Showing posts with label forgiveness. Show all posts

Showing posts with label forgiveness. Show all posts

Thursday, 23 January 2025

Hero Practice

They warn you not to meet your heroes,

to leave them unknown quantities,

to avoid disappointment.

But have you considered this:

Meet your heroes.

See them.

Accept their humanity,

the very unremarkable nature of them.

Stare reality in the eye,

that heroes live in this world with us.

They are from here,

made of the same material,

worn by the same forces.

Raised here, hazed here, as convoluted and unsavable as the rest of us.

Penetrate the nature of heroism;

have you run off half-cocked without doing this?

Did your heroes disappoint you?

Or was it you?

(Photo courtesy of Esteban López and Unsplash.com.)

Topics:

advaya,

compassion,

dependent co-arising,

forgiveness,

hermit practice,

mindfulness,

poem

Thursday, 21 November 2024

Koanic Times

In 2022, person or persons unknown outed my article as "hateful", or at least hate-adjacent, whereupon Google fenced it off from search engine indexing and slapped a locked gate on visitors already possessing the link, requiring a second Google sign-in to read it.

This is effectively a take-down, with the added benefit to the taker-down that the piece wasn't literally taken down, perhaps to puncture potential lawsuits.

The whole experience was Orwell-grade surrealism, but I have more important practice, so I posted my mystifiction over it and moved on.

And now it's happened again.

This situation too involves a Nazi reference, but this time the questionable motivation is Facebook's.

Now in the dock: last week's post, consisting of photographic testimony to Nazi vandalism and a call to arms (or at least a proper Zen hell-no) from Canadian literary lion Félix Leclerc.

Facebook's swift condemnation of my anti-Nazism began the instant I posted the link to its server. Within seconds I was informed that it contained offensive content and so had been removed.

This all happened so fast I suspected malfunction, and reposted.

And seconds later, got zapped again.

Given the speed of the response, it's likely that some artificial stupidity-powered hate detector simply saw the swastika and panicked. The boilerplate notice – identical both times – contained a link to something or someone higher up for reconsideration. I immediately complied, certain this possibly human judge would see without difficulty that:

1. The photo documents a criminal act and couldn't possibly be taken for glorification of Nazis or their ambitions, and:

2. The Leclerc quotation below it reflects both the author's and the poster's combative attitude toward totalitarianism and ideologised narcissism.

The next day I received a response, informing me in the same Hal-esque tones that my monkeyshines would remain barred from the service. It too offered further escalation, though frankly, given that my trust in humanity and its instances was exhausted decades ago, I'm just not that invested in it.

Speculation on the origin of such eerie hostility is pointless; the space in which these ghostly arbitrators spin being so far removed from objective reality as to render any attempt to fathom it a waste of time and effort more productively spent on the cushion.

So at the risk of further discipline, let me make my position on the Nazi issue crystal-clear to anyone who might have been disturbed by last week's meditation:

• Nazis are a thing again, and they can be neither ignored nor placated without sacrificing our integrity.

• The global Zen sangha is therefore called to confront them with greater honesty and courage than we did last time.

Because that brought irredeemable shame upon us.

(Photo of 1878 Japanese painting of Fudo Myō-ō, possibly by Kano, courtesy of the Library of Congress and Rawpixel.com.)

Friday, 20 October 2023

The Most Hated Ideology

In 2015 I uploaded a post entitled Forgiveness. It's about forgiveness.

Last year, after almost a decade of being roundly ignored by the Internet, the article was flagged as "sensitive content", fenced behind a warning to visitors, and then a second fence that requires a Google sign-in to pass.

Evidently to shield children from my dangerous advocacy of compassion.

There are times when the irony on this rock gets so thick that one is literally at a loss for words.

Which is why I've haven’t said anything about this until now.

In the article, I point out that I've consistently attracted more mob-borne hatred when advocating for forgiveness than any other topic. By way of example, I cite reactions to a comment I made about Frank Meeink, one-time neo-Nazi who atoned for his hateful conduct and actively defected to the side of kindness and reason. And I wound the thing up with a reference to Angulimala, a figure from the sutras who renounced his career as a serial killer and became a disciple of the Buddha.

I've now re-read Forgiveness half a dozen times, with long periods of reflection between, and still can't find a single line any rational person would call offensive. (It's true I can get, shall we say, "passionate", about certain subjects, nay judgemental in some cases. But unless I'm blind to something, Forgiveness contains no such cases.)

Instead, it appears that someone – or several someones – reported this little-read post from my back-catalogue simply because I advocated mindful compassion toward a repentant Nazi.

More perplexing still, Google also agrees that this is too shocking a contemplation for unsuspecting surfers to stumble across unawares. And much too shocking for kids, under any circumstances.

So, hey. I've been wrong before. If any readers game enough to breech the safety fences could read the text behind them and explain to me where you find offence, I would be sincerely grateful.

Please post your thoughts in the comment section below, if you don't mind. My word that I'll be equanimous toward all, pro- or anti-Ring, that are on-topic and not personally abusive to anyone.

Because I think the Great Sangha needs to start talking about this forgiveness thing.

(Photo courtesy of Damian Gadal and Wikimedia Commons.)

Last year, after almost a decade of being roundly ignored by the Internet, the article was flagged as "sensitive content", fenced behind a warning to visitors, and then a second fence that requires a Google sign-in to pass.

Evidently to shield children from my dangerous advocacy of compassion.

There are times when the irony on this rock gets so thick that one is literally at a loss for words.

Which is why I've haven’t said anything about this until now.

In the article, I point out that I've consistently attracted more mob-borne hatred when advocating for forgiveness than any other topic. By way of example, I cite reactions to a comment I made about Frank Meeink, one-time neo-Nazi who atoned for his hateful conduct and actively defected to the side of kindness and reason. And I wound the thing up with a reference to Angulimala, a figure from the sutras who renounced his career as a serial killer and became a disciple of the Buddha.

I've now re-read Forgiveness half a dozen times, with long periods of reflection between, and still can't find a single line any rational person would call offensive. (It's true I can get, shall we say, "passionate", about certain subjects, nay judgemental in some cases. But unless I'm blind to something, Forgiveness contains no such cases.)

Instead, it appears that someone – or several someones – reported this little-read post from my back-catalogue simply because I advocated mindful compassion toward a repentant Nazi.

More perplexing still, Google also agrees that this is too shocking a contemplation for unsuspecting surfers to stumble across unawares. And much too shocking for kids, under any circumstances.

So, hey. I've been wrong before. If any readers game enough to breech the safety fences could read the text behind them and explain to me where you find offence, I would be sincerely grateful.

Please post your thoughts in the comment section below, if you don't mind. My word that I'll be equanimous toward all, pro- or anti-Ring, that are on-topic and not personally abusive to anyone.

Because I think the Great Sangha needs to start talking about this forgiveness thing.

(Photo courtesy of Damian Gadal and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

Angulimala,

Buddha,

Buddhism,

compassion,

forgiveness,

hermit practice

Thursday, 27 July 2023

The Gift of Ingratitude

I talk a lot about gratitude on this channel. It's a habit that has two not-very-subtle origins:

1. Gratitude is the wheel of morality, andPrior to becoming a hermit monk, I was routinely guilty of chronic ingratitude. Which is why I'm always urging everybody else to be more grateful.

2. I'm not grateful by nature.

The problem with such haranguing is that it presupposes others need to be so harangued. Few things are as infuriating as being lectured by some freelance supervisor not to do a thing you were in no wise going to do in the first place. Prejudice that lacks the patience even to wait for you to fall into its trap is the worst of a filthy tribe.

But there's an even better reason not to invade this angel-forsaken terrain on a gratitude warrant: like so many other platitudes, it just wounds the wounded again. Now you're not only in pain, you're selfish and stupid besides.

Which is why I found this counsel particularly powerful:

"Please take this as permission to treat certain periods of your life as an unholy free-for-all during which you are not obligated to feel grateful."The writer is American advice columnist Carolyn Hax, whose feature I encountered in a random newspaper.

Her correspondent was hoeing a particularly difficult row, and feeling guilty for undervaluing aspects of her existence that weren't damnably awful at that moment.

And Ms. Hax nailed it: you don't lose the right to resent intrusion on your peace just because other aspects of your life haven't.

I'm reminded of a period when I was badly injured by a calculating individual who left me crippled and broken. Even in distress I was aware that the damage had come largely with my own consent. (Pro tip: sociopaths usually lead their marks down an entangling trail of agreements, resulting in at least partial condemnation of their victims by the public when they at last drop the hammer. That's what they get off on.)

In his awareness that I could have avoided this, the abbot in my head kept disallowing my feelings of anger and offence. But at last I realised that this is what anger and offence are for. Misplaced they're a failing, but when justified, a critical source of truth and self-preservation.

I still remember the moment we talked this over, the abbot and I, and agreed that the time had come to let the dogs off the leash. What happened next is a tale for another time, but the spoiler is that I got the needed results. Taking umbrage under the watchful eye of my mindfulness practice was tremendously empowering, at a time when I felt wholly disabled, and ultimately made me a better person.

Memories that Ms. Hax's advice triggered. Because gratitude, acceptance, atonement, and other moral imperatives aren't absolutes. Like everything else, they exist within the great matrix of circumstance that comprehends everything in existence.

So there are in fact times when gratitude, like forgiveness and generosity, is not only optional, but pathological. The confines of this phenomenon are limited; no ground to stop being grateful as a whole. But for a year or two, in a specific context, till you regain a measure of largesse?

No more Goody Two-Shoes.

(Guard dog sculpture courtesy of Jason Lane; photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photgrapher.)

Thursday, 24 March 2022

Higher Ground

I'd been a hermit monk for 5 years when I heard on my truck radio that after the news the host would speak with a US Army chaplain just back from Iraq.

I have a tetchy relationship with military chaplaincy. At best it enables sin. At worst it weaponises it. None of the planet's mainstream religions endorse collective destruction, no matter how vociferously their institutions argue otherwise.

On the other hand, the war industry mass-produces humans badly in need of refuge, which makes military chaplains a very good thing. It's just that I doubt that's the reason they were commissioned. But some do it anyway – help the exploited survive hell – even though it contradicts the larger mission, which is to exploit those people

Still, when the radio presenter announced her upcoming guest, I instinctively moved to change stations.

Then I thought, hold on. Don't I sell myself as a Zen monk? Haven't I taken a precept to strive after an ideal that rejects otherness and recognises that we're all the product of forces beyond our control?

Haven't I myself committed acts of great hypocrisy? And aren't I now poised, finger on trigger, to commit another one?

Bodhisattvas test your sincerity before they offer their gifts.

So I stood down. If this guy started selling partisan pap, I could always press the scan button later.

And that's how I received one of the central tenets of my monastic practice.

In the interview, the officer was asked for an example of the sort of ministry he provided. He related the story of a young soldier who came to him after smashing into a private Iraqi home and spraying the entire weeping family with automatic weapons fire

As they huddled on the floor of their own living room.

It's to the young man's enduring credit, and that of those who raised him, that this atrocity took him to the brink of suicide. Decent people aren't able to do this sort of thing. No matter what kind of clothes they're wearing or what they've pledged to whom.

This one couldn't stop putting himself in the place of that Iraqi father. Seeing himself through his target's eyes. The complete absence of justice or justification. Who he was in that scenario

Ha!, thought I. Get yourself out of this one, warrior preacher.

The chaplain's response was notable first for what he didn't say. He didn't talk about orders, patriotism, or service. He didn't present excuses or greater-good defences, or displace blame onto the soldier's government or superiors. There were no references to geopolitics or God's will.

He simply asked the broken man what his victim's duty was.

I can imagine the man was taken aback. I certainly was.

"If matters had been reversed," said the Army chaplain, "and he'd killed your family, what would your duty to him be?"

"I… I guess, to forgive him," the soldier stammered.

"Then that's his duty to you as well."

I've been meditating on this koan ever since.

We're taught early on that forgiveness is next to godliness, that we must do it. And that's certainly correct.

But what we're not told is that we also have a right to demand it. Because it's also everybody else's unshirkable responsibility. This was the Buddha's teaching to Aṅgulimāla: when you're no longer the person who committed the crime, atonement, not condemnation, is your burden.

I'll warrant readers who were offended by my criticisms of military chaplains are little mollified by my chastened gratitude to this one for his insight.

But I suspect the man himself will forgive me.

Deep bow to all who labour honestly for higher ground.

(Photo of US Army Buddhist Chaplain insignia courtesy of Ingrid Barrentine, the Northwest Guardian newspaper, and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

advaya,

Angulimala,

bodhisattva,

Buddha,

Christianity,

forgiveness,

hermit practice,

non-hypocrisy,

suicide

Thursday, 26 March 2020

Good Song: Don't Judge a Life

If you don't know John Gorka, you should know John Gorka.

Few artists sing the human heart like John. A number of his songs sum up affecting moments of my life in ways that not only people my isolation, they help me understand what happened.

But in this case he's addressing a wider problem. The immediate topic is fellow poet and good friend Bill Morrissey, who possessed much the same gift as John's, had much the same sort of career – ignored by the machine, adored by initiates – and died in 2011 from complications of a dissolute life.

An Amazon reviewer who knew Bill quoted him from a conversation they'd had:

"Most everybody knows that I've had some rough sledding for the last few years, including my well-known battle with the booze. A couple of years ago I was diagnosed as bipolar and I am on medication for depression, but sometimes the depression is stronger than the medication.And then he was gone.

"When the depression hits that badly, I can't eat and I can barely get out of bed. Everything is moving in the right direction now, and throughout all of this I have continued to write and write and write."

Don't Judge a Life – bookend to Peter Mayer's Japanese Bowl, spinning the issue from first to second person – is a reminder we all need on a daily basis. I particularly like this part:

Reserve your wrath for those who judgeReaders with a solid base in Christian ethics will instantly recognise the source of this counsel. The same precept in the Buddhist canon is a little less explicit, but our teachings on bodhisattva nature clearly endorse and require it.

Those quick to point and hold a grudge

Take them to task who only lead

While others pay, while others bleed

And both faiths stand firmly on the last verse.

DON'T JUDGE A LIFE

by John Gorka

Don't judge a life by the way it ends

Losing the light as night descends

For we are here and then we're gone

Remnants to reel and carry on

Endings are rare when all is well

Yes and the tale easy to tell

Stories of lives drawn simplified

As if the facts were cut and dried

Don't judge a life as if you knew

Like you were there and saw it through

Measure a life by what was best

When they were better than the rest

Reserve your wrath for those who judge

Those quick to point and hold a grudge

Take them to task who only lead

While others pay, while others bleed

Tapping the keys in a life of rhyme

Ending the tune and standard time

Silence fills the afternoon

A long long way to gone too soon

Don't judge a life by the way it ends

Losing the light as night descends

A chance to love is what we've got

For we are here and then

We're not

(Photo courtesy of Jos van Vliet and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

addiction,

Bill Morrissey,

bodhisattva,

Buddhism,

Christianity,

depression,

empathy,

ethics,

forgiveness,

hermit practice,

John Gorka,

music,

Peter Mayer,

review,

video

Thursday, 7 March 2019

Hindsight

I was difficult when I was younger.

Part of me would like to go back and face some of those challenges and circumstances again, except... not be a jerk this time. Think it might help?

"Not making a bad situation worse." Right up there with "being grateful for your blessings", and "cherishing other people just because they're in the boat with you."

Lessons it took me longer than most to learn.

(Photo courtesy of Jonny Keicher and Unsplash.com.)

Topics:

ahimsa,

blessing,

compassion,

dependent co-arising,

empathy,

forgiveness,

generosity,

gratitude,

hermit practice,

love,

mindfulness,

reconciliation

Thursday, 24 January 2019

Lynch's Law

An old friend last week posted a link to The Cruelty of Call-Out Culture: How Not To Do Social Change, David Brook's timely and incisive denunciation of our current lynch-mob fad. (The link goes to the original NYT post, which may not be available to all. Sadly I was unable to find an unregulated source.)

An old friend last week posted a link to The Cruelty of Call-Out Culture: How Not To Do Social Change, David Brook's timely and incisive denunciation of our current lynch-mob fad. (The link goes to the original NYT post, which may not be available to all. Sadly I was unable to find an unregulated source.)In it, Brooks relates a recent NPR segment on two members of the punk scene who were tarred and feathered (virtually, so far), then shunned, utterly and irrevocably, by their erstwhile comrades.

The first target, best friend of one Emily, was accused of "sending […] an unwelcome sexually explicit photograph" to a woman Emily apparently didn't know. Emily instantly turned on him, intentionally busted up the man's circle of friends, and effectively destroyed his life. She's had no further contact with this professed "best friend" since.

And then Emily herself was called out, in her case as a one-time cyber bully, having among other things posted a piling-on emoji to an Internet thread mocking a classmate. More than ten years previous. When she was in high school.

She instantly came in for the Adulterer's Special in her own right and was shunned in turn, as deeply and implacably as her apparently irredeemable former friend, by the same crowd she too regarded and depended upon as family.

At this point some may repress a smirk, but it turns out putting folks' eyes out ain't all that tidy, droogies. Witness:

"[Emily's accuser said the act of denouncing her] gave him a rush of pleasure, like an orgasm. He was asked if he cared about the pain Emily endured. 'No, I don’t care,” he replied. […] I literally do not care about what happens to you after the situation. I don’t care if she’s dead, alive, whatever.'"Let's be clear. In this man's view, death is a reasonable punishment for flippancy. I think the moral here is, vet your allies carefully.

In further justification of his aggression, this individual declares that he was physically and emotionally abused in the past. In response to which my Zen training has taught me to ask: "By her?"

I'll warrant the reply to that one is less erotic.

Although by Emily's figuring she made moral progress between her bitchy teenage years and conscientious adulthood, let's note that her actions at both ages were identical: flush a pariah and move in for the kill.

Perhaps most frightening of all, she even condones her own attackers' behaviour, accepting the Gandhic hotbox she helped build as a righteous reaction to her ostensibly inexpungeable crimes. In other words, it seems she has gained little insight from all of this. She's suffered, deeply and grievously, for nothing.

Which is my definition of hell.

As for her tormentor's delusions, let's crack those right now: victims of injustice are more responsible for their actions, not less. Far from green-lighting cruelty, survival obliges you to stand firmly and publicly against the megalomania and mindless brutality that brutalised you. Particularly when it metasticises into an untargetted orgy.

Some commenters to the article claimed that vigilantism is righteous because duly constituted authority has long ignored, condescended to, even criminalised the victims of social crimes. Basically, "bullies must be bullied because bullies won't bully the bullies who bully the bullies I bully."

Now there's a koan. But the Buddha already solved this one for us, 2500 years ago:

"Blood stains cannot be removed by more blood. Resentment cannot be removed by more resentment."That there's a paucity of justice in this lazy world is woefully clear. That we can secure it by further injustice is the con of a grifter.

Due process and calm analysis – of everything, including intent and context – are the right and left hands of justice. And empathy is its brain. If after patient and thorough investigation a case turns up weak, the accused is usually innocent, at very least of the precise charge or degree. As unsatisfying as that is to those who burn for payback, there is no other route to a just society.

If justice is truly your goal, you have to get off the sofa and build a system that values and compels it. Which is exceedingly difficult to do. But anything less just triples the injustice.

Bottom line: the karmic benchmark here remains the same it's always been: "Am I different from my enemies? Do I eliminate suffering, or create it?"

It's a tough inquisition, and one I freely own I fail on a regular basis.

But it simply will not do to skip it.

(Graphic courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Thursday, 24 May 2018

Good Story: To See the Invisible Man

"And then they found me guilty."

I've been meaning to post on this found teisho since I launched Rusty Ring, away back in the Kamakura Period. Somehow I always found a reason not to; afraid to cock it up, I imagine. But conditions have conspired to kick me into gear.

It seems we've entered the Age of Vengeance, wherein no limitation on the godlike All-Seeing I will be endured. Both Right and Left are stomping about, meting out "justice" from a position of self-declared moral superiority, yet in style remarkably similar to a pogrom. (And also to each other. Here's a koan: if you must become your enemy to defeat him, can you?)

As for insight; empathy; forgiveness; compassion; the instinctive restraint that governs men and women of good faith…

Get a rope.

In such times, a hermit monk could do worse than invite his brothers and sisters To See the Invisible Man.

Robert Silverberg's seminal contemplation on the nature of true decency first appeared in the inaugural (April 1963) issue of sci-fi pulp Worlds of Tomorrow. I became aware of it in 1985, when it was faithfully adapted for the first revival of Rod Serling's Twilight Zone.

For those 20-odd minutes I was riveted to the television; though still in my early 20s, I'd lived enough to recognise the unflinching truth Silverberg was burning into my screen. It's nothing less than a Jataka Tale on the gulf that separates bourgeois morality from the real thing.

In this case, we have a man sent up the river for the crime of "being an arsehole". (No wonder Silverberg's utopian society has done away with prisons; with laws like that, there'd have to be one on every block.)

Will their ingenious, diabolic alternative sentence turn this egocentric bastard into a productive citizen? You'll have to see it to find out.

At this writing, two uploads of the Twilight Zone segment are available on YouTube:

The entire series is also available on DVD.

With track records like these, and any good luck, you'll be able to find at least one of them. The writing, performances, and direction are all excellent. Allowance allowed the changing norms of television production, it's aged very well.

If on the other hand you prefer to read the original, then by truly miraculous wrinkle of the Enlightenment Super-Path:

For the rest, I'll leave you with my war cry:

"That which does not kill me, makes me kinder."

It's a simple insight that I realised soon after I become a monk.

It also explains why my own society frequently hates me.

(Mad-scientist chortle.)

(Photo from a screen-cap of the Twilight Zone episode.)

I've been meaning to post on this found teisho since I launched Rusty Ring, away back in the Kamakura Period. Somehow I always found a reason not to; afraid to cock it up, I imagine. But conditions have conspired to kick me into gear.

It seems we've entered the Age of Vengeance, wherein no limitation on the godlike All-Seeing I will be endured. Both Right and Left are stomping about, meting out "justice" from a position of self-declared moral superiority, yet in style remarkably similar to a pogrom. (And also to each other. Here's a koan: if you must become your enemy to defeat him, can you?)

As for insight; empathy; forgiveness; compassion; the instinctive restraint that governs men and women of good faith…

Get a rope.

In such times, a hermit monk could do worse than invite his brothers and sisters To See the Invisible Man.

Robert Silverberg's seminal contemplation on the nature of true decency first appeared in the inaugural (April 1963) issue of sci-fi pulp Worlds of Tomorrow. I became aware of it in 1985, when it was faithfully adapted for the first revival of Rod Serling's Twilight Zone.

For those 20-odd minutes I was riveted to the television; though still in my early 20s, I'd lived enough to recognise the unflinching truth Silverberg was burning into my screen. It's nothing less than a Jataka Tale on the gulf that separates bourgeois morality from the real thing.

In this case, we have a man sent up the river for the crime of "being an arsehole". (No wonder Silverberg's utopian society has done away with prisons; with laws like that, there'd have to be one on every block.)

Will their ingenious, diabolic alternative sentence turn this egocentric bastard into a productive citizen? You'll have to see it to find out.

At this writing, two uploads of the Twilight Zone segment are available on YouTube:

- an integral print over Spanish subtitles has survived there since 2015

- and dendrochronology pins this old-style three-parter all the way back in 2008 CE.

The entire series is also available on DVD.

With track records like these, and any good luck, you'll be able to find at least one of them. The writing, performances, and direction are all excellent. Allowance allowed the changing norms of television production, it's aged very well.

If on the other hand you prefer to read the original, then by truly miraculous wrinkle of the Enlightenment Super-Path:

- the entire April '63 issue of Worlds of Tomorrow is freely available in ebook form, or...

- if you'd rather have just the text, the Ru-net offers it here.

For the rest, I'll leave you with my war cry:

"That which does not kill me, makes me kinder."

It's a simple insight that I realised soon after I become a monk.

It also explains why my own society frequently hates me.

(Mad-scientist chortle.)

(Photo from a screen-cap of the Twilight Zone episode.)

Topics:

compassion,

empathy,

forgiveness,

justice,

movie,

review,

Robert Silverberg,

Rod Serling,

Twilight Zone

Thursday, 8 February 2018

You Damn Well Can Do Something About It

This week I encountered a piece of apparent fluff from The Stranger, Seattle's edgier (or maybe just more sophomoric) alternative newspaper. And as often happens in The Stranger, it turned out to be hard-hitting insightful fluff.

A Playlist for the Brokenhearted is a Valentine's Day laundry list of good hurtin' songs for the damaged, courtesy of Sean Nelson. (By the way, Sean, if you see this: pretty much the entire Magnetic Fields catalogue. Not just Smoke and Mirrors. I Don't Want to Get Over You. I Don't Believe You. You Must Be Out Of Your Mind. I Don't Believe in the Sun. Seriously. Throw a dart.)

Seems like a throwaway premise, until you start the half-page preamble, which turns out to be an extended Zen contemplation on a "little morsel of non-insight" that crushed people are often thrown:

"The past is past. Nothing you can do about it now."

Regular readers know that facile responses to suffering are one of my detonators. And the writer goes on to vivisect this one with literary power, even citing at one point an early work by Alan Watts. (Is Nelson a Zenner? He writes like one. Not a Baby Boomer Western Zen "When Things Fall Apart" mandarin, but a gritty younger guru-sceptic "Hardcore Zen" type, from our invisible-but-still-next generation.)

The text amounts to a didactic consideration of the philosophical ramifications of love – something the Buddha suggested we'd be better off just not doing. But we're gonna do it, since it's our nature. It's also about forgiveness – of others, of ourselves, of love itself. To which end he offers his mixtape, as a means to revisit and reanalyse the reader's specific train wreck.

So I'll just let you savour it yourself. There's much to appreciate, even if the playlist itself turns out to be beyond your tastes or knowledge. (Again, you'll find the Stranger article here.)

In the meantime, I'd like to drop a bomb of my own:

You damn well can do something about it.

As William Faulkner famously said, "The past isn't dead. It isn't even past."

Yeah, the events – and often the people – that hurt you have fled into the past, where you can't reach them.

But the suffering is right here and right now. Where you can totally kick its butt.

The fact that Zen is all about here and now leads some to imagine it means ignoring the wrongs and wounds of the past; to insist they're not alive, not important, not still banging around out there causing suffering in all directions.

If that were so, Zen would be a pointless New Age pipe dream.

So let me be perfectly clear: you damn well can do something about the pain, regardless of what caused it or when. You can make it bearable, which is the same as declawing it. You can even turn it into insight, forgiveness, fulfilment, contentment. And in a very concrete sense, you can go back into the past, to the place where the past lives, and pull it out by the roots.

Many paths will take you there, but I advocate zazen as a good start and the foundation of a lifetime practice.

I also advocate Zen and Buddhist insight into the origin and nature of emotional pain.

Most of all, I advocate awakening to the fundamental nature of reality and our own existence.

It works.

Peace and progress to all brother and sister seekers.

(Art from Sean's article in The Stranger.)

A Playlist for the Brokenhearted is a Valentine's Day laundry list of good hurtin' songs for the damaged, courtesy of Sean Nelson. (By the way, Sean, if you see this: pretty much the entire Magnetic Fields catalogue. Not just Smoke and Mirrors. I Don't Want to Get Over You. I Don't Believe You. You Must Be Out Of Your Mind. I Don't Believe in the Sun. Seriously. Throw a dart.)

Seems like a throwaway premise, until you start the half-page preamble, which turns out to be an extended Zen contemplation on a "little morsel of non-insight" that crushed people are often thrown:

"The past is past. Nothing you can do about it now."

Regular readers know that facile responses to suffering are one of my detonators. And the writer goes on to vivisect this one with literary power, even citing at one point an early work by Alan Watts. (Is Nelson a Zenner? He writes like one. Not a Baby Boomer Western Zen "When Things Fall Apart" mandarin, but a gritty younger guru-sceptic "Hardcore Zen" type, from our invisible-but-still-next generation.)

The text amounts to a didactic consideration of the philosophical ramifications of love – something the Buddha suggested we'd be better off just not doing. But we're gonna do it, since it's our nature. It's also about forgiveness – of others, of ourselves, of love itself. To which end he offers his mixtape, as a means to revisit and reanalyse the reader's specific train wreck.

So I'll just let you savour it yourself. There's much to appreciate, even if the playlist itself turns out to be beyond your tastes or knowledge. (Again, you'll find the Stranger article here.)

In the meantime, I'd like to drop a bomb of my own:

You damn well can do something about it.

As William Faulkner famously said, "The past isn't dead. It isn't even past."

Yeah, the events – and often the people – that hurt you have fled into the past, where you can't reach them.

But the suffering is right here and right now. Where you can totally kick its butt.

The fact that Zen is all about here and now leads some to imagine it means ignoring the wrongs and wounds of the past; to insist they're not alive, not important, not still banging around out there causing suffering in all directions.

If that were so, Zen would be a pointless New Age pipe dream.

So let me be perfectly clear: you damn well can do something about the pain, regardless of what caused it or when. You can make it bearable, which is the same as declawing it. You can even turn it into insight, forgiveness, fulfilment, contentment. And in a very concrete sense, you can go back into the past, to the place where the past lives, and pull it out by the roots.

Many paths will take you there, but I advocate zazen as a good start and the foundation of a lifetime practice.

I also advocate Zen and Buddhist insight into the origin and nature of emotional pain.

Most of all, I advocate awakening to the fundamental nature of reality and our own existence.

It works.

Peace and progress to all brother and sister seekers.

(Art from Sean's article in The Stranger.)

Topics:

Alan Watts,

Buddha,

Buddhism,

depression,

forgiveness,

hermit practice,

love,

meditation,

music,

Philip Martin,

review,

Sean Nelson,

Seattle,

The Magnetic fields,

The Stranger,

Valentine's Day,

William Faulkner,

Zen

Thursday, 17 November 2016

Tough Love

Once, when I was in Grade 2, my teacher had all of us save our milk carton from lunch. Afterward we folded it into a flower pot, filled it with dirt, and planted a single bean in it. Then we lined up our little pots on the windowsill and waited.

Once, when I was in Grade 2, my teacher had all of us save our milk carton from lunch. Afterward we folded it into a flower pot, filled it with dirt, and planted a single bean in it. Then we lined up our little pots on the windowsill and waited.To nobody's surprise, within a week each had produced a shoot. Our teacher then divided us into groups and issued new orders. Group Number 1 got to leave their bean plants in the sun and care for them as usual, but everyone else had to stop watering theirs, relocate it to a closet, sit it on the radiator, or the like.

I was ordered to put mine in the refrigerator.

What happened next remains as vivid to me as this morning.

I have a loving, if independent, nature, and in the few days I'd been tending it I'd conceived an affection for the bright green tendril striving upward. I also wasn't a moron. What seven-year-old doesn't know what happens to a living thing in the faculty room fridge? Years later, as a teacher myself, I could have prepared a better lesson plan than that during passing period. Using nothing more than what I had in my desk.

On a Friday afternoon.

I hung back as the rest of my group came forward, hoping she wouldn't tally us. But she did.

"Robert?" she demanded. "Where's Robert? Don't you have a plant?"

I mumbled the affirmative.

"Bring it here."

I hesitated, carton in hand.

"Do you hear me? Bring it here."

"But…" I stammered, barely audible. "I don't want to kill it."

"What?" she snapped, incredulous.

I raised my eyes.

"I don't want to kill it."

At this point my teacher pitched what can only be called a power tantrum. "Oh, I see!" she snarked, enraged beyond self-respect. "Everyone else is participating, everyone else has to do what they're supposed to, but Robert (her voice dripped) doesn't want to kill his!

"Everybody look at Robert! He's not like us! He's special!"

I began to sob, and she continued to demonstrate why I have so little respect for authority. (And possibly why my attitude toward women was for so long uncharacteristically hostile.)

"You put that bean plant on the cart THIS INSTANT!" she commanded.

I did. But I didn't stop crying for some time.

Half a century later, I'm just starting to catch a whisper of public commentary about the state of empathy on this backwater planet. Not much. Not enough. But a few writers, here and there, are beginning to question the fitness of our souls to ensure our continued survival.

Empathy is the defining human strength, the single advantage that pushed our fangless, clawless arse to the top of this heap.

But we have a knotty relationship with the stuff of our success. The "toughness" and "courage" we admire in leaders and ourselves amounts most often to cruelty, self-centredness, and indifference. Those who betray a glimmer of "weakness" – empathy, compassion, sophistication, humanity, evolutionary superiority – are abused and ridiculed. The rest of us are conditioned to look on silently.

Which is why empathy needs claws and fangs.

In my life I've consistently been punished more severely for empathy than for cruelty. When guilty of the latter, I've been disciplined; when the former, I've been humiliated, ejected, and blacklisted.

Therefore, it's increasingly critical that decent, fully-evolved human beings learn the difference between insensitivity and just pissing others off. We must refuse to pipe down when advocating forgiveness, generosity, and the objective analysis of karma, regardless of sneers and threats. The alternative is what we already have, what's killing us progressively faster: government by the least human. Whether national, local, or in some grade school classroom.

Most importantly, we must actively patrol the state of empathy in our communities, and teach future generations to honour and protect their own evolved souls and defend those of others.

So check it out, bitch: this entire species depends on the beans we produce.

Stand aside, please.

(Adapted from Growing Up Home, copyright RK Henderson. New Life [photo] courtesy of Juanita Mulder and Pixabay.com.)

Topics:

compassion,

empathy,

evolution,

forgiveness,

generosity,

Growing Up Home,

hermit practice,

karma,

love

Thursday, 3 November 2016

Penance

Some time ago I had the good fortune to spend a month in Guatemala. While in the ancient capital I visited the tomb of Hermano Pedro, a Franciscan saint who looms large in the faith and history of that country.

Preserved there is Pedro's old cell, wherein visitors can meditate on the meagre possessions of a man who gave his life to advocating for and serving the poor. It boils down to one change of clothing; a chair and a walking stick; a bed sheet and sundry devotional items; and a human skull, used by Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu monastics in times past to keep their head in the game, so to speak.

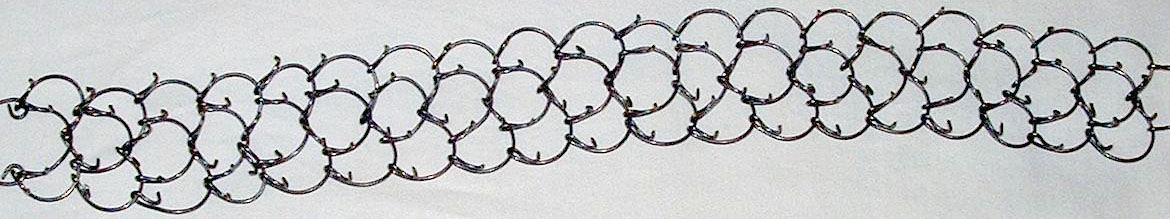

But what really caught my attention was his cilice collection: instruments he used to scratch, flog, and rip his flesh. There was a hair shirt, a rope knout with big, mean knots, and a steel contraption that looked remarkably like a small chain harrow. This last turned out to be worn beneath the shirt, to much the effect you'd imagine.

Later, describing this visit to a close Franciscan friend, I teased him about the equipment I'd seen. Why, I asked, had he never shown me the torture devices he'd been issued on his own ordination?

"Since my brother's day," Pierre answered, "our Order has learned that chasing pain is a waste of time.

"If you just sit quietly and wait, suffering will find you."

(Photos courtesy of Opus Dei Awareness Network [contemporary cilice], Hermann Luyken [Hermano Pedro's tomb and chapel in Antigua, Guatemala], and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

Buddhism,

Christianity,

dukkha,

forgiveness,

Franciscan,

Hermano Pedro,

hermit practice,

monk,

torture

Thursday, 13 October 2016

Generosity Meditation

Try this:

- Name the virtue that's the basis of all human morality.

- Which fundamental virtue is seldom discussed, never identified as a moral or social imperative, never urged on children, never used to shame leaders?

PSYCH! They're one and the same.

We endure a lot of banging on these days about "truth". It's one of the most popular Twitter hashtags, and the worst thing a candidate can be accused of not having. A whole tribe of conspiracy freaks are called "truthers"; another of protesters relentlessly "speaks truth to power".

And how about this gem from my Internet games collection: Google the string "truth about" (with quotation marks). Then binge on thousands upon thousands of pages wherein CRAP! is repeatedly DEBUNKED! by thousands of EXPOZAYS! of everything from GUNS! to EGGS!!!

Truth is a weapon-word. It can be wangled and pounded into any shape, and then used to bludgeon your enemies ad infinitum. By contrast, generosity makes a punky cudgel at best. Observe:

- "I say before all of you today, that my opponent is demonstrably UNGENEROUS!" (Such a broadside will probably send her more votes than it subtracts.)

- "The proposed legislation is of unprecedented generosity." (Can you hear the chorus of consternation?)

- "You should take anything my ex says with a grain of salt. Generosity is not his strong suit." (Admit it; you immediately took this as a confession of guilt on the part of the speaker.)

We don't just ignore generosity; we actively discourage it. Torture became a proud part of Western democracy on the insistence that we can no longer afford to be generous. Critics of the Black Lives Matter movement deplore the generosity that slogan implies. At base, the American obsession with firearms is about an alleged right to be ungenerous. "Vex me and I'll shoot you."

Health care, refugees, economic policy, welfare, education, criminal justice, immigration… every bone of contention before us today rests on the assertion that generosity is a character flaw.

It is not. Generosity is in fact the highest expression of evolution, the mother of all virtues. It's the origin of forgiveness, and the rationale for acceptance. Generosity makes us human – or not. None of its army of antonyms – stinginess, greed, vengeance, legalism, self-centredness, judgment, cowardice, indifference, narrowness, materialism, shallowness, hostility, bigotry, triumphalism, stubbornness – are counted strengths. At least not when called by name.

Therefore, as is my habit, I've worked up a meditation to discipline my monkey mind (which truthfully amounts to a sasquatch mind) to remain alert to the state of generosity in my life and actions. Thus:

- How generous are the propositions of this speaker, this scholar, this candidate?

- How generous is this religious teaching?

- How often do I suggest generosity to those younger? (If you're a parent: how often do you advise your kids to be generous? How often do I demonstrate it?)

- How often do I pronounce or write the words "generosity" and "generous"?

- How often do I use the word "ungenerous" in argument, and defend it when sneered down?

- How often did I reconsider my actions today, in light of generosity?

- To whom was I more generous: strangers, or friends and family? (You'll find it's usually the former. Is this moral, or even logical?)

- What did I give today? (If, like me, your day often includes little human contact, then what did I give to plants and animals, or humanity, or myself?)

- Did I give anything I didn't initially want to give? Did I only give things I was prepared to part with?

And so on.

Lakota scholar Luther Standing Bear, assessing the moral worth of the nation-state, concluded: "Civilisation has been thrust upon me… and it has not added one whit to my love for truth, honesty, and generosity."

My experience (minus the thrusting) has been identical. Henceforward I'm making generosity a conscious, deliberate part of my monastic practice, both in what I expect of myself, and how I measure others.

(Prince Vessantara Gives Away His White Elephant, from the Vessantara Jataka, courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

acceptance,

forgiveness,

game,

generosity,

hermit practice,

meditation,

The Rusty Ring Art Gallery,

torture,

Zen

Thursday, 24 March 2016

The 1 Habit of Truly Decent People

We're hearing a lot these days about patriotism and national greatness and ideological purity and economic theory and cold dead fingers. The speakers seem to take it for granted that their convictions are honourable, simply because they are convictions.

I've encountered this misconception again and again in my half-century walkabout, first as a historian and then as a religious man. Faith is sexy. It's dramatic and macho and you get to make stirring speeches with lots of sanctimonious platitudes, like a movie hero.

But take it from me: given enough indulgence and half a chance, believers will destroy the world.

Just being embattled doesn't confer honour. Bad causes are a giant waste of time and life, to say nothing of the mountain of karmic debt. Shall we free-associate a few examples?

Yet people continue to insist they can skip the humility, self-examination, and moral courage required of competent adults, and make a thing right by sheer force of conviction.

I know what that's like. I was a revolutionary myself. I clung tightly to a list of high-minded principles. That made me angry, which I took for a mark of righteousness. And that anger made me hypocritical, untrustworthy, and ultimately counter-revolutionary. I could – and did – turn on others for the slightest imagined shortcoming. (Worst of these: not being as angry as I was.)

Let's be clear: belief itself is the problem here. We're taught that it's the soul of decency, but it's not. Belief is meant constantly to be raked: kicked around, wrung out, scraped clean, tuned up, and thrown out entirely when broken. If you're rushing around this rock "knowing" stuff, you're morally out of control, and that makes you the problem here.

The following, in no particular order, are some of the questions I pitched myself during the gruelling Dharma combat I undertook when I became a monk. As the assiduous practice of zazen shifted me out of lawyer mode, things that had previously remained invisible – by slyly standing right on my chest – became clear.

Self-Interrogation

(Tying yourself to a chair and shining a bright light in your face is optional. But it worked for me.)

Thanks to such questions (which in Zen practice are not directly answered), I sloughed off a lot of convictions that had accrued over the years by static cling. Now I have a core of well-vetted convictions that pass muster. (Mind: I don't say that I pass muster. I still have to hurl these challenges daily, and I'm daily shamed by the results. But that shame is productive.)

So give it a shot. See what you come up with.

It's the 1 Habit of Truly Decent People: they demand more of themselves than they do of others.

(Photo courtesy of John Pavelka, Wikimedia Commons, and the Democratic People's We Totally Are Guys Just Look At The Strength Of Our Conviction Republic of Korea.)

I've encountered this misconception again and again in my half-century walkabout, first as a historian and then as a religious man. Faith is sexy. It's dramatic and macho and you get to make stirring speeches with lots of sanctimonious platitudes, like a movie hero.

But take it from me: given enough indulgence and half a chance, believers will destroy the world.

Just being embattled doesn't confer honour. Bad causes are a giant waste of time and life, to say nothing of the mountain of karmic debt. Shall we free-associate a few examples?

- the Southern cause in the American Civil War

- the Third Reich

- Soviet Communism

Yet people continue to insist they can skip the humility, self-examination, and moral courage required of competent adults, and make a thing right by sheer force of conviction.

I know what that's like. I was a revolutionary myself. I clung tightly to a list of high-minded principles. That made me angry, which I took for a mark of righteousness. And that anger made me hypocritical, untrustworthy, and ultimately counter-revolutionary. I could – and did – turn on others for the slightest imagined shortcoming. (Worst of these: not being as angry as I was.)

Let's be clear: belief itself is the problem here. We're taught that it's the soul of decency, but it's not. Belief is meant constantly to be raked: kicked around, wrung out, scraped clean, tuned up, and thrown out entirely when broken. If you're rushing around this rock "knowing" stuff, you're morally out of control, and that makes you the problem here.

The following, in no particular order, are some of the questions I pitched myself during the gruelling Dharma combat I undertook when I became a monk. As the assiduous practice of zazen shifted me out of lawyer mode, things that had previously remained invisible – by slyly standing right on my chest – became clear.

Self-Interrogation

(Tying yourself to a chair and shining a bright light in your face is optional. But it worked for me.)

- Do my convictions make me a builder, or a predator?

- Do I applaud others who call for insight and solution, or judgement and reaction?

- Am I embattled because I'm right, or because I'm wrong?

- Is my strategy "bold advance", or "dogged defence"?

- Am I fighting ideas, or people?

- When I'm conservative, what am I conserving? Is my position rational, or emotional?

- When I'm progressive, what would I impose on others? Would these measures eliminate suffering, or just redistribute it?

- Do I count a victory when my actions result in more resentment, or less? When the right people suffer, or no-one does?

- Do I abandon comrades accused of wrongdoing, or take a public stand for fairness and forgiveness?

- What about opponents?

- Do I practice realpolitik, or morality?

- Do I speak louder while attacking, or defending?

Thanks to such questions (which in Zen practice are not directly answered), I sloughed off a lot of convictions that had accrued over the years by static cling. Now I have a core of well-vetted convictions that pass muster. (Mind: I don't say that I pass muster. I still have to hurl these challenges daily, and I'm daily shamed by the results. But that shame is productive.)

So give it a shot. See what you come up with.

It's the 1 Habit of Truly Decent People: they demand more of themselves than they do of others.

(Photo courtesy of John Pavelka, Wikimedia Commons, and the Democratic People's We Totally Are Guys Just Look At The Strength Of Our Conviction Republic of Korea.)

Thursday, 31 December 2015

Forgiveness

This summary is not available. Please

click here to view the post.

Thursday, 13 August 2015

Shipwrecked

I recently re-read a journal I kept in January 2003, during the period of my divorce. I was struck by the events and emotions it recorded, and particularly the role of meditation and Zen in helping me weather them. Although the period was one of the hardest I've traversed (and there are lots of candidates), in some ways I remember it as the best. The log, which I kept to gain insight into my mood swings (and, I confess, to have someone to talk to) ends up documenting a proven strategy for surviving adversity. So for the benefit of others in similar straits, I'd like to share a few reflections.

The first pages, written when my wife was still living with me but flaunting an affair – and getting in a lot of gratuitous cruelty on the side – are especially gruelling. I was living in the great Canadian G.A.N. ("God-Awful Nowhere"), 3000 miles from my family and friends, in a culture (Québec) that wasn't mine, with no car or income. In short, I was in an abusive relationship and there was no escape. No wonder those paragraphs are so full of angst and fear.

A litany of suffering is listed there: ghastly nightmares; medical issues; niggling terror; my wife's sneering, baiting jibes; and conversely, the odd oasis of peace and reflection. Most of the latter are associated with meditation; I had been sitting twice daily for nearly a year, and snowshoeing in the forest, during which I often meditated as well. Then, suddenly, after my wife announced the date of her departure, a marked drop in stress. Pointed insight, if only in retrospect.

The role of my growing monastic practice in enduring all of this is clear in entries such as:

I've long since forgiven, in light of what I've learned, and no longer take the abuse personally. But I vividly recall what life was like with her. So it's interesting now to read the lines of grief and despair I wrote the day she left.

Still, the bedtime entry, last one in the log, sums it all up:

In my case, the Four Noble Truths, and the practice they inspired – not just reading and reflecting, but the actual doing – were that solution. It may be for you as well. Any road, you might as well try; sitting is free.

The path is always there, regardless of trailhead. May we walk it with the Buddha's own diligence and humility.

(Detail from Winslow Homer's Gulf Stream courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906] and Wikimedia Commons.)

The first pages, written when my wife was still living with me but flaunting an affair – and getting in a lot of gratuitous cruelty on the side – are especially gruelling. I was living in the great Canadian G.A.N. ("God-Awful Nowhere"), 3000 miles from my family and friends, in a culture (Québec) that wasn't mine, with no car or income. In short, I was in an abusive relationship and there was no escape. No wonder those paragraphs are so full of angst and fear.

A litany of suffering is listed there: ghastly nightmares; medical issues; niggling terror; my wife's sneering, baiting jibes; and conversely, the odd oasis of peace and reflection. Most of the latter are associated with meditation; I had been sitting twice daily for nearly a year, and snowshoeing in the forest, during which I often meditated as well. Then, suddenly, after my wife announced the date of her departure, a marked drop in stress. Pointed insight, if only in retrospect.

The role of my growing monastic practice in enduring all of this is clear in entries such as:

Good AM meditation, followed by Zen study and tea. Sunny in my cell [a tiny room in which I barricaded myself, often for whole days]. Attitude rises. Productive day. Some sadness at night, before PM meditation. The sit was OK. Cut branches outside this afternoon. Felt very good during and after. Work helps.Yet I took her actual leaving surprisingly hard. Surprising, I say, because I'd quite had enough of her by then; I was eager to live in a whole house, in peace, without a demon from some Buddhist parable whose personality had dwindled to just two channels: cold and screaming.

I've long since forgiven, in light of what I've learned, and no longer take the abuse personally. But I vividly recall what life was like with her. So it's interesting now to read the lines of grief and despair I wrote the day she left.

Still, the bedtime entry, last one in the log, sums it all up:

Things remained sad and shaky until I meditated at 10PM, for almost 50 minutes. Now I'm still sad, but less so.Because the journal ends there, it doesn't detail the accruing strength and calm of the following months, due in part to the full-on monastic discipline I adopted. Nor does it record the inevitable relapses, when depression and desperation paralysed me for an hour, or a day – or in one instance, four straight days – before I took up the practice again and forged on to healing. But the seeds of that story germinate in the telegraphic chronicle of the last month of my marriage.

Things don't happen to me,I wrote toward the end,

they just happen.And then, in response to my wife's constant insistence that I was the source of all her unhappiness:

They don't happen to her, either.Zen saved my butt, and not for the last time. I'm a monk today for the same reason my grandfather remained an FDR man till the day he died: not for theory or pretence or cachet, but from sheer fire-hardened memory. So if you're suffering, be assured that you're not alone. Others have been there – others still are – and there's an end to it.

In my case, the Four Noble Truths, and the practice they inspired – not just reading and reflecting, but the actual doing – were that solution. It may be for you as well. Any road, you might as well try; sitting is free.

The path is always there, regardless of trailhead. May we walk it with the Buddha's own diligence and humility.

- Readers interested zazen [Zen meditation] will find good instructions here.

- Zen students suffering through depression or despair will find support and companionship here.

(Detail from Winslow Homer's Gulf Stream courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906] and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thursday, 1 January 2015

New Year's Song: Et dans 150 ans

To commemorate this New Year's Day 2015 I offer a meditation on the passage of time. My brother's poetry here is so powerful I first took him for a Canadian. But on second listening I thought, no.

No. The prosody, the peculiar flow of his French; his unflinching insight, his cool under fire. This-here is a Frenchman.

Except better. Raphaël Haroche's father is a Moroccan Jew of Russian descent; his mother is Argentine. In other words, dude's a perfect storm. Prepare for bone-crystallising kensho.

Having said that, I should warn non-francophones that, as Canadian literary critic Mavis Gallant pointed out, "When poetry is translated, the result is either not faithful, not poetry, or not English." Here the author spins kaleidoscopic metaphors and convoluted word play (e.g., "bad choices" can also be "wrong guesses"; "let's drink to the street trash" becomes "let's leave them our empty coffins" when you turn it a certain way); as translator, I could only pick a shade and run with it. With luck the music and intonations will salvage some lost depth (and soften the stilted, un-English sequence of images) for non-French-speaking readers.

Finally, since the visuals in Raphaël's videos are famous for being a whole second song, I strongly recommend that you first just listen, without viewing, while reading the lyrics (below). That way your own impressions won't get wangled. Then, play the video again and just watch it, without reading. Mind blown a second time.

ET DANS 150 ANS

par Raphaël

| Et dans 150 ans, on s'en souviendra pas

De ta première ride, de nos mauvais choix, De la vie qui nous baise, de tous ces marchands d'armes, Des types qui votent les lois là-bas au gouvernement, De ce monde qui pousse, de ce monde qui crie, Du temps qui avance, de la mélancolie, La chaleur des baisers et cette pluie qui coule, Et de l'amour blessé et de tout ce qu'on nous roule, Alors souris. Dans 150 ans, on s'en souviendra pas De la vieillesse qui prend, de leurs signes de croix, De l'enfant qui se meurt, des vallées du Tiers monde, Du salaud de chasseur qui descend la colombe, De ce que t'étais belle, et des rives arrachées, Des années sans sommeil, 100 millions d'affamés Des portes qui se referment de t'avoir vue pleurer, De la course solennelle qui condamne sans ciller, Alors souris. Et dans 150 ans, on n'y pensera même plus À ce qu'on a aimé, à ce qu'on a perdu, Allez vidons nos bières pour les voleurs des rues! Finir tous dans la terre, mon dieu! Quelle déconvenue. Et regarde ces squelettes qui nous regardent de travers, Et ne fais pas la tête, ne leur fais pas la guerre, Il leur restera rien de nous, pas plus que d'eux, J'en mettrais bien ma main à couper ou au feu, Alors souris. Et dans 150 ans, mon amour, toi et moi, On sera doucement, dansant, 2 oiseaux sur la croix, Dans ce bal des classés, encore je vois large, P't'être qu'on sera repassés dans un très proche, un naufrage, Mais y a rien d'autre à dire, je veux rien te faire croire, Mon amour, mon amour, j'aurai le mal de toi, Mais y a rien d'autre à dire, je veux rien te faire croire, Mon amour, mon amour, j'aurai le mal de toi, Mais que veux-tu? |

And in 150 years we won't

remember Your first wrinkle, our bad choices How life screwed us over, and all those weapons dealers Who work for the men who pass laws for the government This pushy world, this screaming world The march of time, the melancholy The warmth of the kisses, and how the rain trickled And the love lost, and the ways they get you And so we must smile. In 150 years we won't remember How age subtracts, and hypocrisy crosses itself The dying children, the depths of the Third World The asshole hunters who blow away doves How beautiful you were, and the things ripped away The years without sleep, and 100 million hungry How doors swing shut if people see you cry The universal impulse to condemn without qualm And so we must smile. And in 150 years, we won't even recall The things we loved, and those we lost Come on, let's drink to the street trash! My God, we'll all end up in the ground! Such a disappointment! Just look how those skeletons sneer at us But don't glare back; don't make war on them They'll keep nothing of us -- or themselves -- in the end As well cut off my hands, or burn them And so we must smile. And in 150 years, my love, you and I Will be – softly, dancing – two birds carved on a tombstone In this high school prom for dropouts, I'm looking beyond Maybe we'll come back some day; shipwrecked, perhaps But there's nothing for it, and I don't want to lie My love, my love, I'll miss you so But there's nothing for it, and I don't want to lie My love, my love, I'll miss you so But what can we do? |

He's right, brothers and sisters. In 150 years, no-one will remember a thing we've done or said, or that we ever lived; for the vast majority of us, our very names will never be pronounced again.

You can take it for cruelty or compassion, but you can't change it. Our human being survives time like a beetle survives a millstone. And in the same form.

May we all cultivate, in the coming year, that which endures.

Topics:

acceptance,

compassion,

death,

dependent co-arising,

forgiveness,

France,

gratitude,

hermit practice,

impermanence,

langue française,

mindfulness,

music,

New Year's,

poem,

Raphaël,

video

Thursday, 16 October 2014

Everyone

Everyone has a room to air.

Everyone has a soul to bare.

Everyone has a horn to blare.

Everyone has a cause to care.

Everyone has a task to chair.

Everyone has a doubt to dare.

Everyone has a bent to err.

Everyone has a hull to fair.

Everyone has a flame to flare.

Everyone has a growl to glare.

Everyone has a hound to hare.

Everyone has a glove to pair.

Everyone has a call to prayer.

Everyone has a chance too rare.

Everyone has a crow to scare.

Everyone has a song to share.

Everyone has a snipe to snare.

Everyone has a coin to spare.

Everyone has a debt to square.

Everyone has a scowl to stare.

Everyone has an oath to swear.

Everyone has a page to tear.

Everyone has a road to there.

Everyone has a robe to wear.

Everyone has a soul to bare.

Everyone has a horn to blare.

Everyone has a cause to care.

Everyone has a task to chair.

Everyone has a doubt to dare.

Everyone has a bent to err.

Everyone has a hull to fair.

Everyone has a flame to flare.

Everyone has a growl to glare.

Everyone has a hound to hare.

Everyone has a glove to pair.

Everyone has a call to prayer.

Everyone has a chance too rare.

Everyone has a crow to scare.

Everyone has a song to share.

Everyone has a snipe to snare.

Everyone has a coin to spare.

Everyone has a debt to square.

Everyone has a scowl to stare.

Everyone has an oath to swear.

Everyone has a page to tear.

Everyone has a road to there.

Everyone has a robe to wear.

(Photo of Fuke Zen monk courtesy of Urashima Taro and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

acceptance,

alienation,

blessing,

compassion,

depression,

dukkha,

forgiveness,

gratitude,

hermit practice,

meditation,

mindfulness,

poem,

Zen

Thursday, 25 September 2014

Good Book: At Hell's Gate: A Soldier's Journey from War to Peace

I'm not sure he'd appreciate the label, but Claude AnShin Thomas is the most prominent hermit of our generation. Though an ordained priest in Bernie Glassman's Zen Peacemaker lineage, his practice is in the tradition of Bashō. In his own words:

Where, you wonder, does a guy get gravel like that? Well…

In At Hell's Gate: A Soldier's Journey from War to Peace, AnShin describes his military service in Vietnam, where he clocked 625 combat hours in US Army helicopters, many behind an M60 machine gun. By his own recollection, he was in combat virtually every day from September 1966 to November 1967. He was, in short, the classic "badass American fighting man" so beloved of Hollywood.

Except it wasn't as fun.

He came home, like all war veterans, to a society desperate never to hear about those not-fun parts, or to pay for the care he now required for life. The tale that ensues has been told a hundred times, and each time is the first.

Re-reading At Hell's Gate (one of my all-time favourite Zen books) I was struck again by the sense that the author would rather not be writing it at all. There's a reticence in AnShin's prose, a tone of compelled confession, that suggests modesty, circumspection, and discomfort with the writer's art, at which he clearly doesn't feel proficient. Which is exactly why he is. You're not reading a writer; you're reading a veteran, in much more than just the military sense.

Interspersed among terse, almost telegraphic accounts of his past is some of the best how-to on practical meditation I've found. His themes are universally relevant: depression and despair; atonement and redemption; suffering and transcendence. All from a guy who speaks with thunderous authority.

His eremitical bona fides are equally evident. He writes:

My lone criticism of At Hell's Gate is its light treatment of those incredible pilgrimages. In fact, I wish AnShin would write a whole 'nother book just about them. I appreciate his desire to avoid the odour of self-glorification; first-person journalism is a hard beat for a non-narcissist. And as a mendicant, he likely doesn't have time or space to sit down and write. But it's badly needed. I hope AnShin's sangha convince him someday to transmit and preserve these vital experiences, for the benefit of future generations. After all, where would we be if Bashō had remained silent?

Nevertheless, the book we already have is all by itself a repository of rare and hard-earned wisdom, a chronicle of unusual violence and damage, leading to unusual insight. The man himself puts it best:

"I made the decision to take the vows of a mendicant monk primarily because I wanted to live more directly as the Buddha had. […] Also, in witnessing the evolution of Zen Buddhist orders in the United States, I wanted to evoke the more ancient traditions of those who embarked on this spiritual path and to live my commitment more visibly."AnShin specialises in walking ango – long voyages on foot, without money, living off the Dharma and the compassion of others. He calls them peace pilgrimages, and to date he's walked from Auschwitz to Vietnam; across the US and Europe; in Latin America; and even the Middle East. He also leads street retreats, a unique Peacemaker practice wherein Zen students take the Buddha at his word and become Homeless Brothers in the urban core of a large city for a specified period of time.

Where, you wonder, does a guy get gravel like that? Well…

In At Hell's Gate: A Soldier's Journey from War to Peace, AnShin describes his military service in Vietnam, where he clocked 625 combat hours in US Army helicopters, many behind an M60 machine gun. By his own recollection, he was in combat virtually every day from September 1966 to November 1967. He was, in short, the classic "badass American fighting man" so beloved of Hollywood.

Except it wasn't as fun.

He came home, like all war veterans, to a society desperate never to hear about those not-fun parts, or to pay for the care he now required for life. The tale that ensues has been told a hundred times, and each time is the first.

Re-reading At Hell's Gate (one of my all-time favourite Zen books) I was struck again by the sense that the author would rather not be writing it at all. There's a reticence in AnShin's prose, a tone of compelled confession, that suggests modesty, circumspection, and discomfort with the writer's art, at which he clearly doesn't feel proficient. Which is exactly why he is. You're not reading a writer; you're reading a veteran, in much more than just the military sense.

Interspersed among terse, almost telegraphic accounts of his past is some of the best how-to on practical meditation I've found. His themes are universally relevant: depression and despair; atonement and redemption; suffering and transcendence. All from a guy who speaks with thunderous authority.

His eremitical bona fides are equally evident. He writes:

"Anyone can come with me on a pilgrimage. It's not necessary for a person to become a student of mine or to spend time with me to learn this practice. It is open."In these angos – which he defines as "just walking" – he's revived a practice largely abandoned in the era of institutional Zen:

"There is no escape from the nature of your suffering in this practice. When you walk, you are constantly confronted with your self, your attachments, your resistance. You are confronted with what you cling to for the illusion of security."Should anyone require more evidence of AnShin's hermitude, his Further Reading section includes Zen at War, The Cloud of Unknowing (a classic of Christian contemplation), and the Gnostic Gospels, though none of them are cited in the text.

My lone criticism of At Hell's Gate is its light treatment of those incredible pilgrimages. In fact, I wish AnShin would write a whole 'nother book just about them. I appreciate his desire to avoid the odour of self-glorification; first-person journalism is a hard beat for a non-narcissist. And as a mendicant, he likely doesn't have time or space to sit down and write. But it's badly needed. I hope AnShin's sangha convince him someday to transmit and preserve these vital experiences, for the benefit of future generations. After all, where would we be if Bashō had remained silent?

Nevertheless, the book we already have is all by itself a repository of rare and hard-earned wisdom, a chronicle of unusual violence and damage, leading to unusual insight. The man himself puts it best:

"Everyone has their Vietnam. Everyone has their war. May we embark together on a pilgrimage of ending these wars and truly live in peace."If you're suffering – whether firearms were involved or just plain-old heartbreak – read this book.

Topics:

ango,

At Hell's Gate,

aviation,

Bashō,

Bernie Glassman,

book,

Claude AnShin Thomas,

depression,

forgiveness,

hermit practice,

meditation,

redemption,

review,

Vietnam,

Zen at War

Thursday, 21 August 2014

Robin Williams and Atonement

I've purposely held off posting about Robin Williams until the tidal wave of pro forma anguish washed past and left us in a place of calm. I'll give the media this: this time the coverage wasn't schlocky and over-the-top. Which is good, because the man deserves better.

But given the way he went, and the fact that August has somehow become Suicide Month here at Rusty Ring, I've got stuff to say.

First off, Robin Williams was a crucial figure to my generation. I haven't seen this mentioned anywhere – not surprising, given that those of us who followed the Baby Boomers have always been studiously ignored. But Robin Williams was, to some extent, our John Lennon. The fact that he was apolitical suited us perfectly; so were we. His lightning genius was dazzling, his sword scalpel-sharp, though he never seemed to over-use it. He took down the officious and precious, but never harped or dwelled. In nearly every photograph a childlike gentleness glows in his eyes. He wasn't angry; he was self-mocking. In him we saw perhaps not ourselves, but what we wished we could be. And on a personal note, as a kid of Scottish descent growing up in the States, I'll be eternally grateful to him for finally convincing the Yanks that Robin IS TOO a boys' name. (Haven't been hassled about that since Mork.)

None of which I realised until he was gone. Sic transit gloria mindfulness practice.

With his passing, my man Robin also brought depression to international attention, resulting in myriad thoughtful, helpful articles about the relationship between creativity, damage, and loneliness. Last week my 2011 review of The Zen Path Through Depression trended worldwide, attracting hundreds of hits. So people are interested in the topic, and with luck some who need counsel are seeking it.

But one thing I haven't seen is any discussion of the collective responsibility for the condition and its consequences. Some time ago I read a study in which researchers assembled a group of depression patients and another of random others. Researchers gave each individual a series of open-ended true stories and asked them to predict the outcome. The depressed subjects consistently augured more accurately than those in the control group.

Get it? Another word for depression is insight. Often, depressed people suffer in part from the misfortune of not being as mentally incapacitated by denial as their cohorts. The implication is clear: at least some of depression isn't sickness at all; it's a tragic lack of sickness, in a world gone barking mad.