Thursday, 31 December 2015

Forgiveness

This summary is not available. Please

click here to view the post.

Wednesday, 30 December 2015

Thursday, 24 December 2015

Wednesday, 23 December 2015

Thursday, 17 December 2015

Hermitcraft: Trailer Park Samosas

Just in time for holiday entertaining, here's a killer recipe for an easy, addictive appetiser or side dish. Both the "Quick" and "Better" versions can be filled with either hamburger or lentils, suitable for omnivore and vegetarian alike, and the ingredients are readily available from most any North American supermarket. The "Quick" recipe is indeed quick: about half an hour from groceries to piping hot, fragrant samosas. The "Better" one takes a little longer, but is well worth the extra time if you've got it. (Note: both are also fairly spicy; for milder results, dial back or omit the jalapeños.)

Just in time for holiday entertaining, here's a killer recipe for an easy, addictive appetiser or side dish. Both the "Quick" and "Better" versions can be filled with either hamburger or lentils, suitable for omnivore and vegetarian alike, and the ingredients are readily available from most any North American supermarket. The "Quick" recipe is indeed quick: about half an hour from groceries to piping hot, fragrant samosas. The "Better" one takes a little longer, but is well worth the extra time if you've got it. (Note: both are also fairly spicy; for milder results, dial back or omit the jalapeños.)Pastry for both versions:

2 tubes ready-bake crescent roll dough, for 16 rolls in all. Keep tubes chilled until the moment of use.

"Quick" filling:

1 tablespoon ghee or cooking oil

1/2 teaspoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon minced onion

1 1/2 teaspoons jarred jalapeños, minced

a few good grinds of fresh black pepper

2 teaspoons prepared curry powder

pinch each ground cinnamon and cloves (just a pinch; you shouldn't taste either in the finished product)

1/2 teaspoon powdered ginger

1/2 teaspoon chili powder

1/2 cup diced tomatoes

1/4 teaspoon thyme

1 tablespoon minced celery

1 pound very lean ground beef, or cooked lentils (about 1/2 cup raw)

"Better" filling:

1 tablespoon ghee or cooking oil

1 inch grated gingerroot

|

| "Better" spice mix; beef or lentils will be stirred into this |

1 tablespoon minced onion

1 1/2 teaspoons jarred jalapeños, minced

a few good grinds of fresh ground black pepper

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1/4 teaspoon turmeric

good pinch garam masala, if available

1/2 teaspoon coriander powder

pinch each ground cinnamon and cloves (just a pinch; you shouldn't taste either in the finished samosas)

1/2 teaspoon chili powder

1/2 cup diced tomatoes

1/4 teaspoon thyme

1 tablespoon minced celery

1 pound very lean ground beef, or cooked lentils (about 1/2 cup raw)

Instructions for both (all four?) filling recipes:

Preheat oven to 375F.

Warm ghee or oil in a heavy skillet over medium-low heat. Add all ingredients up to tomatoes, in order, and simmer gently until onion is translucent and spices are fragrant. Add tomatoes, thyme, and celery, raise heat slightly, and cook until celery is soft and mixture is pasty, scraping it frequently about with a spatula.

Add beef or lentils, mix thoroughly with spice mixture, and simmer until beef is browned or lentils have thickened, about 10 minutes. Scrape frequently with the edge of a spatula; if the mixture gets too dry, add a little water .

To make samosas:

Unroll crescent roll dough and separate into triangles.

Put a heaping tablespoon of filling in the centre of the wide end of each triangle. Pull up the short corners and seal them together on top of the filling; pull the long last corner over the top of the sealed short ones and around the back to form a round, filled pastry; pinch and seal all seams closed so that no filling shows. Place on an ungreased cookie sheet.

Bake at 375°F for 10 minutes or until golden brown. (Take care they don't burn; these bake very quickly.) Serve warm, wrapped in a tea towel, as finger food.

Wednesday, 16 December 2015

WW: Gift of my own blackberry wine

(I used to make blackberry wine every year, an activity I dearly loved. Sadly, life conspired to make the 2008 vintage my last. Last week I was rooting deep in a forgotten storage corner and came up with this: my last-ever bottle, which somehow escaped consumption.

But not for long. Brilliant Christmas gift.)

But not for long. Brilliant Christmas gift.)

Topics:

Christmas,

hermitcraft,

wild edibles,

wine,

Wordless Wednesday

Thursday, 10 December 2015

Sound of the Season

Twelfth Month singers

seven feet away

a little one sings

Issa

(1880 American Christmas card courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

seven feet away

a little one sings

Issa

(1880 American Christmas card courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Wednesday, 9 December 2015

Thursday, 3 December 2015

The Three Infinitudes

The length of time.

The depth of space.

The ignorance of people.

(Photo of one tiny chunk of space, containing over 200 galaxies [that's galaxies, brothers and sisters: each an aggregation of billions of stars, most of those presumably anchoring entire solar systems] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, NASA, and the Hubble Telescope.)

Wednesday, 2 December 2015

Thursday, 26 November 2015

Good Book: Meditation in the Wild

In Meditation in the Wild: Buddhism's Origin in the Heart of Nature, Charles S. Fisher writes:

Not that it's easy; as a quotation from Theravada scholar Richard Gombrich points out:

But outdoor practice was hard – even harder than it is now – with dangerous wildlife and tribal warriors still ruling the outback, and the impulse to organise was strong. Yet The Kindred Sayings of Kassapa show the Buddha "bemoan[ing] the passing of the forest way of life and criticis[ing] those who depart from it"; he may have gone so far as to advocate a straight-up return to hunter-gathering, according to texts that describe his sangha living off the land, hunting game, and never returning to the Red Dust World. The fact that Buddhism spread to new lands precisely as Indian forests were clearcut leads one to wonder what exactly the motivations of those first "missionaries" were. (It also throws intriguing light on the Bodhidharma story. Canon holds that when asked why he came all the way to China to sit under a tree, he replied: "Because this is the best tree in the world." Perhaps his actual words were something like, "Because you still have trees.")

Conjecture aside, the founding generation of Buddhists exhorted aspirants to imitate Gautama literally. Mahakasyapa, a member of the Buddha's inner circle, died a loud and proud hermit, as did no less than Sariputra, of Heart Sutra fame. Finally, reports of early Western observers – Greek travellers – confirm that the first Buddhists were itinerants, without clergy or temples.

But as the movement grew respectable and sedentary, hermits were increasingly viewed as "unsocial, possibly antisocial, and potentially dangerous to established Buddhism." This last repeated pious tales of the Buddha's forest practice, but openly discouraged others from emulating it. Old-school monks, known as "mahallas", were accused of backsliding and dissolution and reviled by the ordained. (Some verses quoted in Wild are stunningly similar to the rant St. Benedict unleashed on Sarabaites and Gyrovagues at an identical stage in Christian history.)

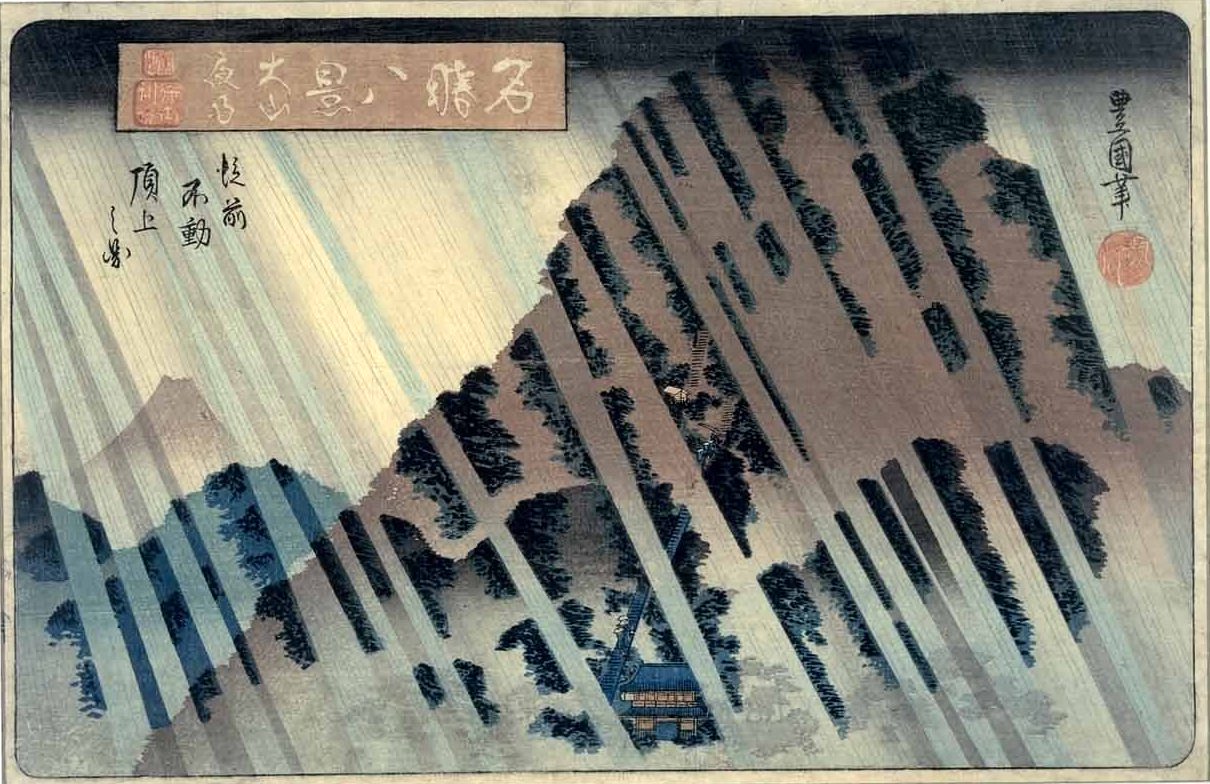

To be sure, over the past 2500 years Buddhist back-to-the-landers have continued to crop up; modern Zen and Theravada are remnants of two such rebellions. Possibly Wild's greatest gift is the two and half millennia of these forgotten reformers it lifts from obscurity. Along the way its author weighs the relative merit of individual cases. He reviews Issa's suburban eremiticism, which echoes most current hermit practices, with guarded approval, but – interestingly – takes Bashō, Ryokan, and Kamo No Chomei firmly to the woodshed.

And that's where I get off the train. In these passages, Fisher reminds me of Thoreau's critics, calling down suspects for claims they never made. His indictment of Bashō does ring, but he repeatedly spins individual innovation in self-directed practices as weak or duplicitous; in the case of Ikkyu, he indulges in crass bourgeois morality. Somehow, in all of his research on us, he missed our core vow: "I will neither take nor give orders." I may raise an eyebrow at others (OK: I do raise an eyebrow at others) but ultimately I have no right to deplore them. Licence to judge is a delusion of the ordained.

But this mild annoyance in no way diminishes the significance of Fisher's work. His journalism is both intrepid and thorough, penetrating the Thai forest lineage – a modern restoration movement – at length and documenting the gradual deterioration of Zen, from Bodhidharma's boldly-planted hermit flag, to the dismissal of 19th century hermit Ryokan (his own beefs with him aside) as a "lunatic". He finishes with an account of his own brushes with eremitical practice (Fisher is not a practising hermit per se, but is attracted to our forms) and a light survey of four contemporary American hermits. All in all, it's the most comprehensive treatment of the subject I've found anywhere.

And I found it impossible to put down. With any luck, Meditation in the Wild will stand for many years as Eremitical Buddhism 101 for sincere students of the Buddha's way.

"Buddhism was born in the forests of India. [...] The Buddha found his original revelation while practicing as a forest monk. [...] He developed an understanding of nature which would become part of the remedy he proposed for the problem of human discontent. [...] He chose wild nature - the evolutionary context in which humans arose - as the place to do this. [...] He went to the place in the human mind where there is understanding without words."The next 315 pages go on to prove his thesis.

Not that it's easy; as a quotation from Theravada scholar Richard Gombrich points out:

"So much of the material attributed to [the Buddha]… is so obviously inauthentic that we can suspect almost everything. In fact, it seems impossible to establish what the Buddha really taught. We can only know what early Buddhists believed he taught."And this, as it happens, is very different from what we've been told. For example, some of their records maintain that Gautama encountered his famous Four Sights on the way to the forest, where he sat and pondered what he saw. Others suggest that the pivotal debate between Mara and Gautama on the eve of his Enlightenment was actually about the Devil's contention that the young man had no right to strive to end suffering. All those statues of him touching the earth, they contend, depict him saying, "Check it out, dipstick: I'm home. Go find someone who cares."

But outdoor practice was hard – even harder than it is now – with dangerous wildlife and tribal warriors still ruling the outback, and the impulse to organise was strong. Yet The Kindred Sayings of Kassapa show the Buddha "bemoan[ing] the passing of the forest way of life and criticis[ing] those who depart from it"; he may have gone so far as to advocate a straight-up return to hunter-gathering, according to texts that describe his sangha living off the land, hunting game, and never returning to the Red Dust World. The fact that Buddhism spread to new lands precisely as Indian forests were clearcut leads one to wonder what exactly the motivations of those first "missionaries" were. (It also throws intriguing light on the Bodhidharma story. Canon holds that when asked why he came all the way to China to sit under a tree, he replied: "Because this is the best tree in the world." Perhaps his actual words were something like, "Because you still have trees.")

Conjecture aside, the founding generation of Buddhists exhorted aspirants to imitate Gautama literally. Mahakasyapa, a member of the Buddha's inner circle, died a loud and proud hermit, as did no less than Sariputra, of Heart Sutra fame. Finally, reports of early Western observers – Greek travellers – confirm that the first Buddhists were itinerants, without clergy or temples.

But as the movement grew respectable and sedentary, hermits were increasingly viewed as "unsocial, possibly antisocial, and potentially dangerous to established Buddhism." This last repeated pious tales of the Buddha's forest practice, but openly discouraged others from emulating it. Old-school monks, known as "mahallas", were accused of backsliding and dissolution and reviled by the ordained. (Some verses quoted in Wild are stunningly similar to the rant St. Benedict unleashed on Sarabaites and Gyrovagues at an identical stage in Christian history.)

To be sure, over the past 2500 years Buddhist back-to-the-landers have continued to crop up; modern Zen and Theravada are remnants of two such rebellions. Possibly Wild's greatest gift is the two and half millennia of these forgotten reformers it lifts from obscurity. Along the way its author weighs the relative merit of individual cases. He reviews Issa's suburban eremiticism, which echoes most current hermit practices, with guarded approval, but – interestingly – takes Bashō, Ryokan, and Kamo No Chomei firmly to the woodshed.

And that's where I get off the train. In these passages, Fisher reminds me of Thoreau's critics, calling down suspects for claims they never made. His indictment of Bashō does ring, but he repeatedly spins individual innovation in self-directed practices as weak or duplicitous; in the case of Ikkyu, he indulges in crass bourgeois morality. Somehow, in all of his research on us, he missed our core vow: "I will neither take nor give orders." I may raise an eyebrow at others (OK: I do raise an eyebrow at others) but ultimately I have no right to deplore them. Licence to judge is a delusion of the ordained.

But this mild annoyance in no way diminishes the significance of Fisher's work. His journalism is both intrepid and thorough, penetrating the Thai forest lineage – a modern restoration movement – at length and documenting the gradual deterioration of Zen, from Bodhidharma's boldly-planted hermit flag, to the dismissal of 19th century hermit Ryokan (his own beefs with him aside) as a "lunatic". He finishes with an account of his own brushes with eremitical practice (Fisher is not a practising hermit per se, but is attracted to our forms) and a light survey of four contemporary American hermits. All in all, it's the most comprehensive treatment of the subject I've found anywhere.

And I found it impossible to put down. With any luck, Meditation in the Wild will stand for many years as Eremitical Buddhism 101 for sincere students of the Buddha's way.

Topics:

Bashō,

Bodhidharma,

book,

Buddha,

Buddhism,

Charles S. Fisher,

China,

Christianity,

hermit practice,

Ikkyu,

India,

Issa,

Kamo no Chômei,

meditation,

Meditation in the Wild,

review,

Ryokan,

St. Benedict,

Theravada,

Zen

Wednesday, 25 November 2015

WW: 1812 veteran

(I recently had to correct the Wikipedia entry for George Bush, earliest American settler in the Olympia area, which identified him as "the only 1812 veteran buried in Thurston County". Meet William Rutledge, friend and [still] neighbour of Bush, who arrived soon after. He lies about 10 feet away in the same pioneer graveyard, beneath a memorial placed by the N.S.U.S.D. 1812. [Interestingly, they did not afix such a plaque on Bush's stone, which is still the barely-legible 1863 original.])

Thursday, 19 November 2015

Good Song: Nowhere Else But Here

Here's one for those days. You know the ones. The grim, sparks-fly-upward days. There's much to love about this quintessentially Australian song. You just can't listen to the Pigrim Brothers' vocals and instrumentals and not become equanimous. (Hey. Buddhist superhero: "Equani-Mouse!") And those lyrics... that's a fair-dinkum teisho, mate.

Where nothing ever really happens and probably just as well

I've seen things really happening where it's all downhill to hell...

Too right.

The rest:

NOWHERE ELSE BUT HERE

The Pigrim Brothers

Medidebating at a fireside in this beautiful land of Oz

Could heaven be a better place than home, well supposin' that it was

If heaven is in some future with a tomorrow so unclear

Then home for me I guess couldn't better be nowhere else but here

Nowhere else but here- ooh yeah, nowhere else but here-ooh no

Home for me I guess might never be nowhere else but here

If daunted by the many, many times things don't turn out as planned

Or haunted by the feeling of that unfamiliar hand

Just listen to little honeysuckle singing sweet and clear

The sweetest honey is in the tree that's nowhere else but here

Nowhere else but here she sings, nowhere else but here

Here's where my honey is, in this tree that's nowhere else but here

Is there much that might not happen right wherever I may be

If all I gotta do is soften some of my precious certainties

Was all that toil and turmoil, just to help me understand

That heaven may be just a fancy name for some never-never-ever land

Where nothing ever really happens and probably just as well

I've seen things really happening where it's all downhill to hell

Through a devil's pass on a bolting horse, with Buckley's hope to steer

Where we could regret we never ever cared to be nowhere else but here

Nowhere else but here ahhhhh nowhere else but here...

Now I'm dreaming by this campfire gleaming in this dear old land of Oz,

Flippin' idly through the pages of the tales of the never-was

Losing interest in a future what with tomorrow so unclear

I guess maybe I'll never really need to be nowhere else but here

Nowhere else but here - oh no, nowhere else but here - for sure

Guess maybe I may never ever need to be nowhere else but here

Nowhere else but here - oh no, nowhere else but here - for sure

Guess maybe I may never ever need to be nowhere else but here

If there's one place we're all free to be, it's nowhere else but here

Topics:

acceptance,

Australia,

equanimity,

music,

Pigrim Brothers

Wednesday, 18 November 2015

WW: Home

Topics:

bread,

food,

hermit practice,

rice,

tea,

Wordless Wednesday

Thursday, 12 November 2015

Conversation

"Bashō, am I you?"

"Ie," grumbles the old man.

"Tora-san desu yo."

(Photo of Tora-san statue in front of Shibamata Station courtesy of Flickr and a generous photographer.)

Wednesday, 11 November 2015

WW: FLeetwood 6-8552

(They recently pulled a false front off this old garage and found the original façade still intact underneath it. Note the phone number, which still bears the old alphabetic exchange. And that, for those of you playing at home, is why the gold-record rock group -- all students at Olympia High -- was called that.)

Thursday, 5 November 2015

Good Podcast: Audio Dharma

This is the mouthpiece of the Insight Meditation lineage maintained by Gil Fronsdal. (I have no idea what titles are in play or how the hierarchy over there works, but Gil delivers most of the teishos, so I'm assigning him authority.)

Insight in general, and Gil in particular, offer a refreshing perspective on Buddhist practice. Gil's gentle, self-effacing delivery inspire trust, and his perspective that existence is more or less an elaborate practical joke suggests to me that he's as near enlightened as anyone in this life. (Also, as a Zenner who jumped ship for Theravada, he's an invaluable resource for Zenners; his subtle criticisms of our approach to the Great Matter are both respectful and incisive.)

About half of the teishos here are his; the other half are delivered by a host of other teachers speaking on a range of mostly life and practice topics. (You can always count on Insight to get to the point.) Treatises on sutric or koanic literature are occasionally uploaded as well.

Individual podcasts can be downloaded from the Audio Dharma website, or listeners can subscribe via iTunes or XML. Like the SFZC podcast it's an exhaustive library of teachers and topics, offered entirely free of charge, that could serve as your sole source of spoken-word teaching if you were so inclined.

Insight in general, and Gil in particular, offer a refreshing perspective on Buddhist practice. Gil's gentle, self-effacing delivery inspire trust, and his perspective that existence is more or less an elaborate practical joke suggests to me that he's as near enlightened as anyone in this life. (Also, as a Zenner who jumped ship for Theravada, he's an invaluable resource for Zenners; his subtle criticisms of our approach to the Great Matter are both respectful and incisive.)

About half of the teishos here are his; the other half are delivered by a host of other teachers speaking on a range of mostly life and practice topics. (You can always count on Insight to get to the point.) Treatises on sutric or koanic literature are occasionally uploaded as well.

Individual podcasts can be downloaded from the Audio Dharma website, or listeners can subscribe via iTunes or XML. Like the SFZC podcast it's an exhaustive library of teachers and topics, offered entirely free of charge, that could serve as your sole source of spoken-word teaching if you were so inclined.

Topics:

Gil Fronsdal,

hermit practice,

Insight Meditation,

podcast,

review,

Theravada,

Vipassana,

Zen

Wednesday, 4 November 2015

Thursday, 29 October 2015

Matthew 6:6

For some time now I've wanted to write The Big Book of Un-Preached Sermons, a disquisition on the Shadow Gospel: that body of Christic teaching that remains largely unknown to lay Christians, owing to surgical inaction by church leaders.

For some time now I've wanted to write The Big Book of Un-Preached Sermons, a disquisition on the Shadow Gospel: that body of Christic teaching that remains largely unknown to lay Christians, owing to surgical inaction by church leaders.It's a remarkably large canon.

My all-time favourite constituent, and one that continues to be a cornerstone of my Zen practice, is Matthew 6:6:

But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly.I've never heard any clerical commentary on this directive. Reasons aren't hard to divine; Christian militants often use public prayer as a form of demonstration, even confrontation. Some will performance-pray at the drop of a hat, and given the chance, force it into public spaces and government proceedings. These people don't even seem to own a closet, let alone know how to use it.

Sadly, their detractors seldom include other Christians. At least not ones objecting on doctrinal grounds. Still, the Christ of Matthew is categorical: prayer is not prayer when others can see it.

It's not a minor point. What's at issue is nothing less that the total undoing – or at least the not-doing – of the central practice Jesus gave his disciples.

Speaking of central practices, you know what else is not itself in public?

Meditation.

I've held forth many times (here and here and here and here and here) on the strange fact that Buddhism – a solitary eremitical religion founded by the solitary eremitical Buddha – has become a pyramid scheme, to the point that actual Buddhic practitioners are now viewed as heretics. Strangest of all is the contention that the only "real" practice is collective. Authentic zazen, I'm assured, only happens when you sit with others – the more, the better. I've also been informed that the solitary sesshins I sit four times a year… aren't. Same rationale: it's only meditation if someone else is watching.

The greatest danger of this hokum is not that it reverses the Buddha's teaching and lifelong example. It's that it's crap.

I've meditated in public. I was a committed Zen centre member for several years, during which I sat formal zazen in the zendo with the assembled sangha at least twice a week. Even as a hermit, I sometimes sit in circumstances where passersby may, uh… pass by. And I'm here to tell you that the moment onlookers – or even the possibility of onlookers – enter the mix, meditation goes right out the window. Now you're playing "look-how-Zen-I-am": all posture and reputation and approval. That's not practicing. It's acting.

Jesus got this. The instant others see you praying, you stop talking to God and start talking to them. In fact, you start lying to them, about talking to God. You pile sin on top of apostasy on top of wasted effort.

It's true that diligent practice can overcome this: I once experienced kensho at the end of a zendo sesshin. I stopped caring about the opinions of peers and entered a state of unselfed clarity for a few hours. But it wasn't any deeper than the kensho I've experienced alone, and the presence of others was an impediment to it, not a catalyst.

I believe collective zazen, like collective prayer, can be a valid form. It rarely accomplishes the goals of Buddhic practice, but it may achieve others that, though less vital, are nonetheless worthwhile. (It can build community and shore up personal resolve.)

However, when public displays of communion are weaponised – when they're used to intimidate or indoctrinate – then the sangha must step up and restore right action.

(The Anchorite, by Franciszek Ejsmond, courtesy of the Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

Buddha,

Buddhism,

Christ,

Christianity,

hermit practice,

meditation,

sangha,

The Rusty Ring Art Gallery,

Zen

Wednesday, 28 October 2015

Thursday, 22 October 2015

Stupid Wisdom

I always massage a broken heart with danger. Once in college, I memorialised a girlfriend's abrupt adieu by riding my bike a hundred miles, up the side of Mt. Rainier and back, in a single day.

I always massage a broken heart with danger. Once in college, I memorialised a girlfriend's abrupt adieu by riding my bike a hundred miles, up the side of Mt. Rainier and back, in a single day.It helped. I don't know why.

Not long after that I fell in love again, and not long after that, got bounced again. Days later found me high on a sheer rock face, alone, with little experience or equipment.

I almost didn't survive that one.

That September morning remains vivid, these many years later. A scent of sun-baked basalt and cool alpine breeze, the memory of grey stone driving into my gut like a lithic fist, and once again I'm crimped over the ledge, cheek pressed against the Olympics. Below, the toes of my hiking boots are wedged against a shallow nub on an otherwise featureless wall, while above I'm literally clinging by my fingerprint ridges to the shelf. Suspended between worlds, I am simultaneously of one piece with the mountain, and apart.

Backing down is not an option; toeholds are few, and I can't see to find them. I can't climb up for the same reason. So I cling, and ponder. Indian summer makes my palms sweat, and that makes them slip, in tiny jerks that send electric jolts through my body. Yet I'm strangely detached, as if it's happening to someone else.

I suck a lungful of air, and my expanding chest deducts another quarter-inch from my account.

The fall, fifty feet to jagged rocks, will surely kill me. I could channel my strength into a desperate upward surge, but my boots might slip and their weight drag me to my death. On the other hand, if I deliberate much longer, the problem will solve itself.

Calmly, I choose to panic.

Knotting the muscles in my legs, I shove off hard, back arched, arms thrust forward like an Olympic swimmer. My face slams into the outcrop, but my fingertips find a crevice. I jam my knuckles into it, lips numb and swelling, head throbbing, and dangle. My boots kick briefly in the void, then find a ripple of their own. Chin clenched against the ledge, I cling and gasp, and wait for the nausea to pass. A rivulet of blood trickles down the rock and into my tee shirt collar. But I'm well-belayed now, hanging by my own skeleton. A heavy heel flung over the rim, and I throw my arse into the job to flop myself onto the deck like a halibut.

For a long time I just laid in the hot grit, trembling, one arm tossed over my eyes. At length, choking on blood now flowing backward, I rose to half lotus, clamped a bandana over my nose, and panted through my mouth. Golden morning whispered the dry grass in the cracks. A Steller's jay screamed in the treetops below, neon blue amongst the needles. Far below that a forested valley stretched pristine to the edge of the world.

The bleeding stopped eventually, and some time later, the singing in my spine. I swallowed cold water and laid back again.

That day I decided I'd got what I came for. Since then, my heartache remedies trend to solitary journeys through remote places.

Still dangerous. But not stupid.

(Adapted from Rough Around the Edges: A Journey Around Washington's Borderlands, copyright RK Henderson. Photo of a guy doing it right courtesy of Jakub Botwicz and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

autumn,

bird,

book,

hermit practice,

Rough Around the Edges,

wildlife

Wednesday, 21 October 2015

WW: Rare mushroom

(To the best of my ability to determine, this is the European honey mushroom Armillaria cepistipes. In the late 90s, specimens collected by mycologist Tom Volk led to the first positive ID of this species in North America, at a site in the Olympic Mountains. That's just across the bay from the site of this photo. These two were part of an effusive inflorescence growing in the litter of a well-rotted log. [A former trunk of Acer macrophyllum, unless I miss my guess.]

I ate them.)

Topics:

autumn,

maple,

mushroom,

wild edibles,

Wordless Wednesday

Thursday, 15 October 2015

Humans

Where there are humans

you'll find flies

and Buddhas

Issa

(Photograph of Musca domestica joining the picnic courtesy of Thomas Besson and Wikimedia Commons.)

Wednesday, 14 October 2015

WW: 'Nother earthstar

Thursday, 8 October 2015

Christian Meditation

In the late 40s, a British Colonial Service officer named John Main began to frequent a Malaysian ashram. There, in meditation, the devout Catholic finally tasted his life's ambition: to sit in the presence of God. At length he approached the abbot about converting to Hinduism. The guru's reply astonished him:

"No."

Like most Westerners, Main assumed all religions were about signing people up. But Hinduism (and Zen) actually discourages conversion. One's path is an invaluable, hard-won treasure; throwing it away to start all over again is a bad strategy, if you can help it.

Instead, the guru told Main to find a Christian way of meditation. The idea intrigued the Anglo-Irishman. Was there such a thing? He returned to the UK, became a Benedictine monk, and spent the rest of his life researching and resurrecting a form that had indeed, he discovered, once been central to Christian practice.

As one might imagine, there was some blowback. Notwithstanding Main's watertight historical case – the Desert Fathers, a prominent early Christian lineage, made sitting a pillar of their monastic practice, as did such seminal Church figures as John Cassian and John of the Cross – many insisted that meditation was unChristian by definition, on the well-worn pretexts that "I've never heard of it before" and "non-Christians do it." (For the record, they/we also pray, though I've yet to hear any Christian call down the Lord on prayer.)

Then came 1962. In that year, Pope John XXIII convened his now-famous Concilium Oecumenicum Vaticanum Secundum, otherwise known as the Second Vatican Council. The goal of this historic in-house revolution was to modernise, democratise, and personalise the Church. Main's reconstituted meditation lineage, envisioned as a loose œcumenical affiliation of small, often lay-led groups, fit the bill perfectly. He was given the Pope's blessing and a building in Montréal, and told to make it happen. The result was the World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM), or Christian Meditation for short.

There being no Zen centre nearby when I began my practice, I sat with the local Franciscans, who led a WCCM group, for almost two years. (Nor was I alone; one of my brothers there was a Vajrayana lay practitioner.)

There I discovered that WCCM-model sitting is virtually identical to zazen. A typical weekly meeting starts with a few minutes of teaching from the group leader – generally a brief elaboration on some point of mindfulness, with supporting Bible references – and then a few bars of soothing music, ceding to silence. (Some groups use a Buddhist-style singing bowl instead of music.) Group members repeat the mantra "Maranatha" inwardly, by way of stilling their thoughts and letting God get a word in edgewise. Afterward the music comes back up, or the keisu rings, and meditation ends. There may be shared commentary, or the session may simply disband, amid smiles and "see ya next week"s. The entire ritual takes an hour.

Some groups sit Asian-style, on zafus and zabutons, while others sit on chairs, as mine did. Lotus-sitting groups may follow the Tibetan aesthetic, or Japanese Zen; somewhere there may be a Hindu one. How these matters are decided I don't know, but it's just cosmetic; the practice remains the same.

I remain a major fan of Christian Meditation, and recommend it to the many Christians I meet who voice interest in Zen or meditation. The teaching is indeed œcumenical; there are no specifically Catholic elements in it, and no need for anyone to feel uncomfortable, regardless of denomination. (And you got that from two Buddhists.)

So Christians who hunger for a meditation practice should check out the WCCM. Sadly, there are not as many groups as the lineage deserves, but most large cities have at least one. A good place to start is the WCCM website.

Failing that, contact your local Catholic parish. You might have to insist a little; even among Catholics, Christian Meditation has yet to become a household word. If it turns out there is in fact no group nearby, talk to the priest about starting one. (You don't have to be Catholic to talk to a priest or to ask him for help, yea though Protestant eyes sometimes grow large when I suggest this.)

Any road, if you're looking to "be still and know that I am God", this-here'll get it done.

"No."

Like most Westerners, Main assumed all religions were about signing people up. But Hinduism (and Zen) actually discourages conversion. One's path is an invaluable, hard-won treasure; throwing it away to start all over again is a bad strategy, if you can help it.

Instead, the guru told Main to find a Christian way of meditation. The idea intrigued the Anglo-Irishman. Was there such a thing? He returned to the UK, became a Benedictine monk, and spent the rest of his life researching and resurrecting a form that had indeed, he discovered, once been central to Christian practice.

As one might imagine, there was some blowback. Notwithstanding Main's watertight historical case – the Desert Fathers, a prominent early Christian lineage, made sitting a pillar of their monastic practice, as did such seminal Church figures as John Cassian and John of the Cross – many insisted that meditation was unChristian by definition, on the well-worn pretexts that "I've never heard of it before" and "non-Christians do it." (For the record, they/we also pray, though I've yet to hear any Christian call down the Lord on prayer.)

Then came 1962. In that year, Pope John XXIII convened his now-famous Concilium Oecumenicum Vaticanum Secundum, otherwise known as the Second Vatican Council. The goal of this historic in-house revolution was to modernise, democratise, and personalise the Church. Main's reconstituted meditation lineage, envisioned as a loose œcumenical affiliation of small, often lay-led groups, fit the bill perfectly. He was given the Pope's blessing and a building in Montréal, and told to make it happen. The result was the World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM), or Christian Meditation for short.

There being no Zen centre nearby when I began my practice, I sat with the local Franciscans, who led a WCCM group, for almost two years. (Nor was I alone; one of my brothers there was a Vajrayana lay practitioner.)

There I discovered that WCCM-model sitting is virtually identical to zazen. A typical weekly meeting starts with a few minutes of teaching from the group leader – generally a brief elaboration on some point of mindfulness, with supporting Bible references – and then a few bars of soothing music, ceding to silence. (Some groups use a Buddhist-style singing bowl instead of music.) Group members repeat the mantra "Maranatha" inwardly, by way of stilling their thoughts and letting God get a word in edgewise. Afterward the music comes back up, or the keisu rings, and meditation ends. There may be shared commentary, or the session may simply disband, amid smiles and "see ya next week"s. The entire ritual takes an hour.

Some groups sit Asian-style, on zafus and zabutons, while others sit on chairs, as mine did. Lotus-sitting groups may follow the Tibetan aesthetic, or Japanese Zen; somewhere there may be a Hindu one. How these matters are decided I don't know, but it's just cosmetic; the practice remains the same.

I remain a major fan of Christian Meditation, and recommend it to the many Christians I meet who voice interest in Zen or meditation. The teaching is indeed œcumenical; there are no specifically Catholic elements in it, and no need for anyone to feel uncomfortable, regardless of denomination. (And you got that from two Buddhists.)

So Christians who hunger for a meditation practice should check out the WCCM. Sadly, there are not as many groups as the lineage deserves, but most large cities have at least one. A good place to start is the WCCM website.

Failing that, contact your local Catholic parish. You might have to insist a little; even among Catholics, Christian Meditation has yet to become a household word. If it turns out there is in fact no group nearby, talk to the priest about starting one. (You don't have to be Catholic to talk to a priest or to ask him for help, yea though Protestant eyes sometimes grow large when I suggest this.)

Any road, if you're looking to "be still and know that I am God", this-here'll get it done.

Topics:

Benedictine,

Christian meditation,

Christianity,

Desert Fathers,

Franciscan,

Hinduism,

John Cassian,

John Main,

meditation,

Québec,

St. Francis of Assisi,

World Community for Christian Meditation,

Zen

Wednesday, 7 October 2015

WW: Screamin' Eagle

Thursday, 1 October 2015

Street Level Zen: Keepin' It On The Corner

Topics:

bird,

movie,

poem,

Street Level Zen,

the 70s,

Woody Allen

Wednesday, 30 September 2015

WW: Buddha's footprint

Thursday, 24 September 2015

3 Things I Need To Stop Doing

Decrying the forms of others. (Inwardly, I mean; at least I don't do that market preacher thing, where you call down others aloud, as if that's going to advance anyone's programme.) Sadly, some don't share my life experience; they cling to forms I find fatuous and unproductive. If only they were as insightful as I, they'd stand a chance of being as enlightened as… (wait; where was I going with this?)

Exactly. I hold my practice to a high standard; I crop out stuff that sets me back, and embrace stuff that works. But there's this annoying corollary: others realise similar progress doing things I've thrown off, or never fell for in the first place. The fact that these forms make no sense to me is immaterial. Zen is a results-based religion.

But critiquing others provides that power rush we monkeys crave. It's heroin we distil from the opium of ego.

Confusing form with practice. When I sit for a long time, I feel like a good monk. If the session is unsettled, or short, or I don't maintain a schedule, I begin to feel like a sham. To some extent, this is useful; it keeps me on the path. But the fact is, enlightenment is non-attachment. And playing look-how-Zen-I-am is attachment to approval, if only your own. Throw in onlookers, and you multiply the delusion exponentially.

Zen is about acceptance. Sometimes you can't sit as well, or as often, as you'd like. Others you can, but you don't. But sitting is just a form. Practice is looking deeply, understanding cause and effect, adjusting what can be adjusted, and letting the rest go.

I can only do what's humanly possible, whether that's limited by outside obstacles or my own shortcomings.

Confusing religious conviction with political or social values. Like everyone, I selected my religious path largely because it complemented my existing beliefs. Zen practice has helped me grind off some sharp corners, but my principles are essentially the same ones I was born and raised with.

Fact is, morality is human and individual; religion can influence it, but is powerless to establish it, even in the ostensibly devout. It's too easy to mine scripture for self-justification, or sign your liability away to some charismatic leader who will, you implicitly believe, take the karma hit if her teaching turns out to be unskilful. (She won't. It's like your tax return: you can't sign away liability.)

Yet I tend to view those who cause suffering while espousing some other religion or theory as benighted; if only they possessed the Awesome Buddhist Truth, like me.

So what am I to do about Asia? Buddhism's been going on there for 2500 years. In many Asian countries it is, or was historically, the dominant faith; it packs at least swing-vote sway in virtually all of them to this day. So nirvana on earth must have been established somewhere in Asia by now.

Go on, Google it. I'll wait.

Right understanding means distinguishing between virtue and religion. Zen doesn't recognise any secret Masonic handshake that gets us out of dutch at the hour of our death. You either practice, or you don't. What you choose to call yourself while doing so is immaterial.

Thus the world is full of satanic Buddhists and angelic nonbelievers. When everything goes to hell, I'd rather answer to a Dietrich Bonhoeffer than a Saw Maung.

This is the irony all seekers must meditate upon and transform into insight.

(Photo of Tibetan delusion chopper courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Walters Art Museum.)

Exactly. I hold my practice to a high standard; I crop out stuff that sets me back, and embrace stuff that works. But there's this annoying corollary: others realise similar progress doing things I've thrown off, or never fell for in the first place. The fact that these forms make no sense to me is immaterial. Zen is a results-based religion.

But critiquing others provides that power rush we monkeys crave. It's heroin we distil from the opium of ego.

Confusing form with practice. When I sit for a long time, I feel like a good monk. If the session is unsettled, or short, or I don't maintain a schedule, I begin to feel like a sham. To some extent, this is useful; it keeps me on the path. But the fact is, enlightenment is non-attachment. And playing look-how-Zen-I-am is attachment to approval, if only your own. Throw in onlookers, and you multiply the delusion exponentially.

Zen is about acceptance. Sometimes you can't sit as well, or as often, as you'd like. Others you can, but you don't. But sitting is just a form. Practice is looking deeply, understanding cause and effect, adjusting what can be adjusted, and letting the rest go.

I can only do what's humanly possible, whether that's limited by outside obstacles or my own shortcomings.

Confusing religious conviction with political or social values. Like everyone, I selected my religious path largely because it complemented my existing beliefs. Zen practice has helped me grind off some sharp corners, but my principles are essentially the same ones I was born and raised with.

Fact is, morality is human and individual; religion can influence it, but is powerless to establish it, even in the ostensibly devout. It's too easy to mine scripture for self-justification, or sign your liability away to some charismatic leader who will, you implicitly believe, take the karma hit if her teaching turns out to be unskilful. (She won't. It's like your tax return: you can't sign away liability.)

Yet I tend to view those who cause suffering while espousing some other religion or theory as benighted; if only they possessed the Awesome Buddhist Truth, like me.

So what am I to do about Asia? Buddhism's been going on there for 2500 years. In many Asian countries it is, or was historically, the dominant faith; it packs at least swing-vote sway in virtually all of them to this day. So nirvana on earth must have been established somewhere in Asia by now.

Go on, Google it. I'll wait.

Right understanding means distinguishing between virtue and religion. Zen doesn't recognise any secret Masonic handshake that gets us out of dutch at the hour of our death. You either practice, or you don't. What you choose to call yourself while doing so is immaterial.

Thus the world is full of satanic Buddhists and angelic nonbelievers. When everything goes to hell, I'd rather answer to a Dietrich Bonhoeffer than a Saw Maung.

This is the irony all seekers must meditate upon and transform into insight.

(Photo of Tibetan delusion chopper courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Walters Art Museum.)

Topics:

acceptance,

Buddhism,

Dietrich Bonhoeffer,

hermit practice,

meditation,

monk,

The Rusty Ring Art Gallery,

Tibet,

Zen

Wednesday, 23 September 2015

WW: Largest and oldest chestnut in the US

(The plaque below lays out the basics of the story. This American chestnut [Castanea dentata] is thought to be the largest, and possibly the oldest, left on the continent, after an introduced blight killed off virtually all of the once-ubiquitous trees. Because they're not native to the North Coast, this one had no peers to communicate the fungus. Today it's the centrepiece of a cemetery in Tumwater, Washington.)

Topics:

cemetery,

chestnut,

George Bush,

Olympia,

Wordless Wednesday

Thursday, 17 September 2015

The Buddha's Practice

"In the morning, I take my bowl and robe and go into the village to beg for food.The Buddha, according to the Anguttara Nikaya 3.63 (1).

"After my meal, I go into the woods, and gather some grass and leaves to sit on. I sit with legs crossed and a straight back and arouse mindfulness.

"Then, far from sense pleasures and bad states of mind, I do jhana."

Wednesday, 16 September 2015

WW: Sorb jelly

(Just the thing on bannocks, hermit bread, and scones.)

Topics:

autumn,

bread,

food,

hermit practice,

hermitcraft,

rowan,

Wordless Wednesday

Thursday, 10 September 2015

Hermitcraft: Champagne Plums

Here's a quick hint from Rob's Hermit Kitchen:

Here's a quick hint from Rob's Hermit Kitchen:The plums have ripened here in the Northern Hemisphere, and those with trees are being inundated by their annual surfeit of sweet, juicy fruit. Plums (also called prunes or damsons) are relatively labour-intensive to preserve, and other treatments are either specialty projects (wine) or not especially compelling compared to other options (jam).

But here's something you can do with them that's delicious and easy:

- Place a number of fresh, unwashed plums (any kind) in a non-reactive bowl.

- Mix up a slip of flour and water, about as thick as pancake batter, and pour it over them.

- Cover the bowl and leave it to work for a day or two.

- When the batter is bubbling merrily, remove the plums with a slotted spoon and rinse them clean.

- Eat.

Well, to begin with, the powdery white "bloom" you see on dark plums is yeast. (Yellow varieties have it too, it's just not as visible.) So when you immerse the fresh fruit in flour-based batter – a nutritional

medium – the yeast goes nuts and multiplies like crazy.

medium – the yeast goes nuts and multiplies like crazy.Meanwhile, water from the batter soaks into the plums, causing them to swell and opening tiny fissures in their skin. Dark streaks of plum juice in the cream-coloured batter attest to this process. (Some plums may actually split wide open, leaving little doubt about what's going on.)

Yeast from the working batter penetrates the broken plum skin, hits the sugary juice inside, and begins to ferment.

Then you eat it. I don't know how much alcohol this process creates, but it isn't much; I've eaten many of these in a sitting without feeling any effect at all.

When the plums are gone, you're left with a unique and tasty sourdough starter that makes great pancakes and coffee cake. In fact, with a little advanced planning you can pit the fermented plums, poach them in a light syrup, and use them as filling for some epic crêpes made from the batter they just came out of.

So have at it. Rarely do you get so much good for so little effort.

(Plum photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons users Sakurai Midori and Zebulon.)

Topics:

autumn,

food,

hermit practice,

hermitcraft,

recipe,

sourdough

Wednesday, 9 September 2015

WW: Hermit flag

Thursday, 3 September 2015

Career Opportunity

I recently speculated that hermits might be going mainstream, and now a friend apprises me that a Catalonian heritage-preservation association just posted a vacancy for a hermit at the ancient hermitage of Mare de Déu de la Roca (Our Lady of the Rock). The successful candidate stood to receive €1.000 for a year's service, described as "all the proper functions of a hermit". (According to the trust, these amount to showing visitors around, playing hôtelier, and not acting out of character; the announcement makes no mention of striving for transcendence, but to be fair, religious institutions rarely do that either when filling ordained positions.)

This sort of thing is actually not new; the same friend earlier directed me to the Wikipedia entry on Europe's one-time garden hermit market, wherein aristocrats supplied one of us (or someone pretending to be one of us) with rustic lodging in exchange for service as a living garden gnome. But few of those billets approached the cachet of the Catalonian opportunity.

Because the announcement is mute on spiritual matters, it's hard to know how they're defining "hermit", as opposed to "guy in a robe overseeing food service"; one gets the feeling they're really looking for a national park-style re-enactor, a college kid who wears a costume and does schtick for tourists. But I'm going to guess that Roman Catholic convictions are compulsory; it's hard to picture a waraji-wearing Zenner getting that handshake.

Nevertheless, this could be someone's entry to the lucrative and fast-growing field of eremitical monasticism. Too bad the deadline was Monday. But chin up: it looks like we're entering a seller's market.

Wednesday, 2 September 2015

WW: Mystery of the cranes

Thursday, 27 August 2015

Good Podcast: San Francisco Zen Centre Dharma Talks

San Francisco is the capital of Western Zen. The sangha there – the Western one; Asian residents were already practicing for over a century – is one of the oldest in the world, founded by Shunryu Suzuki in 1961. Today, most Zen teachers in this hemisphere have some connection with it, whether formal or incidental. (That's Soto teachers; Western Rinzai is less centralised, Korean Zen is bipolar – it has two power centres – and Thich Nhat Hanh's Vietnamese lineage is anchored in France.)

Today's SFZC is a freakin' 900-pound gorilla among spider monkeys, with three houses, an expansive endowment, and a giant sangha consisting largely of priests and priests-in-training. We hermits like to sneer about "enlightenment factories", but this-here really is.

On the other hand, it's nice to have a secure, established hub you know will be there tomorrow: reassuringly conservative, largely unchanging, eschewing relevance and doctrinal debate, and grinding out priests like a latter-day Ireland, who in turn produce reams of teachings for world consumption. In sum, SFZC – its history, its current role, the nature and limits of its authority – is a big topic among Zenners. Few of us exercise don't-know-mind in its regard.

But I'm not going to weigh in. Instead I'm going to direct you to their Dharma Talks podcast; for my money, one of Rome on the Bay's most valuable products. (To begin with, I don't have any money, and all of the teishos in SZFC's bottomless digital databank are free.)

The talks cover every Zen topic under the sun, in every style, as SFZC's diverse clerical corps take turns at the mic. A few of these lectures have about saved my life, when it needed saving. Others leave me more or less unchanged, but they're all useful and productive.

Anyway, dig it, brothers and sisters: there are a lot of them.

SFZC's podcast homepage includes links to such automatic delivery options as iTunes and RSS, as well an archive of the podcasts themselves – one per week right back to 2007 – for individual download.

So if you're up for 300-odd ordained-types throwing down some serious Zen, swing on by San Francisco's perpetual Teisho Slam. Whatever you need, you'll find it there.

Today's SFZC is a freakin' 900-pound gorilla among spider monkeys, with three houses, an expansive endowment, and a giant sangha consisting largely of priests and priests-in-training. We hermits like to sneer about "enlightenment factories", but this-here really is.

On the other hand, it's nice to have a secure, established hub you know will be there tomorrow: reassuringly conservative, largely unchanging, eschewing relevance and doctrinal debate, and grinding out priests like a latter-day Ireland, who in turn produce reams of teachings for world consumption. In sum, SFZC – its history, its current role, the nature and limits of its authority – is a big topic among Zenners. Few of us exercise don't-know-mind in its regard.

But I'm not going to weigh in. Instead I'm going to direct you to their Dharma Talks podcast; for my money, one of Rome on the Bay's most valuable products. (To begin with, I don't have any money, and all of the teishos in SZFC's bottomless digital databank are free.)

The talks cover every Zen topic under the sun, in every style, as SFZC's diverse clerical corps take turns at the mic. A few of these lectures have about saved my life, when it needed saving. Others leave me more or less unchanged, but they're all useful and productive.

Anyway, dig it, brothers and sisters: there are a lot of them.

SFZC's podcast homepage includes links to such automatic delivery options as iTunes and RSS, as well an archive of the podcasts themselves – one per week right back to 2007 – for individual download.

So if you're up for 300-odd ordained-types throwing down some serious Zen, swing on by San Francisco's perpetual Teisho Slam. Whatever you need, you'll find it there.

Topics:

cœnobite,

don't know mind,

France,

hermit practice,

Ireland,

Korean Zen,

monastery,

podcast,

review,

Rinzai,

San Francisco Zen Centre,

Soto,

Thich Nhat Hanh,

Zen

Wednesday, 26 August 2015

Thursday, 20 August 2015

Patience Meditation

I've been working on patience for 50 years now.

I may never get there.

(Photo of Finnish ice fisher courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user Peritrap.)

Wednesday, 19 August 2015

WW: Downtown deer

Thursday, 13 August 2015

Shipwrecked

I recently re-read a journal I kept in January 2003, during the period of my divorce. I was struck by the events and emotions it recorded, and particularly the role of meditation and Zen in helping me weather them. Although the period was one of the hardest I've traversed (and there are lots of candidates), in some ways I remember it as the best. The log, which I kept to gain insight into my mood swings (and, I confess, to have someone to talk to) ends up documenting a proven strategy for surviving adversity. So for the benefit of others in similar straits, I'd like to share a few reflections.

The first pages, written when my wife was still living with me but flaunting an affair – and getting in a lot of gratuitous cruelty on the side – are especially gruelling. I was living in the great Canadian G.A.N. ("God-Awful Nowhere"), 3000 miles from my family and friends, in a culture (Québec) that wasn't mine, with no car or income. In short, I was in an abusive relationship and there was no escape. No wonder those paragraphs are so full of angst and fear.

A litany of suffering is listed there: ghastly nightmares; medical issues; niggling terror; my wife's sneering, baiting jibes; and conversely, the odd oasis of peace and reflection. Most of the latter are associated with meditation; I had been sitting twice daily for nearly a year, and snowshoeing in the forest, during which I often meditated as well. Then, suddenly, after my wife announced the date of her departure, a marked drop in stress. Pointed insight, if only in retrospect.

The role of my growing monastic practice in enduring all of this is clear in entries such as:

I've long since forgiven, in light of what I've learned, and no longer take the abuse personally. But I vividly recall what life was like with her. So it's interesting now to read the lines of grief and despair I wrote the day she left.

Still, the bedtime entry, last one in the log, sums it all up:

In my case, the Four Noble Truths, and the practice they inspired – not just reading and reflecting, but the actual doing – were that solution. It may be for you as well. Any road, you might as well try; sitting is free.

The path is always there, regardless of trailhead. May we walk it with the Buddha's own diligence and humility.

(Detail from Winslow Homer's Gulf Stream courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906] and Wikimedia Commons.)

The first pages, written when my wife was still living with me but flaunting an affair – and getting in a lot of gratuitous cruelty on the side – are especially gruelling. I was living in the great Canadian G.A.N. ("God-Awful Nowhere"), 3000 miles from my family and friends, in a culture (Québec) that wasn't mine, with no car or income. In short, I was in an abusive relationship and there was no escape. No wonder those paragraphs are so full of angst and fear.

A litany of suffering is listed there: ghastly nightmares; medical issues; niggling terror; my wife's sneering, baiting jibes; and conversely, the odd oasis of peace and reflection. Most of the latter are associated with meditation; I had been sitting twice daily for nearly a year, and snowshoeing in the forest, during which I often meditated as well. Then, suddenly, after my wife announced the date of her departure, a marked drop in stress. Pointed insight, if only in retrospect.

The role of my growing monastic practice in enduring all of this is clear in entries such as:

Good AM meditation, followed by Zen study and tea. Sunny in my cell [a tiny room in which I barricaded myself, often for whole days]. Attitude rises. Productive day. Some sadness at night, before PM meditation. The sit was OK. Cut branches outside this afternoon. Felt very good during and after. Work helps.Yet I took her actual leaving surprisingly hard. Surprising, I say, because I'd quite had enough of her by then; I was eager to live in a whole house, in peace, without a demon from some Buddhist parable whose personality had dwindled to just two channels: cold and screaming.

I've long since forgiven, in light of what I've learned, and no longer take the abuse personally. But I vividly recall what life was like with her. So it's interesting now to read the lines of grief and despair I wrote the day she left.

Still, the bedtime entry, last one in the log, sums it all up:

Things remained sad and shaky until I meditated at 10PM, for almost 50 minutes. Now I'm still sad, but less so.Because the journal ends there, it doesn't detail the accruing strength and calm of the following months, due in part to the full-on monastic discipline I adopted. Nor does it record the inevitable relapses, when depression and desperation paralysed me for an hour, or a day – or in one instance, four straight days – before I took up the practice again and forged on to healing. But the seeds of that story germinate in the telegraphic chronicle of the last month of my marriage.

Things don't happen to me,I wrote toward the end,

they just happen.And then, in response to my wife's constant insistence that I was the source of all her unhappiness:

They don't happen to her, either.Zen saved my butt, and not for the last time. I'm a monk today for the same reason my grandfather remained an FDR man till the day he died: not for theory or pretence or cachet, but from sheer fire-hardened memory. So if you're suffering, be assured that you're not alone. Others have been there – others still are – and there's an end to it.

In my case, the Four Noble Truths, and the practice they inspired – not just reading and reflecting, but the actual doing – were that solution. It may be for you as well. Any road, you might as well try; sitting is free.

The path is always there, regardless of trailhead. May we walk it with the Buddha's own diligence and humility.

- Readers interested zazen [Zen meditation] will find good instructions here.

- Zen students suffering through depression or despair will find support and companionship here.

(Detail from Winslow Homer's Gulf Stream courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906] and Wikimedia Commons.)

Wednesday, 12 August 2015

WW: Forest fire sunset

Thursday, 6 August 2015

Enlightenment Kyôsaku

Topics:

enlightenment,

hermit practice,

kyôsaku,

night,

poem,

Ryokan,

The Rusty Ring Art Gallery

Wednesday, 5 August 2015

WW: County fair triumph

Topics:

food,

gardening,

hermit practice,

miracles,

possible,

summer,

Wordless Wednesday,

Zen

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)