Thursday, 22 October 2020

The Truth About Wolves and Dogs

"When a shepherd goes to kill a wolf, and takes his dog to see the sport, he should take care to avoid mistakes. The dog has certain relationships to the wolf the shepherd may have forgotten."

This line, written by Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, is incisive; equal to an revolutionary treatise, all by itself.

Reading it again, I'm reminded of several points of insight I've encountered in my past. For example, when I was a history undergrad, one of my professors described how America's white master class had forcibly converted captive Africans to Christianity in an attempt to render them docile and compliant. When, he said, the preacher fetched up against the many accounts of enslavement in Jewish scripture – accounts which rarely or never present it in a Godly light – he assured his enslaved congregation that those passages didn't mean what they seemed to mean; that they couldn't possibly understand such esoteric teachings.

"Of course, " said Dr. Francis, "this was complete nonsense. Those people knew full well what those Old Testament writers were talking about."

Later I encountered bitter capitalist denunciation of syndicalism. "Unions don't belong in The System!" they pouted. "They want to overthrow the free market!" Communism / socialism / atheism / totalitarianism / repression-depression-recession, fa-la-la-la-la.

But we lumpen learned unionism from capitalists. We implicitly understand such notions as monopoly, cornered markets, object value, possession, and the ethical justifications for acting in one's own interest, other considerations be damned. That the boss wants to kill this wolf is understandable. That he believes we've forgotten who the wolf is, is demeaning at best.

And then, of course, there's Bodhidharma. He said, "Just sit."

Literally.

That's his whole teaching.

All of it.

But in the fifteen-odd centuries since he said it, all manner of fa-la-la-la-la (or bup-po-so-en-jo-raku-ga-jo) has accrued on that small, inornate pedestal. Which was predictable; as I've quoted elsewhere, "Meditation is simple. That is why it so easily becomes complicated." You have to expect that, and accept it, and I do.

So now Zen has become a large corporate entity, complete with the usual demand for compliance, deference, and obedience, which has at length led to full-circle condemnation of Bodhidharma in some quarters. Or at least of others of his nation.

"You can't," we're assured, "possibly understand such complex, esoteric teachings."

And yet I meet more and more sheepdogs who smile and bow when we pass.

Brothers and sisters who know full well what the Old Man was talking about.

(Photo courtesy of Elxan Ehsan oğlu Qəniyev and Wikimedia Commons.)

Wednesday, 5 February 2020

WW: Me at the gates of Hell

(Not as bad as they all say. By the way, I'm totally not doing that Bodhidharma thing on purpose. I'm as taken aback as the rest of you by such photos. [Which are rare, because I seldom take any.])

Thursday, 3 October 2019

Military Meditation

Some time ago I surfed into What You Need to Know about Mindfulness Meditation, an article made available to military personnel (and everybody else) by the US Department of Defense. It leaves me a little conflicted.

As far as the information it contains is concerned, there's little enough to carp about. Yeah, dhyana probably didn't start with the Buddha, but that's minor and arguable. And the whole thing has a pronounced "meditate to get stuff" bias, but let's be honest: much in the Buddhist press does as well. And we all first come to Zen to get stuff, though the delusion softens if we practice properly.

And that's what disturbs me about this piece. Because the fact is, if you're truly practicing Zen, it's going to get progressively harder to be a soldier. Right wing politics, nationalism, certainty, fear of authority – to say nothing of killing strangers in their own homes – are things it's difficult to convince Zenners to embrace.

Which leads me to wonder what exactly the DoD is selling.

The argument cœnobites perennially throw at eremitics such as myself is that Zen needs patrolling – that without ordained, presumably accountable leadership, anybody can sell anything as Zen. And that, we're told, leads to charlatans who mislead others, individuals who mislead themselves, and the general obfuscation of the Zen path through the Red Dust World.

None of which I dispute. Rather, I question the contention that ordination eliminates these pitfalls, that the Buddha ordained any authority but his own, or that anyone has a patent on enlightenment practice. (A conviction well-buttressed by my experience of those who claim one.)

But I gotta say it, this DoD article gives off a definite whiff of caveat emptor.

It's not that anything it says is wrong. It's just that I misdoubt its motives.

Which is also how I feel about Zen teachers.

I'm certainly not opposed to Zen practice in the military. To begin with, that profession destroys just about everyone it touches – at least when fully exercised – and that creates a howling need for clear-seeing and moral autonomy. And carried forward, a Zen-practicing army would soon cease to be one, which is the next step in our evolution.

But that's what bothers me. Because this writer never openly suggests just what the war industry's aims might be in promoting mindfulness. Probably not reasoned insubordination, I'll wager. Where secular authorities advocate meditation, it's virtually always about making individuals docile, so they'll continue to commit or tolerate acts Bodhidharma (a war veteran) would condemn.

One would like to believe that any attempt to harness Zen to such ends would backfire – that the practice itself would free practitioners from quack intent. Sadly, religion has never worked that way. Zen has been weaponised before, with karmic results that outstripped its epically-appalling historical ones, and it's currently being turned to similar ends in business, education, and corrections as well.

As a one-time convicted Christian, the fear that my current path will become as debased as the former is very real. This practice is vital; too vital to allow careerists to usurp its brand. That road leads to the utter annihilation of Zen, as it has other religions.

And the last thing we need around here is yet another cargo cult.

I hope military personnel, active and discharged, around the world learn about Zen; that those who are suffering know that it might keep them breathing; and that those who are in pain will give it an honest shot and see if it helps. Some of our best teachers came from that world, channelling the laser insight they scored waging war – and the iron discipline their instructors gave them – into kick-ass monasticism. (The two callings are remarkably similar.)

Because it's not that there's nothing soldierly about the mindfulness path. It's just that it leads to a diametrically opposite destination.

(Photo of the Ryozen Kannon, Japan's WWII memorial, courtesy of Bryan Ledgard and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thursday, 25 May 2017

Facing the Wall

My brother Fletcher – formerly an ordained Zen monk, now an ongoing seeker after insight on another path – recently described to me his initiation as a novice at Tassajara. (That would be the largest Soto monastery in the States – possibly largest in the whole West – and a dependent house of San Francisco Zen Center.)

My brother Fletcher – formerly an ordained Zen monk, now an ongoing seeker after insight on another path – recently described to me his initiation as a novice at Tassajara. (That would be the largest Soto monastery in the States – possibly largest in the whole West – and a dependent house of San Francisco Zen Center.)His story was typical: the ranking monks shut him in a room with other boots and made them meditate for five days straight. Is that OK? Maybe. Maybe not. Feel free to undertake the koan.

But the part of Fletcher's tale that most seized me was his coping strategy: he began chanting "100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall" in his head, and continued doing so throughout the ordeal. In fact, he says, "100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall" remained a go-to mantra through the course of his considerable monastic career.

I like this on several levels. First, as juvenile as its lyrics may sound, "100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall" is basically what the Ancestors instructed us to do when we sit. My technique is theirs: I count my breaths from 1 to 10, then start again, until I'm done. All Fletcher changed was the number of reps.

His approach is also refreshingly free of twee chinoiserie. You know what else is free of twee chinoiserie? Zen. Or it was, until it acquired "Ancestors". Once upon a time we were famous – scorned, actually – for our coarse working-class pragmatism, and also our impatience with Confucian obsequium. "Get it done," Bodhidharma said (more or less).

And Fletcher did. By his account, the old summer camp ditty (was this ever a real drinking song – don't drinking songs end every so often so the singers can drink?) got the job done: it kept his discursive mind occupied so it couldn't stuff every silence with worry, regret, and drama, and it afforded the rest of his consciousness an opening to engage the Great Matter.

Sounds like enlightenment practice to me.

(Photograph of Tassajara Zen Mountain Center courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Thursday, 5 January 2017

Hard-Condition Meditation

(Readers who are new to meditation might find How to Meditate useful. More experienced meditators might also appreciate Meditation Tips.)

Our Ancestors, from the Buddha forward, gave specific instructions for setting up a meditative environment. The particulars are as universal as they are basic:

Sit lotus or facsimile on a cushion in a darkened, but not dark, room.* Maintain temperatures on the cool but not cold side. Exclude distracting sights, sounds, and smells. And (in some versions) close all doors and windows to prevent stray breezes from breaking your concentration.

(*Cœnobites generally insist on sitting indoors. Since they also do most of the teaching, the "conventional" instructions reflect their values. Hermits, for our part, typically accept, and may even prefer, sitting outdoors. For a brief discussion of this difference, see the end of this post.)

I can testify that these instructions work. In fact they're thunderously effective, and once you've created such a setting and positioned yourself in the midst of it, it's harder to avoid zazen than to embrace it.

'Course if I had ready access to such an environment, I wouldn't need enlightenment. I'd just move in and call it a life.

So for my neighbours here south of the long-lived god realm, I'd like to kick off this new year of practice by sharing some hard-earned pointers for hacking meditative space out of an unmeditative existence.

Unhelpful sounds are one of the most common and troublesome challenges. If you can't get away from them or wall them out, you'll find modern headphone technology a godsend. Queue up something contemplative on your iPod, computer, or other device and turn it up just far enough to allow you to meditate. Ideally the masking material will not include human voices (though unintelligible chanting may work for some) and will not otherwise draw your attention in any persistent way.

The result isn't pure zazen, but it beats no sitting at all.

Nature sound recordings (surf, forest, rain) work best for me. Wordless ASMR videos are good too, though they can turn into a relaxation session if you're sensitive to ASMR. This isn't the end of the world either, as long it doesn't replace zazen practice entirely.

Though New Age or religious music often markets itself as a meditation aid, I find it stimulates discursive brain function and prevents zazen.

Finally, by all means don't overlook good old earplugs. For some reason this simple, cheap solution is largely unknown to a large segment of the population, but those disposable foam plugs working people use to avoid going deaf on the job clear all kinds of sound-borne obstructions. They're most effective on low-pitched noises, such as machinery, but greatly attenuate music, television, and voices as well.

Foam earplugs can be had at any hardware store. Having a pair ready on the nightstand can mean the difference between a sleep interrupted and a sleep ruined.

Physical inconvenience is yet another pernicious trial, particularly if you're infirm, or far from your zafu. Meditating in a modern office chair can solve this. Scientifically-designed to distribute your weight as widely as possible, these ubiquitous devices are fully equivalent to a buckwheat zafu and good zabuton. They're a great fall-back for us cushion-sitters, and if you can't sit lotus at all, they flat-out give you your practice back.

Use is straightforward: lower the seat until your feet are flat on the floor. Place your hands in mudra, if comfortable; if not, rest them on your thighs. Meditate.

There may not be any statues of the Buddha sitting in a polyester swivel chair, but you're doing exactly what he did all the same, and that's all that matters.

Note: most how-to-meditate guides say that if you sit in a chair, you must not touch the back. I've sat both ways in an office chair and enjoyed equal success. I still usually sit bolt-upright, because I'm a macho puritanical Japanese-trained Zen Buddhist and there's an angel in heaven who keeps track of these things and will reward me after death. But if you'd rather sit comfortably, research suggests there ain't one difference.

Bad smells are something beginners seldom anticipate, but for my money they're the hardest thing to sit with; all the more since zazen strops your sense of smell to a razor's edge. Trouble is, barring hard-helmet diving gear, you can't insulate yourself from the atmosphere and live.

I've already covered the value of incense for mitigating stench, even deeply nauseating ones like sewage and cigarettes. The trick is to pony up for the good stuff; cheap incense is one of the stinks we're trying to escape.

Different religions (Christian, Buddhist) and traditions (Tibetan, Japanese) cultivate different vibes, so you might have to shop around to find an incense that works for you. But high-grade Vajrayana, Zen, and Roman Catholic incense have all worked for me. Hippy Crap®, on the other hand, makes me gag.

Sometimes you can't sit. (Like, at all.) Maybe your rooming situation won't permit it. Maybe your schedule makes seated zazen impossible. In such situations it's legal to meditate in other positions and places. My two favourites are in the bath and in bed.

For the bath, fill the tub with hot water, sit down in it, fold your legs lotus-style, and lie down on your back. This has the further benefit of enveloping you in a warm, soundproof, weightless cocoon. I've had some fabulous "sits" like this.

For the bed, same drill: tuck self in comfortably, assume position, and meditate.

You're likely to fall asleep in both cases – I actually do it on purpose at night – but you'll get in some good meditation in the meantime. (You might also drown, in the bath tub. So far I've always woken up, coughing and spitting, before that happened, but if you have some kind of condition that might preclude this, you should probably avoid bath-sitting.)

And of course there's always real meditation. Instructions be damned, the Ancestors advised us to meditate with our surroundings, not apart from them. Try befriending your irritations, looking deeply, understanding your annoyance, and accepting them and it. Doesn't always grow corn, but I've had some ringing successes. At any rate, sitting with my own frustration is one of the most useful practices I do.

Which brings me at last to the indoor-outdoor question. The Buddha sat outdoors. Bodhidharma sat half outdoors: facing the wall beneath a tree in an enclosed courtyard.

Yeah, there are more distractions outside. Stuff falls on your head. Wildlife walks by. It gets hotter and colder. Bugs, uh… bug you.

But I like it. These reminders that "the world" isn't a synonym for humanity powerfully support my practice. Also, sitting lotus in a stifling meditation hall, as I've been constrained to do at the zendo, with sweat soaking my clothes and heart-rate turned up to 11 by the sauna-like air, because going outside would "distract" me, is dumb.

And nothing that's dumb is Buddhist.

But whatever your perspective, do what works, without fail. If you find manufactured discomfort spiritually useful, have at it. And if Norwegian death metal creates mindful space for you, then by all means, with my delighted brotherly blessing, bang your head in good health.

(Photograph courtesy of Stuart Heath and Flickr.)

Thursday, 22 December 2016

Christmas Koan

| Pictured: not the Buddha. |

(By the way, if he happens to read this, may I suggest you refrain from commenting on others' beliefs until you know, at minimum, whether they pray, and if so, to whom.)

We Zenners find this nonsense especially grating since we barely even acknowledge the figure they're referring to.

For the record, the dude in the above photo is Hotei (Budai, Pu-Tai, 布袋, Bố Đại...). Not the Buddha. Not a buddha. Not even a significant legendary figure, like Fudo or Kanzeon. Just a rankless Chán monk of the Liang Dynasty.

Not that my brother Hotei didn't have his noteworthy points. First off, unlike most Buddhist monks, he was fat. (Note that the actual Buddha once starved himself nearly to death, and then adjusted his practice to embrace, shall we say, non-stupid asceticism. That's why he's usually depicted as sensibly slim, and occasionally as terrifyingly emaciated, in admiration of his earlier, if misguided, conviction.)

Hotei's girth was all the more miraculous because he was a begging hermit. (High five to the Homeless Brothers!) How you maintain such a waistline on handouts is one of the mysteries of his practice.

Especially since he gave away everything he got. Hotei carried this dimly-sourced loot in a bag over his shoulder, which, upon deposition, turned out to be mostly filled with sugary treats that he handed out to children like… (Sorry. Even I can't go there.)

You see this coming, right?

Not yet?

OK, dig this: the central practice of Hotei's monastic rule was laughter. He was always cutting loose with a big, jolly laugh that announced joy and peace to the world, as he humped a bottomless bag through town on his fat back, doling out presents to every child...

Anybody?

Oh, come on! Now you're just trying to piss me off.

The reason you see more statues of Hotei than Gautama in Asia is the same reason you see more Santas than Jesuses at Christmastime: he's more fun, less threatening, and doesn't remind people of suffering.

And it's that last bit I like to meditate on.

Hotei is unpopular among modern Zenners because he's embarrassingly emotional, dangerously untamed – wandering around teacherless, eschewing all acts of devotion save his self-authored laughter practice – and worst of all, he does that annoying Bodhidharma thing of preaching no-key enlightenment.

Don't waste time bowing and chanting and folding things just so and being obedient to this and that, says Hotei. Especially, don't confuse misery with discipline.

Bodhidharma said "just sit." Hotei says "just laugh."

And that's what offends us. Because if Bodhidharma crapped on social ambition and Confucianism and gracious deference to hierarchies, at least he wasn't ho-ho-ho-ing it up in the town square, rubbing our pious faces in it.

"You're in pain?" says the fat old hobo. "I hate it when that happens. But don't sweat it, because sooner or later, one way or another, your problems are doomed. Hey, they can't survive without you, can they?"

And then he laughs. Because that's freakin' hysterical.

Therefore, in honour of Christmas, and to bow in ironic deference to my unpretentious brother, I offer fellow seekers the Koan of Hotei. To my certain knowledge, it's the only nod to the Buddhist Santa Claus in our entire canon. It's also my favourite koan. (A distinction it shares with all of them.)

So:

A monk asked Hotei, "What is the meaning of Chán?"

Hotei put down his bag.

"How does one realise Chán?" the monk asked.

Hotei threw his bag on his back and walked on.

Happy holidays, brothers and sisters. See you on the road.

|

| Jolly old Gautama. |

(Photos courtesy of Helanhuaren [Hotei figurine], Akuppa John Wigham [emaciated Siddhartha statue], and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thursday, 10 November 2016

Courage Kyôsaku

"To dwell in the three realms is to dwell in a burning house."

Bodhidharma

(Photo of The Blue Fudo – National Treasure of Japan, Heian period [794-1185 CE] – holding his ground in the fires of Hell, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Thursday, 26 November 2015

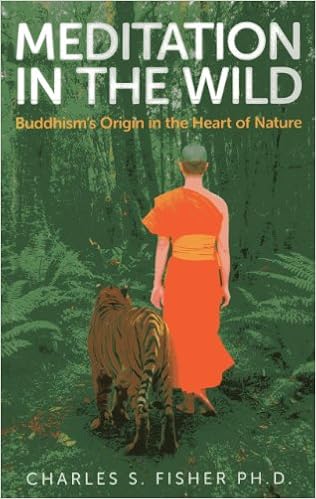

Good Book: Meditation in the Wild

In Meditation in the Wild: Buddhism's Origin in the Heart of Nature, Charles S. Fisher writes:

Not that it's easy; as a quotation from Theravada scholar Richard Gombrich points out:

But outdoor practice was hard – even harder than it is now – with dangerous wildlife and tribal warriors still ruling the outback, and the impulse to organise was strong. Yet The Kindred Sayings of Kassapa show the Buddha "bemoan[ing] the passing of the forest way of life and criticis[ing] those who depart from it"; he may have gone so far as to advocate a straight-up return to hunter-gathering, according to texts that describe his sangha living off the land, hunting game, and never returning to the Red Dust World. The fact that Buddhism spread to new lands precisely as Indian forests were clearcut leads one to wonder what exactly the motivations of those first "missionaries" were. (It also throws intriguing light on the Bodhidharma story. Canon holds that when asked why he came all the way to China to sit under a tree, he replied: "Because this is the best tree in the world." Perhaps his actual words were something like, "Because you still have trees.")

Conjecture aside, the founding generation of Buddhists exhorted aspirants to imitate Gautama literally. Mahakasyapa, a member of the Buddha's inner circle, died a loud and proud hermit, as did no less than Sariputra, of Heart Sutra fame. Finally, reports of early Western observers – Greek travellers – confirm that the first Buddhists were itinerants, without clergy or temples.

But as the movement grew respectable and sedentary, hermits were increasingly viewed as "unsocial, possibly antisocial, and potentially dangerous to established Buddhism." This last repeated pious tales of the Buddha's forest practice, but openly discouraged others from emulating it. Old-school monks, known as "mahallas", were accused of backsliding and dissolution and reviled by the ordained. (Some verses quoted in Wild are stunningly similar to the rant St. Benedict unleashed on Sarabaites and Gyrovagues at an identical stage in Christian history.)

To be sure, over the past 2500 years Buddhist back-to-the-landers have continued to crop up; modern Zen and Theravada are remnants of two such rebellions. Possibly Wild's greatest gift is the two and half millennia of these forgotten reformers it lifts from obscurity. Along the way its author weighs the relative merit of individual cases. He reviews Issa's suburban eremiticism, which echoes most current hermit practices, with guarded approval, but – interestingly – takes Bashō, Ryokan, and Kamo No Chomei firmly to the woodshed.

And that's where I get off the train. In these passages, Fisher reminds me of Thoreau's critics, calling down suspects for claims they never made. His indictment of Bashō does ring, but he repeatedly spins individual innovation in self-directed practices as weak or duplicitous; in the case of Ikkyu, he indulges in crass bourgeois morality. Somehow, in all of his research on us, he missed our core vow: "I will neither take nor give orders." I may raise an eyebrow at others (OK: I do raise an eyebrow at others) but ultimately I have no right to deplore them. Licence to judge is a delusion of the ordained.

But this mild annoyance in no way diminishes the significance of Fisher's work. His journalism is both intrepid and thorough, penetrating the Thai forest lineage – a modern restoration movement – at length and documenting the gradual deterioration of Zen, from Bodhidharma's boldly-planted hermit flag, to the dismissal of 19th century hermit Ryokan (his own beefs with him aside) as a "lunatic". He finishes with an account of his own brushes with eremitical practice (Fisher is not a practising hermit per se, but is attracted to our forms) and a light survey of four contemporary American hermits. All in all, it's the most comprehensive treatment of the subject I've found anywhere.

And I found it impossible to put down. With any luck, Meditation in the Wild will stand for many years as Eremitical Buddhism 101 for sincere students of the Buddha's way.

"Buddhism was born in the forests of India. [...] The Buddha found his original revelation while practicing as a forest monk. [...] He developed an understanding of nature which would become part of the remedy he proposed for the problem of human discontent. [...] He chose wild nature - the evolutionary context in which humans arose - as the place to do this. [...] He went to the place in the human mind where there is understanding without words."The next 315 pages go on to prove his thesis.

Not that it's easy; as a quotation from Theravada scholar Richard Gombrich points out:

"So much of the material attributed to [the Buddha]… is so obviously inauthentic that we can suspect almost everything. In fact, it seems impossible to establish what the Buddha really taught. We can only know what early Buddhists believed he taught."And this, as it happens, is very different from what we've been told. For example, some of their records maintain that Gautama encountered his famous Four Sights on the way to the forest, where he sat and pondered what he saw. Others suggest that the pivotal debate between Mara and Gautama on the eve of his Enlightenment was actually about the Devil's contention that the young man had no right to strive to end suffering. All those statues of him touching the earth, they contend, depict him saying, "Check it out, dipstick: I'm home. Go find someone who cares."

But outdoor practice was hard – even harder than it is now – with dangerous wildlife and tribal warriors still ruling the outback, and the impulse to organise was strong. Yet The Kindred Sayings of Kassapa show the Buddha "bemoan[ing] the passing of the forest way of life and criticis[ing] those who depart from it"; he may have gone so far as to advocate a straight-up return to hunter-gathering, according to texts that describe his sangha living off the land, hunting game, and never returning to the Red Dust World. The fact that Buddhism spread to new lands precisely as Indian forests were clearcut leads one to wonder what exactly the motivations of those first "missionaries" were. (It also throws intriguing light on the Bodhidharma story. Canon holds that when asked why he came all the way to China to sit under a tree, he replied: "Because this is the best tree in the world." Perhaps his actual words were something like, "Because you still have trees.")

Conjecture aside, the founding generation of Buddhists exhorted aspirants to imitate Gautama literally. Mahakasyapa, a member of the Buddha's inner circle, died a loud and proud hermit, as did no less than Sariputra, of Heart Sutra fame. Finally, reports of early Western observers – Greek travellers – confirm that the first Buddhists were itinerants, without clergy or temples.

But as the movement grew respectable and sedentary, hermits were increasingly viewed as "unsocial, possibly antisocial, and potentially dangerous to established Buddhism." This last repeated pious tales of the Buddha's forest practice, but openly discouraged others from emulating it. Old-school monks, known as "mahallas", were accused of backsliding and dissolution and reviled by the ordained. (Some verses quoted in Wild are stunningly similar to the rant St. Benedict unleashed on Sarabaites and Gyrovagues at an identical stage in Christian history.)

To be sure, over the past 2500 years Buddhist back-to-the-landers have continued to crop up; modern Zen and Theravada are remnants of two such rebellions. Possibly Wild's greatest gift is the two and half millennia of these forgotten reformers it lifts from obscurity. Along the way its author weighs the relative merit of individual cases. He reviews Issa's suburban eremiticism, which echoes most current hermit practices, with guarded approval, but – interestingly – takes Bashō, Ryokan, and Kamo No Chomei firmly to the woodshed.

And that's where I get off the train. In these passages, Fisher reminds me of Thoreau's critics, calling down suspects for claims they never made. His indictment of Bashō does ring, but he repeatedly spins individual innovation in self-directed practices as weak or duplicitous; in the case of Ikkyu, he indulges in crass bourgeois morality. Somehow, in all of his research on us, he missed our core vow: "I will neither take nor give orders." I may raise an eyebrow at others (OK: I do raise an eyebrow at others) but ultimately I have no right to deplore them. Licence to judge is a delusion of the ordained.

But this mild annoyance in no way diminishes the significance of Fisher's work. His journalism is both intrepid and thorough, penetrating the Thai forest lineage – a modern restoration movement – at length and documenting the gradual deterioration of Zen, from Bodhidharma's boldly-planted hermit flag, to the dismissal of 19th century hermit Ryokan (his own beefs with him aside) as a "lunatic". He finishes with an account of his own brushes with eremitical practice (Fisher is not a practising hermit per se, but is attracted to our forms) and a light survey of four contemporary American hermits. All in all, it's the most comprehensive treatment of the subject I've found anywhere.

And I found it impossible to put down. With any luck, Meditation in the Wild will stand for many years as Eremitical Buddhism 101 for sincere students of the Buddha's way.

Thursday, 30 January 2014

Kyôsaku Kyôsaku

Two days ago I found this teaching in my Twitter feed:

"Treat non-useful thoughts like undesirable smells: don't dwell on them, don't identify with them, don't get attached to them, don't get lost in them - simply let them float away."

It's Zen at its trenchant best: laconic, practical, self-evident. A classic and useful taste of humanity's most down-to-earth religion. I immediately stored the passage for a later Kyôsaku and went about determining credit. (It was attributed only to "tad".)

After some digging, I discovered that "tad" is not a guy, it's a business. Specifically, it's something called The T.A.D. Principle, which is apparently a book, though the advert is coy on this point. It's even coyer about a later product, the 21-day meditationSHIFT Programme, which costs $29 and promises to revolutionise your life, though it too is evidently 15th century technology. (I could be wrong; neither of these "works" is described as a book. They aren't described as anything.)

About here you'd expect me to go off on a rant about New Age self-help hucksters. And I'd like to. But the thing is, I've spent some time perusing T.A.D.'s promotional copy, and found not a word I could dispute. It's all straight-up conventional Zen. Great stuff, in fact. No doubt the testimonials ("Thank you for teaching me how to meditate, and how to get control of my runaway mind! [emphasis original]") are sincere and authentic.

And while that $29 price tag (fair price for a book of this kind, if it is a book) is technically selling Zen – and that's immoral – your local Zen master might put the bite on you for much more. Folks have paid thousands; even tens of thousands. And frankly, if you've reached the place where you can't breathe – from grief, depression, or other forms of world-weariness – a handful of coppers spent on the right book could save your life.

So I guess my only serious objection is the implied claim that the unnamed author or authors invented this stuff. Which he, she, or they did not. If the marketing snippets are representative, this is plain old brilliantly effective Zen. To be sure, the word "Zen" appears nowhere on the site, but so long as the author or authors don't assert some bogus patent, the karmic implications seem moderate.

On the other hand, my patented Crusty Old Hermit Programme is cheaper and quicker than other leading brands. If you click before midnight tonight, you can take advantage of our Special Introductory Offer: to wit, nothing less than the FULL TEXT of our Dynamic Life-Coachment S.E.L.F.-Training Modality:

"Get over yourself."

Free to you, because you look like a nice person. But I wouldn't say no to a cup of tea.

(Portrait of original crusty old hermit Bodhidharma courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

"Treat non-useful thoughts like undesirable smells: don't dwell on them, don't identify with them, don't get attached to them, don't get lost in them - simply let them float away."

It's Zen at its trenchant best: laconic, practical, self-evident. A classic and useful taste of humanity's most down-to-earth religion. I immediately stored the passage for a later Kyôsaku and went about determining credit. (It was attributed only to "tad".)

After some digging, I discovered that "tad" is not a guy, it's a business. Specifically, it's something called The T.A.D. Principle, which is apparently a book, though the advert is coy on this point. It's even coyer about a later product, the 21-day meditationSHIFT Programme, which costs $29 and promises to revolutionise your life, though it too is evidently 15th century technology. (I could be wrong; neither of these "works" is described as a book. They aren't described as anything.)

About here you'd expect me to go off on a rant about New Age self-help hucksters. And I'd like to. But the thing is, I've spent some time perusing T.A.D.'s promotional copy, and found not a word I could dispute. It's all straight-up conventional Zen. Great stuff, in fact. No doubt the testimonials ("Thank you for teaching me how to meditate, and how to get control of my runaway mind! [emphasis original]") are sincere and authentic.

And while that $29 price tag (fair price for a book of this kind, if it is a book) is technically selling Zen – and that's immoral – your local Zen master might put the bite on you for much more. Folks have paid thousands; even tens of thousands. And frankly, if you've reached the place where you can't breathe – from grief, depression, or other forms of world-weariness – a handful of coppers spent on the right book could save your life.

So I guess my only serious objection is the implied claim that the unnamed author or authors invented this stuff. Which he, she, or they did not. If the marketing snippets are representative, this is plain old brilliantly effective Zen. To be sure, the word "Zen" appears nowhere on the site, but so long as the author or authors don't assert some bogus patent, the karmic implications seem moderate.

On the other hand, my patented Crusty Old Hermit Programme is cheaper and quicker than other leading brands. If you click before midnight tonight, you can take advantage of our Special Introductory Offer: to wit, nothing less than the FULL TEXT of our Dynamic Life-Coachment S.E.L.F.-Training Modality:

"Get over yourself."

Free to you, because you look like a nice person. But I wouldn't say no to a cup of tea.

(Portrait of original crusty old hermit Bodhidharma courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Friday, 11 February 2011

Bite Me, Batman!

|

Candid portrait of my practice: written and recorded teachings; twine and rings for making fudos; mat where my bowl rests; laptop, sole link with the outside. |

Christ and the Buddha defined monastics in astoundingly similar terms: They answer a unique call and walk a personal path. They reject personal ambition, and family and social obligation. Though encouraged to seek each other out for wisdom and solace, they are self-ordained. Neither Jesus nor Gautama recognised any other clerical model.

Such renunciates are called monks, from the morpheme mono-, meaning "single."

Unfortunately, as individuals who follow a personal call and have no use for human authority or the credentials it sells, we quickly fell afoul of power. As a result, The Man redefined the word as "one who lives in a monastery," that is, a "place where people are alone together." (Hey, don't look at me.) Monasteries are owned and operated by The Establishment, which claims sole right to train and ordain residents. Let's be clear: there is no scriptural basis for this presumption, or this practice.

Today, ordained monastics have all but wiped alternatives from memory, so that an old-school monk like me risks being labelled a fraud for claiming the title. But I do anyway.

Later we stick-and-sandal types took the term hermit, by way of clearing up the confusion, but this too has become problematic. For starters, it calls up images of a crotchety old man who hates people and lives in the woods and never bathes. And I'm not that crotchety.

By whatever name, monastics who live by a rule of their own authorship have been around since the first human suspected there was more to life than the opposable thumb. To my certain knowledge, only the Roman Catholic church recognises us officially today. And the Vatican has been under pressure to ordain us ever since, but so far, successive popes have defended the eremitic vocation.

I confess I'm a bit envious of my Catholic brothers and sisters. Thanks to papal protection, there is now a sanctioned hermit movement within the Church that helps to dampen, if not eradicate, the sniping. Most Catholics I meet have still never heard of us, but the ordained monastics have, and that's huge.

Zen, sadly, is another matter. Although one of the most hermit-bound traditions on earth, the current Zen establishment is largely hostile to free-range monks. It's koanic, really: the Buddha was a hermit; Bodhidharma was a hermit; Huineng, father of all extant Zen lineages, was arguably a hermit; Ryōkan, one of our most beloved ancestors, was a hermit; Ikkyū, whose teachings are an essential antidote to Buddhist hypocrisy, was a hermit. But the Asian cultures in which Zen is rooted have a demonstrable contempt for individual initiative, and that has led us into a cul-de-sac of guru-worship. Today, Zen hermits are often accused of imposture and egotism for living the Buddha's own given precepts. The resentment is mutual and conspicuous, particularly in the West, where autocracy is dimly viewed and self-sufficiency a virtue.

For the record, I consider ordained monasticism legitimate, and even necessary. Alright, it's not scriptural. So what? Stuff doesn't have to come from the sutras to be valid. If it weren't for monasteries, what would I study? Most Zen teachings are generated, and all are curated, by ordained monks. The typical hermit has been inside before. I have done, and am likely to do again. The monastery is an important touchstone, and a weighty counterbalance to the hippy-dippy narcissism of hermitry. I shudder to think what we would become without it. Finally, it's an effective, irreplaceable practice for many who are drawn to that path, as synonymous to their lives as mine is to mine.

In sum, if I had a million dollars, I'd give it to a monastery. What the hell is a hermit gonna do with money, anyway?

But when the ordained sangha dismiss us homeless brothers as heretics or wannabes, or insist that our sacred birthright path leads nowhere but astray, then I just have to say it, loud and clear:

"Yo, Batman! You got a problem, you talk it over with the Buddha. I got more important lives to live."

Thursday, 20 January 2011

Why Doesn't This Barbarian Have a Beard?

|

| This blog brought to you by the Loyal Order of Crazy White Boys. |

Recently a sangha sister said one of the nicest things I've heard in a long time. She compared me to Bodhidharma. Like the best of kind words, it was "soit dit en passant," an aside dropped on the way to another point. But for a modern hermit, it was sustenance.

Bodhidharma was the founder of Zen. A war veteran from India, or possibly Persia, he left for darkest China in the early 5th century, having grown disgusted with the violence of the "civilised" world and the self-satisfied nature of established Buddhism. Determined to practice exactly as the Buddha instructed, he sat zazen for nine years, eschewing all outward forms of practice. In the end he was enlightened, and his "just sit" teaching opened the path of Chàn (Zen).

As you can see, my man Bodhidharma was a white guy, with the big nose, spidery hands, and full beard typical of his race. This fact remains central to his historical identity,

|

| Photo taken months ago in front of my meditation hut. I swear I had no idea. |

Apparently, other unruly Caucasian monks may also raise his iconic image in some minds. Of course, I got a long way to go before I'm Bodhidharma. Any round-eyed rebel can go around in a robe and beard and sneer a lot; it's the sitting that makes the saint. But in a world and tradition where hermits are often suspected and rejected, it's nice that someone noticed the family resemblance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)