If you haven't discovered Avi Steinberg, you're in for a treat. (And if you have, a welcome visit back.)

Avi's deceptively simple New Yorker cartoons have a knack for penetrating the heart of the problem, often in ways that illuminate the crux of our delusions. Though not a Zenner to my knowledge, his work repeatedly strikes Zen-adjacent targets with a clarity worthy of Nasrudin.

I've avoided possible insult to Avi's copyright by not posting any examples on this page, though the writer in me is, like, "Really? You're trying to drive traffic to his Substack without showing anybody why they should go?"

But such is the looking glass of these greedy times.

So you'll have to trust me. Click the links. See what I'm talking about.

Start here.

I don't know if the guy meditates, but this about sums it up. It's part of a protracted exploration of the nature of anxiety, of which pretty much every frame is gold.

Then sample a few from his timeline:

Winning.

The perils of mindfulness.

Why it's hard to keep writing.

Then click through to some more.

Or just Google Avi and click on Images.

And then we'll all sue him for stealing our lives.

(Photo of Hotei figurine courtesy of Adrian Pingstone and Wikimedia Commons.)

'Way back in 1973, Paul Simon released a song called One Man's Ceiling Is Another Man's Floor. The lyrics are classic Paul: a Dylanesque flow of images that makes sense on an intuitive level.

But as a many-time flat dweller, it's the title refrain that means most to me. For like the best of Sufic teachings, its significance changes as you turn it in the light.

At base, it seems to mean "walk mindfully, because your tromping will be amplified in other rooms."

Or it could be a social justice message about the people you – wittingly or un- – exploit for your own comfort and well-being.

Conversely, it may be telling us that those limits we allow to confine us, a more visionary person could use to launch him- or herself to the stars.

Or maybe it just refers to the fact that we all live within a vast complex of shared boundaries, where freedom, if it exists, is more a matter of accord than licence.

Whatever the case (bit of a deep-dive Zen pun, there), I like to sit with Paul's one-sentence koan from time to time; see where it lands in that moment.

(Photo courtesy of Rawpixel.com and a generous photographer.)

If you'd like to explore a rich source of provocative, not overly-technical Zen reads, check out Sotozen.com. Among its many offerings is an attractive compendium of Zen stories, presented with penetrating opening commentary. A good start might be this favourite example, starring the decidedly un-Soto Ikkyu.

If you'd like to explore a rich source of provocative, not overly-technical Zen reads, check out Sotozen.com. Among its many offerings is an attractive compendium of Zen stories, presented with penetrating opening commentary. A good start might be this favourite example, starring the decidedly un-Soto Ikkyu.

As you'll see, the infamous Rinzai master strongly recalls Nasrudin – an old friend who figures on this blog – and also Alan Watts.

In any case, the Ikkyu story provides another meditative exposition of conventional authority: sometimes they kick you out and sometimes they lock you in, but in all cases you must be where they tell you to be.

And while you're up, enjoy a good surf around Sotozen.com. It's a valuable resource for our lot.

(Shiba Zojoji, by Kobayashi Mango, courtesy of Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thus I am one of few goyim to have experienced the blessing of Jewish grandparents.

During that time I came to relish the Hebrew world view – so similar to my own Scottish and Old Settler heritage, yet so... not.

Upgraded, as it were. Different data, same conclusion. And with a wicked snap no Scot could despise.

So twenty years later, when, having become a Zen monk, I encountered the following online, I was primed to appreciate it.

The following is one of many well-shared excerpts from Zen Judaism: For You a Little Enlightenment, a short 2002 book by David M. Bader that took the early Net by storm. The site I saved my own text from has long since gone to the 404 meadows, but Heller Web Space preserves a close facsimile, with appropriately Web 2.0 æsthetics.

So enjoy this spin on the wisdom of the Ancestors, with refreshingly Nasrudinic clarity.

Zen Judaism

by David M. Bader

1. If there is no self, whose arthritis is this?

2. Be here now. Be someplace else later. Is that so complicated?

3. Drink tea and nourish life. With the first sip... joy. With the second... satisfaction. With the third, peace. With the fourth, a danish.

4. Wherever you go, there you are. Your luggage is another story.

5. Accept misfortune as a blessing. Do not wish for perfect health or a life without problems. What would you talk about?

6. The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single "oy".

7. There is no escaping karma. In a previous life, you never called, you never wrote, you never visited.And whose fault was that?

8. Zen is not easy. It takes effort to attain nothingness. And then what do you have? Bupkes.

9. The Tao does not speak. The Tao does not blame. The Tao does not take sides. The Tao has no expectations. The Tao demands nothing of others. The Tao is not Jewish.

10. Breathe in. Breathe out. Breathe in. Breathe out. Forget this, and attaining Enlightenment will be the least of your problems.

11. Let your mind be as a floating cloud. Let your stillness be as the wooded glen. And sit up straight. You'll never meet the Buddha with such rounded shoulders.

12. Be patient and achieve all things. Be impatient and achieve all things faster.

13. Deep inside you are ten thousand flowers. Each flower blossoms ten thousand times. Each blossom has ten thousand petals. You might want to see a specialist.

14. To practice Zen and the art of Jewish motorcycle maintenance, do the following: Get rid of the motorcycle. What were you thinking?

15. Be aware of your body. Be aware of your perceptions. Keep in mind that not every physical sensation is a symptom of a terminal illness.

16. The Torah says, "Love thy neighbour as thyself." The Buddha says there is no "self." So, maybe you are off the hook.

17. The Buddha taught that one should practice loving kindness to all sentient beings. Still, would it kill you to find a nice sentient being who happens to be Jewish?

18. Though only your skin, sinews, and bones remain, though your blood and flesh dry up and wither away, yet shall you meditate and not stir until you have attained full Enlightenment. But first, a little nosh.

(Photo courtesy of Unsplash.com and a generous photographer.)

One day Nasrudin was walking down a country road when he saw a group of horsemen riding toward him at great speed. Fearing bandits, he quickly jumped over a nearby wall and found himself in a graveyard.

"Where to hide?" he cried. Looking desperately about, he spied an open grave.

Meanwhile, having seen his troubled behaviour, the riders dismounted and followed Nasrudin into the cemetery. At length they found him trembling with fear at the bottom of the hole.

"Ho, fellow traveller!" they called down. "We were riding this way and saw you flee something. Do you need any help? Why are you in this grave?"

"Well," said Nasrudin, "as to that, simple questions often have complex answers.

"About all I can tell you is, I am here because you are, and you are here because I am."

(Photo of Adolph Schreyer painting courtesy of Sotheby's and Wikimedia Commons.)

A Western Zenner was visiting sacred sites in the mountains of Korea, when he happened upon the hermit Hyung meditating beside a stream.

A Western Zenner was visiting sacred sites in the mountains of Korea, when he happened upon the hermit Hyung meditating beside a stream.

"Why, you must be the great Hyung-roshi!" said the hiker. "Is it true that you live in perfect harmony with nature, never wanting for anything?"

"Yes," said Hyung, equanimously ignoring the Japanese honorific. "The living things of this mountain are my sangha, and they support my practice without fail."

"Give me a story to take home!" the tourist begged.

"Well," said Hyung, "a fish once saved my life."

"Wonderful!" cried the visitor. "How did this miracle happen?"

"I ate him," said Hyung.

Wu Ya's commentary: "Heroic fish gives his life for the flowers."

(A similar tale can be found in the teachings of Nasrudin.)

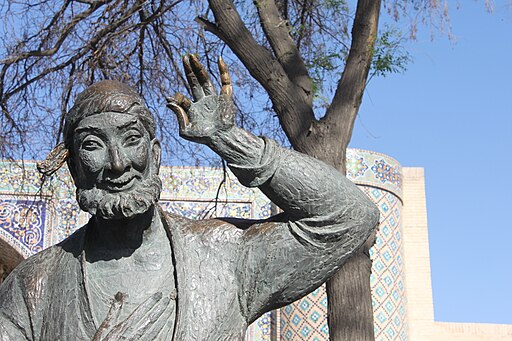

Zen is famous for its koans, those quirky, inscrutable Chinese stories that make no sense but are somehow profoundly true. My own devotion to it is rooted in this classic literature: the thunderous wisdom encoded in The Blue Cliff Record, The Book of Equanimity, and The Gateless Gate.

Zen is famous for its koans, those quirky, inscrutable Chinese stories that make no sense but are somehow profoundly true. My own devotion to it is rooted in this classic literature: the thunderous wisdom encoded in The Blue Cliff Record, The Book of Equanimity, and The Gateless Gate.

But the Sufis (Zen Muslims, more or less) may have us beat; not only do they have a prolific koanic tradition of their own, theirs are funny. All while sacrificing none of the point.

These teaching stories, collectively known as The Tales of Nasrudin (نصر الدين خواج , خواجه نصرالدین , نصرالدین جحا ; Nasrudeen, Nasreddin, Nasruddin, Nasr ud-Din, Nasredin…), chronicle the continuing misadventures of an Islamic scholar of that name. Like all academics (to say nothing of religious leaders), Mullah Nasrudin can be long on theory and short on practice, but his gift for brilliant, backhanded insight always makes for a worthwhile visit.

Back in November 2012 I ran one of my favourite examples in Rusty Ring's Kyôsaku series of observations by noted teachers. Others include:

- The host of an elegant feast required all guests to wear fine clothes. When Nasrudin arrived, he began stuffing food into his shirt and trousers. The host confronted him angrily:

"What do you mean by this?"

"Since clothes are more important than people," Nasrudin answered, "they should eat first."

- Two children arguing over a bag of marbles came to the mullah to settle the matter. "Would you like Man's justice or Allah's?" asked Nasrudin.

"Why, Allah's, of course," replied the children.

"Very well," said Nasrudin, and gave three marbles to one and nine to the other.

- "Mullah," asked a townsman, "is your theology orthodox?"

"That depends," said Nasrudin. "Which heretics are in charge at the moment?"

- "Nasrudin," said another, "four years ago you told me you were forty. Today you still say you're forty. How do you explain this?"

"I am an honest man!" said Nasrudin. "Whenever you ask me a question, you shall always get the same answer."

- One day Nasrudin was walking along a river when a man cried out to him from the far bank:

"How can I get across?"

"You are across!" shouted the mullah.

(Note that there's a classic koan virtually identical to this, but not the least bit funny. The Sufis took the same wisdom, employed exactly the same imagery, and added a rimshot.)

In Sufi tradition, contemplators are frequently invited to offer commentary of their own, in the form of a suggested moral. In some fora, the list of these responses can be longer than the actual story, each one subtly spinning the punch-line into new – even conflicting – teachings. (Indeed, scholars as august as Idries Shah have even mined the humour of other cultures for that nugget of sanity that all comedy contains.) What a refreshing challenge to our own tradition, where only recognised scholars are permitted to comment.

My man Nasrudin has left his tracks all over the Internet – a medium made for him if ever there was one – and that's good news for his fans. Fertile starting points include The Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin, NewBuddhist.com, WrongPlanet.net, Godlike Productions, and WikiQuote. Load 'em up and laugh.

All the wisdom, half the pomposity.

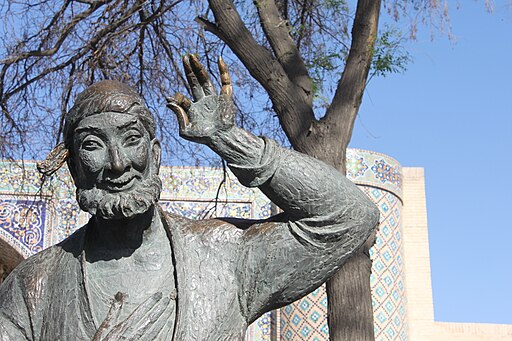

(Photo of the Nasrudin statue in the Lab-i Hauz Complex, Bukhara, Uzbekistan, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

While on a trip to another village, Nasrudin lost his favourite copy of the Qur'an.

Several weeks later, a goat walked up to Nasrudin, carrying the Qur'an in its mouth.

Nasrudin couldn't believe his eyes. He took the precious book out of the goat's mouth, raised his eyes heavenward and exclaimed, "It's a miracle!"

"Not really," said the goat. "Your name is written inside the cover."

From the Tales of Nasrudin.

(Photo courtesy of George Chernilevsky and Wikimedia Commons.)