By oneself is evil done

By oneself is one defiled

By oneself is evil left undone

By oneself is one made pure

Purity and impurity depend on oneself

No one can purify another

Siddhartha Gautama, Dhammapada XII, verse 165.

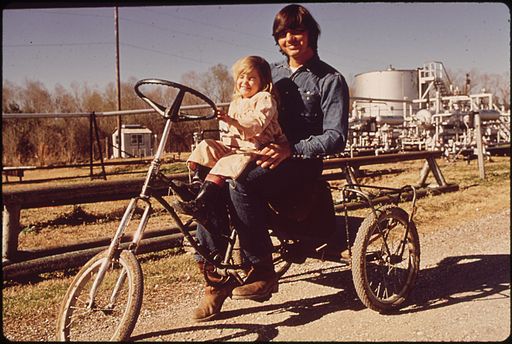

(Photo of a Buddha from the Yungang Grottoes courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)