Liberate yourself from everything that doesn't concern you.

Liberate yourself from everything that doesn't concern you.

Don't depend on people or on situations.

Look for your refuge and your help only in God.

– A Franciscan hermit in my Bluesky sangha.

(Photo of a lotus on the grounds of the Franciscan Monastery (sic) of the Holy Land in America courtesy of Clare Tallamy and Unsplash.com)

"You should only ever take a vow if you're already doing that anyway."

Sounded a bit paradoxical at the time, but as I've since learned it's exact.

People tend to take vows (or precepts, as we call them in Zen) as a declaration of intent – generally, to abstain from some urge they would otherwise indulge. And this negative emphasis – "I will forgo", rather than "I will accept" – won't convince your impulses to stand down.

"All you're doing is setting yourself up for failure," according to the friar. "And a vow you don't keep just creates greater discontent, more suffering, and more doubt that you'll have to overcome."

Instead, he suggested, you should vow to do something you've already come to do naturally; a principle you've resolved, if unconsciously, to refer to in future decisions. Then the vow is conscious confirmation of insight, instead of a promise to behave as if you already have insight you don't in fact have.

It took me years to grasp fully the truth of this teaching, but like all good resolutions, it came when needed.

In my case, the precept in question was the one governing my sexual life. I should state up front that I have serious problems with the role sex plays in my culture, the importance it's conceded in our ethical and spiritual domains, and the superstitions we weaponise to enforce them.

Thus I was reluctant to address the issue at all, as a red herring, when I was working to found an authentic Zen practice to free myself from such delusions.

There's also the fact that for me, conduct toward members of the opposite sex has always been governed by my desire for companionship, with the sexual component solidly subservient to that; since puberty I've had zero interest in sex before or in absence of a relationship.

So the very nature of a sexual conduct vow struck me as beside the point – something that doesn't address my problem, and therefore a waste of time.

Finally, the second dependent vow of my Rule clearly states,

I will honour my karma.

And contrary to common Western misconception, karma isn't just the bad stuff that happens to you. So at that time I reckoned that to deny true love, if fell from the sky, would have, to quote the catechism of my youth, "almost the nature of sin".

Therefore, the precept I took was, "I will not initiate courtship." And I gave myself leave to lay even that aside if a solid case for it could be made.

I believe that was wise on my part, especially since adapting that precept to circumstances proved extremely instructive. And particularly because some of those circumstances were ultimately painful and regressive.

Which led me a few years ago to the Final Precept – the big one, the one everybody thinks of when you say "monk".

And by that time, like the friar said, it was really academic.

Because by then I'd meditated for years on my lifelong search for love and belonging, and especially on the sustained train wreck that pursuit of same has been over my lifetime.

I came to the conclusion that the investment was underperforming, and speculated on what might have been gained had I directed those resources elsewhere.

Toward my karma, for example. (If women wanted me, they'd've come looking for me.)

Toward things that have in fact brought peace and purpose. (My relationship with the planet, my Zen practice, the slow but steady opening of my mind and heart to The Great Not-Me.)

And especially, toward my monastic vocation. Of every angle I've worked since birth, it's the one that has consistently performed, without making anything worse. Had I initiated this practice at 16, where might I be today?

Somewhere, that's where.

So I married my Path.

And just like my Christian comrade told me, when at last I took the Final Precept, it was positive – "I will cleave to the path that works" – and not simply "I will refrain from sex", which vow, taken in a vacuum and without clarity, would probably not even stick.

Most importantly, it was moot. I no longer required convincing, and no deep existential temptation threatened my acceptance of it.

Now, when the possibility of courtship flickers, I remind myself that I'm otherwise committed. And that the partner in question is unfailingly faithful.

And there is zero cause to fear either will change.

(Photo courtesy of Chris Yang and Unsplash.com.)

Some time ago I had the good fortune to spend a month in Guatemala. While in the ancient capital I visited the tomb of Hermano Pedro, a Franciscan saint who looms large in the faith and history of that country.

Some time ago I had the good fortune to spend a month in Guatemala. While in the ancient capital I visited the tomb of Hermano Pedro, a Franciscan saint who looms large in the faith and history of that country.

Preserved there is Pedro's old cell, wherein visitors can meditate on the meagre possessions of a man who gave his life to advocating for and serving the poor. It boils down to one change of clothing; a chair and a walking stick; a bed sheet and sundry devotional items; and a human skull, used by Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu monastics in times past to keep their head in the game, so to speak.

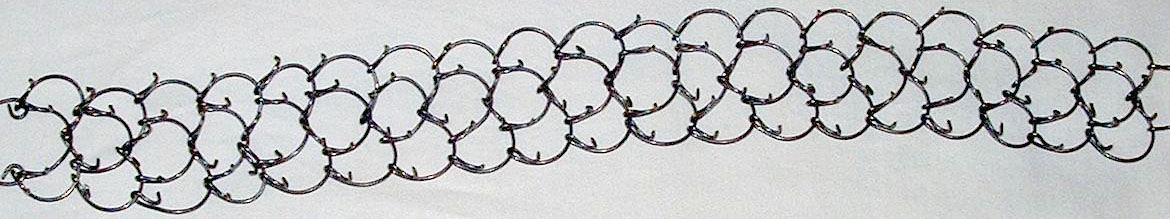

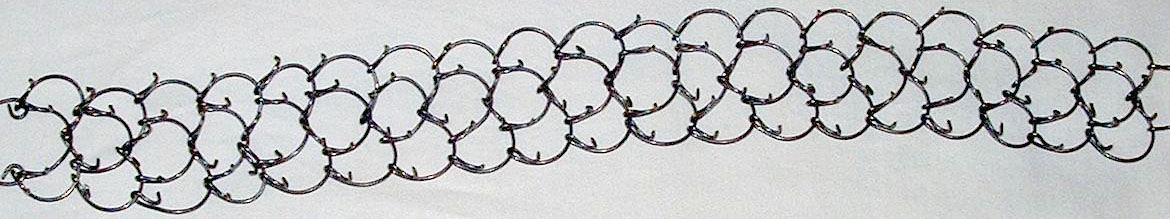

But what really caught my attention was his cilice collection: instruments he used to scratch, flog, and rip his flesh. There was a hair shirt, a rope knout with big, mean knots, and a steel contraption that looked remarkably like a small chain harrow. This last turned out to be worn beneath the shirt, to much the effect you'd imagine.

Later, describing this visit to a close Franciscan friend, I teased him about the equipment I'd seen. Why, I asked, had he never shown me the torture devices he'd been issued on his own ordination?

"Since my brother's day," Pierre answered, "our Order has learned that chasing pain is a waste of time.

"If you just sit quietly and wait, suffering will find you."

(Photos courtesy of Opus Dei Awareness Network [contemporary cilice], Hermann Luyken [Hermano Pedro's tomb and chapel in Antigua, Guatemala], and Wikimedia Commons.)

In the late 40s, a British Colonial Service officer named John Main began to frequent a Malaysian ashram. There, in meditation, the devout Catholic finally tasted his life's ambition: to sit in the presence of God. At length he approached the abbot about converting to Hinduism. The guru's reply astonished him:

"No."

Like most Westerners, Main assumed all religions were about signing people up. But Hinduism (and Zen) actually discourages conversion. One's path is an invaluable, hard-won treasure; throwing it away to start all over again is a bad strategy, if you can help it.

Instead, the guru told Main to find a Christian way of meditation. The idea intrigued the Anglo-Irishman. Was there such a thing? He returned to the UK, became a Benedictine monk, and spent the rest of his life researching and resurrecting a form that had indeed, he discovered, once been central to Christian practice.

As one might imagine, there was some blowback. Notwithstanding Main's watertight historical case – the Desert Fathers, a prominent early Christian lineage, made sitting a pillar of their monastic practice, as did such seminal Church figures as John Cassian and John of the Cross – many insisted that meditation was unChristian by definition, on the well-worn pretexts that "I've never heard of it before" and "non-Christians do it." (For the record, they/we also pray, though I've yet to hear any Christian call down the Lord on prayer.)

Then came 1962. In that year, Pope John XXIII convened his now-famous Concilium Oecumenicum Vaticanum Secundum, otherwise known as the Second Vatican Council. The goal of this historic in-house revolution was to modernise, democratise, and personalise the Church. Main's reconstituted meditation lineage, envisioned as a loose œcumenical affiliation of small, often lay-led groups, fit the bill perfectly. He was given the Pope's blessing and a building in Montréal, and told to make it happen. The result was the World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM), or Christian Meditation for short.

There being no Zen centre nearby when I began my practice, I sat with the local Franciscans, who led a WCCM group, for almost two years. (Nor was I alone; one of my brothers there was a Vajrayana lay practitioner.)

There I discovered that WCCM-model sitting is virtually identical to zazen. A typical weekly meeting starts with a few minutes of teaching from the group leader – generally a brief elaboration on some point of mindfulness, with supporting Bible references – and then a few bars of soothing music, ceding to silence. (Some groups use a Buddhist-style singing bowl instead of music.) Group members repeat the mantra "Maranatha" inwardly, by way of stilling their thoughts and letting God get a word in edgewise. Afterward the music comes back up, or the keisu rings, and meditation ends. There may be shared commentary, or the session may simply disband, amid smiles and "see ya next week"s. The entire ritual takes an hour.

Some groups sit Asian-style, on zafus and zabutons, while others sit on chairs, as mine did. Lotus-sitting groups may follow the Tibetan aesthetic, or Japanese Zen; somewhere there may be a Hindu one. How these matters are decided I don't know, but it's just cosmetic; the practice remains the same.

I remain a major fan of Christian Meditation, and recommend it to the many Christians I meet who voice interest in Zen or meditation. The teaching is indeed œcumenical; there are no specifically Catholic elements in it, and no need for anyone to feel uncomfortable, regardless of denomination. (And you got that from two Buddhists.)

So Christians who hunger for a meditation practice should check out the WCCM. Sadly, there are not as many groups as the lineage deserves, but most large cities have at least one. A good place to start is the WCCM website.

Failing that, contact your local Catholic parish. You might have to insist a little; even among Catholics, Christian Meditation has yet to become a household word. If it turns out there is in fact no group nearby, talk to the priest about starting one. (You don't have to be Catholic to talk to a priest or to ask him for help, yea though Protestant eyes sometimes grow large when I suggest this.)

Any road, if you're looking to "be still and know that I am God", this-here'll get it done.

One of my Franciscan brothers in Québec, a friar named Henri, presented seminars on Christian practice to groups of Catholic seniors – of which he was one. He spoke on many topics, but his most popular lesson began with him passing out polished rocks purchased at the dollar store. He then read the opening verses of John 8 – the oft-quoted and roundly ignored Gospel passage wherein Jesus intervenes in the case of a convicted adulteress, subject under law to death by stoning. "He that is without sin among you," he says, "let him first cast a stone at her." From there Henri brought the teaching forward, pointing out at last that we all possess the Christ-like power of not-throwing.

One of my Franciscan brothers in Québec, a friar named Henri, presented seminars on Christian practice to groups of Catholic seniors – of which he was one. He spoke on many topics, but his most popular lesson began with him passing out polished rocks purchased at the dollar store. He then read the opening verses of John 8 – the oft-quoted and roundly ignored Gospel passage wherein Jesus intervenes in the case of a convicted adulteress, subject under law to death by stoning. "He that is without sin among you," he says, "let him first cast a stone at her." From there Henri brought the teaching forward, pointing out at last that we all possess the Christ-like power of not-throwing.

Henri was a quiet-spoken man, with a gift for landing a point, and he quickly became famous across the province as « le gars qui fait le truc avec les cailloux » ("the guy who does that thing with the rocks"). His main point was that we all carry a rock through this life, and whereas throwing it is a mean and menial act, not-throwing it amounts to a kind of superpower; in a world where we have virtually no agency, we can always do this, to devastating effect. And no-one can stop us.

At the end of the seminar Henri sent everyone's stone home with them, as a reminder of their potential for violence, and their power to contradict it. (On a touching note, some attendees, aware that the Church in Québec is in financial distress, tried to give theirs back, so he could use it in another talk. Henri assured them the Church could still afford rocks, and they'd do greater service to keep it and remember why.)

Proof of Henri's impact came when he encountered former participants, often years later. Many told him they still had their rock, on their dresser, night stand, bathroom or kitchen counter, or dashboard. More than one reached into a purse or pocket and produced the very one; they'd carried it with them everywhere since that day.

I thought then, and I think still, that weaponising not-throwing is a remarkably Zen concept. And so I share it with you today. Indeed, I say we go Henri one better: let us each not-carry a proper Zen stoneless stone through this delusional world, and not-fling it with blockbusting shock and awe at the drop of a hat.

(Photo courtesy of Adrian Pingstone and Wikimedia Commons.)