and fleshing out a religion that is a great deal more than Lao Tzu. Nor does he despise eremitic discipline. One informant tells him you must mix Pure Land and Zen equally, or the imbalance will throw you off the Dharma. (Taoism strikes again.) Another says he neither meditates nor chants: "I just pass the time." "Trying to stay alive keeps me pretty busy," agrees a female hermit, then tosses in a statement that should be carved on every hermit's lintel: "Practice depends on the individual. This is my practice."

Not all of the hermits Porter finds live in deep seclusion. Some have built sparse "neighbourhoods" in the mountains, cabins scattered within shouting distance of one another, and some have formed sketes, small numbers of hermits living under one roof. They also recognise urban eremitical vocations. But most striking for me was their universal self-respect. "These are the [Zhongnan] Mountains," states one. "This is where monks and nuns come who are serious about their practice."

Published in 1993, the text has a slightly dated feel, owing to the use of old-style transliterations (i.e., Chungnan rather than Zhongnan). Its resemblance to Amongst White Clouds, Edward A. Burger's documentary on the same topic, is due to the fact that Burger took his inspiration from the Porter book. But where the film is necessarily summary, Porter takes full advantage of his literary medium to go deeper, investigate nuance, and pursue explanations. Where Burger implies, perhaps by oversight, that all Chinese hermits pledge to a teacher, Porter finds Buddhist Associations (parishes) that require no permission at all to sit in their jurisdiction. And as I speculated in my review of the Burger movie, Porter does indeed encounter Zhongnan hermits who reject the notion of separate religions entirely.

The book finishes on a note both hopeful and challenging, not just to China but to Buddhism the world over. Just before leaving the country, Porter happens upon what had for centuries been a thriving urban monastery. Long empty, the place has recently been occupied, in the Wall Street sense, by a knot of Zen hermits. They brook no hierarchy; they have no abbot. And though their new home is falling apart, they are in no rush to restore it; the decay keeps the tourists away.

And they've come to practise.

Thursday, 27 September 2012

Good Book: Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits

Topics:

Bill Porter,

book,

Buddha,

Buddhism,

China,

cœnobite,

Edward A. Burger,

hermit practice,

koan,

Lao Tzu,

monastery,

monk,

movie,

review,

Road to Heaven,

Taoism,

Zhongnan Mountains

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

WW: Crows on a wire

Wednesday, 19 September 2012

WW: Orb-weaving spider

Thursday, 13 September 2012

Hermitcraft: How to Make Ghee

I had never made ghee before I went to the mountain. In the planning stages of that project, having been raised on tales of people who starved eating rabbit, I believed I needed a source of dietary fat. (Wild rabbits have no fat, according to backwoods lore, hence you can die on a full stomach if you eat only that.) I'd heard about ghee for years, how versatile it was, how good it tasted, and how it kept for months without refrigeration. So that spring I put up four pints of the stuff, for use during my ango.

I had never made ghee before I went to the mountain. In the planning stages of that project, having been raised on tales of people who starved eating rabbit, I believed I needed a source of dietary fat. (Wild rabbits have no fat, according to backwoods lore, hence you can die on a full stomach if you eat only that.) I'd heard about ghee for years, how versatile it was, how good it tasted, and how it kept for months without refrigeration. So that spring I put up four pints of the stuff, for use during my ango.I found instructions on various Internet sites, but most or all of them were more complicated than necessary. Therefore, because ghee really is useful, especially for people who don't have refrigeration, I submit my recipe.

HOW TO MAKE GHEE

First, copy the following list of ingredients exactly and procure them from a licensed full-service grocer.

Full List of Ingredients:

1. Butter.

Next, melt the butter in a saucepan over medium heat. When liquefied, turn the temperature up to an active simmer. You're cooking off the water, which is in all butter, and so it will spit and carry on like any hot fat with water in it. DO NOT STIR. (Reason follows.)

You're also allowing the milk solids in the butter to congeal and sink to the bottom. This is the difference between ghee and drawn or clarified butter; many websites mistakenly equate the two. Ghee is cooked beyond simple separation, until all the water has steamed away and -- very important -- the milk solids have browned. This is what gives ghee its rich flavour, sometimes described as nutty, sweet, or lemony.

The only delicate part is telling when to take the pan off the heat, and that's only delicate because you have to do it by smell. First the ghee will go still; water gone, the bubbling stops. Not long after that, the kitchen will suddenly fill with a buttery scent some associate with baking croissants; to me, it's the smell of shortbread. It's a rich, sumptuous fragrance that takes no prisoners; you'll know it when it happens.

Tilt the pan gently at this point and note that the even layer of gunk on the bottom has a pastry-like, toast-brown aspect. That's your cue to take it off the heat.

Filter the ghee immediately, while still hot and thin. I use a paper coffee filter for this, for its fine mesh and ease of clean-up. (Woodstove Dharma strikes again.) You can also use muslin, cheesecloth, or a steel-screen coffee filter.

Pour the filtered ghee into a lidded jar or tub, and you're done.

Fact is, there are only two ways you can screw this up:

1. By becoming distracted (for example by drying paint, which is more exciting than watching butter melt) and allowing the milk solids on the bottom to burn rather than brown, giving the ghee an off flavour.

2. By boiling the ghee so vigorously that some slops on the stove and sets your house on fire, rendering flavour problems relatively moot by comparison.

The fix for both is the same: never leave the kitchen until the ghee is off the stove. I wipe down the counter, wash a few dishes, start another recipe, whatever I can do without stepping more than a metre away from the simmering pot. Adventure averted.

So, what kind of butter is best? Again, details are important: you must only use butter made from the milk of some animal. Do not attempt to make ghee from roofing tar, modelling clay, margarine, or old tires; the flavour will be disappointing.

Aside from that, any butter will do. Many websites insist the butter be unsalted; some insist it be expensive; some say it must be organic. The fact is, all butter works. On the Indian subcontinent, ghee is commonly made of yak butter, but the stores where I live tend to sell out of that before I get there, so I use cow butter. The sole difference between the salted and unsalted is purity: marginally-refined butter must be salted to stop all the solids that have been left in it going rancid. Unsalted butter must be more refined, to remove the spoil-prone proteins that would otherwise require salt, and this extra processing raises the price.

Because it has less by-catch to precipitate out, unsalted butter renders the most ghee per pound of butter. (Typically just a shade less than the original amount.) Good-quality salted butter renders slightly less ghee than that, but the ghee is not salty; the salt drops out with the rest of the solids. Even the cheapest, crappiest, scariest butter you can buy (that infamous single paper-wrapped rough-hewn slab that smells like cheese and tastes like salt paste) makes excellent ghee. There's just less of it. (Much less; you'll get about two thirds the original amount. In other words, a third of that machete butter, isn't butter.)

Ghee has less cholesterol than butter and keeps well without refrigeration if stored in a cool dark place. Since the crust left on the bottom of your pan is also what makes butter burn at high temperature, you can fry in ghee. And it can be used at the table like whole butter. The flavour is pleasant but subtle, and is compatible with most dishes.

Now that I'm initiated, I gotta have ghee. I fry potatoes in it, pop popcorn, and of course, sauté my masala. A pound or two put up, and I'm fixed for the year.

What was it they used to say on TV? "Try it, you'll like it."

Topics:

100 Days on the Mountain,

ango,

food,

hermitcraft,

India,

recipe

Wednesday, 12 September 2012

WW: Tugboat Holly Ann

Wednesday, 5 September 2012

WW: Bannock 'n' berries

Topics:

bread,

food,

hermitcraft,

salal,

summer,

tea,

wild edibles

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)