Wednesday, 30 November 2011

Wednesday, 23 November 2011

WW: November night

Thursday, 17 November 2011

The Capital Punishment Koan

But the good news is I did change my heart. It just took a while to generate the will. And that's my right. I also get better at this stuff. And that's all God asks. Live this moment right; the past is his property. I am no different from everything else: I'm not what I was. And I'm not even what I've done. That was the koan Gautama gave to Angulimala, the serial killer who became his disciple. All you have to do to please God is strive. He accepts all progress, even that which is invisible to others, even that which is invisible to you, as full payment. That's why we live so many lives. In point of fact, we live as many lives as it takes. All of us. No Heart Left Behind. Fudo closes the door on an empty room. That's his vow.

But the good news is I did change my heart. It just took a while to generate the will. And that's my right. I also get better at this stuff. And that's all God asks. Live this moment right; the past is his property. I am no different from everything else: I'm not what I was. And I'm not even what I've done. That was the koan Gautama gave to Angulimala, the serial killer who became his disciple. All you have to do to please God is strive. He accepts all progress, even that which is invisible to others, even that which is invisible to you, as full payment. That's why we live so many lives. In point of fact, we live as many lives as it takes. All of us. No Heart Left Behind. Fudo closes the door on an empty room. That's his vow.And by this truth, capital punishment is not just technically murder, it's the random, joyful murder of serial killers. You never kill the man who killed; every criminal executed is innocent, and that would be the case even if you crucified him the very night. Admittedly, that point is academic. But when you kill a man who has lived twenty more years, suffering in the man-made Hell of prison, you are not only killing a complete stranger, you're often killing a soul seared generous and kind in a fire you set. So don't come snivelling around here with your "eye for an eye;" you've taken a soul for an eye.

Hence the koan of capital punishment: Whose soul have you taken?

Wu Ya's commentary: "Not mine. Anybody missing a soul?"

(Adapted from "100 Days on the Mountain," copyright RK Henderson. Photo courtesy of WikiMedia and Rafael Pi Belda [photographer].)

Topics:

100 Days on the Mountain,

Angulimala,

book,

Buddha,

Christ,

death,

forgiveness,

Fudo Myō-ō,

hermit practice,

karma,

koan,

prisoner,

torture

Wednesday, 16 November 2011

Thursday, 10 November 2011

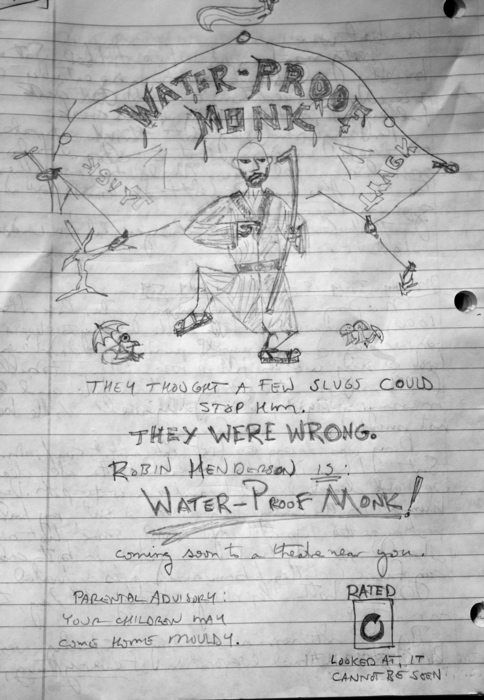

Waterproof Monk

The summer of 2011 was wet in the Willapa Hills. Very wet. And also cold. But mostly wet.

For a monk sitting his 100 Days on the Mountain, sleeping in a cave-like tent and living under a piece of Tyvek, it presented unique challenges. These included, but were not limited to:

- Six-inch banana slugs that got snarled in my robe while I was meditating, then panicked and snotted out a plate-sized patch of slime all over it and my zabuton.

- The same going "squish!" rather dramatically underfoot when I crawled out of bed at 0300 to pee.

- Mildew covering everything, even the nylon effects, stored in my tent.

- The inability to launder clothing or bedding, because I couldn't dry it.

- Bare feet eternally muddy; rain-softened sandals sliding out from under them on any but perfectly level ground.

- And perhaps the worst: being imprisoned in my little jungle clearing, because leaving it meant getting soaked in high grass or brush. (Remember: no drying things.)

A week or so of this, and the Oh-Look-How-Zen-I-Am shtick ceases to umbrella one's morale; one swings from vociferous obscenities to deep depression.

And so it was that I envisioned this movie, starring me as The Nameless Hermit, one midnight while sitting on my sleeping bag under driving rain. If the lines seem a little wobbly, it's because they were drawn by flashlight. Also, the pose was meant to be some kind of scary kung fu stance. Sadly, in the cold light of day, I just look like an angry folk dancer.

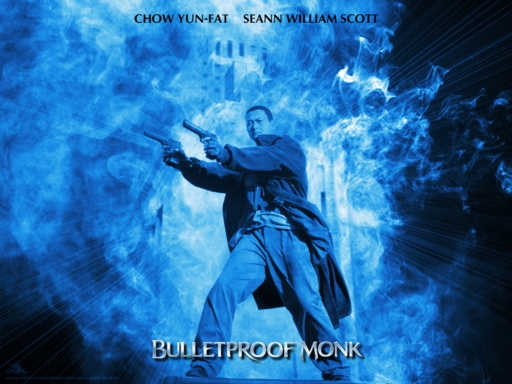

I derived creatively from the Chow Yun-Fat grinder Bulletproof Monk. Of this movie, Chicago Reader film critic Bill Stamets said: "The fight scenes are routine, the humor juvenile, and the Toronto locales rendered drab through muddy cinematography."

So there you go. Change "Toronto" to "North Coast," and you've got my whole life.

So what do you think? Does my movie idea have legs? Frankly, I think I could kick Chow's butt.

Commercially, of course.

|

|

This is exactly what my ango was like. Except I wasn't angry. Or Asian. Or armed. But aside from that, this is exactly what it was like. |

(Adapted from 100 Days on the Mountain, copyright RK Henderson.

Wednesday, 9 November 2011

WW: Vayan con Dios, hermanos

Thursday, 3 November 2011

Good Book: The Zen Path Through Depression

Depression is the elephant in the meditation hall. Virtually all Zenners suffer from it; nobody becomes a monk because he's happy. But Zen has a macho tradition, and since depression is an illness without visible wounds, the old right-wing arithmetic applies:

Depression is the elephant in the meditation hall. Virtually all Zenners suffer from it; nobody becomes a monk because he's happy. But Zen has a macho tradition, and since depression is an illness without visible wounds, the old right-wing arithmetic applies:

machismo + (unauthorised suffering) = rejection.

Thus the institutional response to depressed Zenners ranges from supportive assistance, to conditional acceptance, to outright insult. Students are as likely to be told that they're "attached," that they have the "wrong perspective," or that they're just plain lazy, as to receive useful, scientifically-valid teaching.

In short, depression is our evolution, and our response to it sometimes amounts to creationism: a crap alibi against having to admit that our founders didn't fully understand something.

Fudo-esque confrontation of that heritage is just one strength of Philip Martin's The Zen Path Through Depression. In sensible, measured tones, he accompanies the reader, in the Franciscan sense of the word, through the myriad symptoms of depression: disabling lack of energy; paralysing panic; rumination; pointless rage; guilt and self-recrimination.

Physical symptoms of a disease as physical as diabetes, albeit not yet as well-understood.

I should say that I approached this book with trepidation, and wouldn't have approached it at all if I hadn't been desperate. I had beaten depression with Zen seven years before, and been a monk ever since – it was the first thing I found that could bully the bully.

But two years ago I got nailed again, and this time my Zen practice wasn't up to it. Even admitting that took months. When I finally ordered Martin's book I was afraid I'd either get a pop-psy puff piece with some trendy Zen around the edges, or a traditional Zen treatise that flipped a few koans at me and said, "Stop being depressed."

Happily, what I actually received was a scholarly catalogue of the medical symptoms at one chapter each, along with what modern science knows about their origins. Just that helps a lot, to put things in context and demonstrate that you're neither crazy nor irresponsible. This is followed up by square, monastic-grade Zen analysis of the case.

In essence, Martin says, "This is your mind. This is your mind on depression." And that was as effective as the medication in retuning my mind.

Depression is a lonely hell; shame and embarrassment convince you it's all your fault. Martin proves that it's not. "In our depression," he writes,

…we can start to heal by accepting that a great part of our becoming depressed, as well as much of getting over it, may not be within our control. In doing so, we can let ourselves off the hook, and stop taking the blame.The next move is genius: once his orthodox Zen prescription to accept what is takes the pressure off, he scratches a few questions on the last page of each chapter. You don't have to consider them; only if you want to.

Dig:

Examine your beliefs about suffering. Do you believe it is inevitable? Or that it builds character? Is suffering connected with struggle for you? Would there be no life without suffering?Seems pretty anodyne now, but at the time, with my brain freshly stabilised by a few pills and recharged by Martin's explanations, this stuff was Drano. Note again his classic Zen: no answers. There aren't any wrong thoughts, you just have to be aware of what you're thinking.

Doesn't seem like it would work, but it does. The questions, as much as the teaching, flushed out my system.

It would be hard to imagine a writer better qualified for the job. Martin is a long-time student of Zen; a certified and experienced therapist; and most important, a sufferer of hardcore depression.

This guy doesn’t have a condescending bone in his body. He's a brother.

As the practice began to take, The Zen Path Through Depression felt so good that I started rationing it because I didn't want to run out. When I got low, I would ask myself, "OK, I feel bad, but is it Path-worthy?" And that alone motivated me to endure, to find the strength in my backbone, to haul myself up by my sandal straps.

And pop went the depression.

In the end, with a supportive family, coöperative doctors, my monastic practice, and Martin's book, I got back on my feet. I was even able eventually to stop taking the meds. (But if the depression comes back, I'm back on. Like, now. Don't be afraid of meds, brothers and sisters. They're undramatic drugs, no scarier than aspirin, for a sickness no more imaginary than migraines.)

And while you're up, get a copy of The Zen Path Through Depression. When I needed a lot of help, this book was a lot of help.

Topics:

boat,

book,

depression,

evolution,

Fudo Myō-ō,

hermit practice,

monk,

Philip Martin,

The Zen Path Through Depression,

Zen

Wednesday, 2 November 2011

WW: Demons in the driveway

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)