The Way is a movie you've seen a dozen times: angry/critical/selfish/

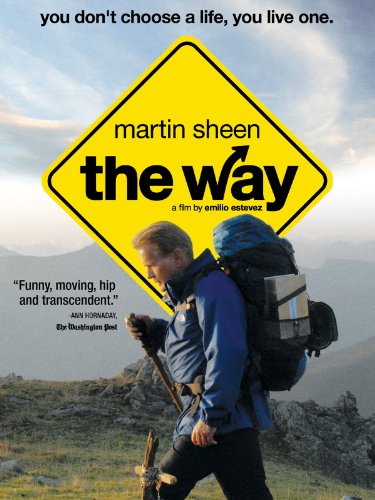

The Way is a movie you've seen a dozen times: angry/critical/selfish/disapproving/distant father comes to regret his bullheaded incompetence at the whole human thing. It's also a movie you've never seen before, and I recommend that anyone who has a dad, or is a dad – or is a man, or knows a man – remedy that.

The plot, as I said, is well-travelled, but what saves the film from that (and sometimes itself) is its lead actor's astounding fluency in silence. If nothing else, The Way proves that if you want to make a movie about a man struck speechless by suffering, you're gonna need Martin Sheen. Guy's like the Robin Williams of stillness.

For reasons I can't reveal without spoiling, Tom Avery decides, without a lick of reflection or experience, to hike the Camino de Santiago. This ancient Christian pilgrimage route, winding through the daunting Pyrenees from one side of the Iberian Peninsula to the other, has lately become très chic among aging Boomers. But very few of them actually do it; as a range cop at the trailhead advises our hero, that takes two to three months. If you're in shape. And you have the fire.

Which Avery may; I'll leave that for viewers to discover. But in his desperate search for solitude, our man ends up, Jeremiah Johnson-style, a reluctant surrogate

father to a gaggle of young, equally wounded fellow pilgrims. The fact that he has the same prickly dynamic with them that he has with his actual son, is a bit heartbreaking. Yet, pointedly, it works. The filmmaker seems to be telling us, in hauntingly familiar tones, that eighty per cent of fatherhood is just showing up.

father to a gaggle of young, equally wounded fellow pilgrims. The fact that he has the same prickly dynamic with them that he has with his actual son, is a bit heartbreaking. Yet, pointedly, it works. The filmmaker seems to be telling us, in hauntingly familiar tones, that eighty per cent of fatherhood is just showing up.Which is particularly bittersweet, given that filmmaker Emilio Estevez, who also wrote and directed the screenplay and played Avery's son, is in fact Martin Sheen's real-life son. All told, the project involved three generations of Estevez men – father, son, and grandson – before and behind the camera.

I was bemused, while researching this review, to find most commentary about The Way on Christian sites. Thus do we chop complex realities into simplistic tropes. Yeah, hiking the Camino is a Roman Catholic thing. And yeah, Tom Avery is Catholic (as are the Estevez family). His faith is apparently one of the tools he takes into the mountains. I say "apparently" because he never utters a Christian word. Neither, come to that, does anyone else; even a priest they meet is refreshingly circumspect. Nobody totes a Bible; nobody prays, at least not formally; nobody mentions Jesus. If it weren't for Avery's briefly crossing himself during a specific repeated ritual, you'd have no idea he was a believer. In anything.

Yet mainstream outlets seem terrified of the sectarian implications of a pilgrimage, while the Christian market glommed hard onto a film with a big-name star. (The fact that many sources were Evangelical underscores the general confusion over "whose" movie this is. Estevez has verified that this was a conscious strategy on his part.) Basically, The Way is several films; sooner or later, it ends up being about everybody.

Yet mainstream outlets seem terrified of the sectarian implications of a pilgrimage, while the Christian market glommed hard onto a film with a big-name star. (The fact that many sources were Evangelical underscores the general confusion over "whose" movie this is. Estevez has verified that this was a conscious strategy on his part.) Basically, The Way is several films; sooner or later, it ends up being about everybody.But one way or the other (get it?), this is a very Buddhist film. C'mon, brothers and sisters: this whole "way-path-journey" thing is our metaphor, eh? And the Estevez spin it particularly well. I defy any Zenner, having seen The Way, to tell me it's a "Christian" movie. (And I defy any Christian to tell me it's not.)

Of course, the viewer-pilgrim is bound to get a few pebbles in his or her sandal along the road. There's a digression involving the Rom that reads like an episode from an old American TV series. The actors' raw commitment carries that off, but harder to dismiss is a subplot that plays smoking as poetic, inconsequential, even cute. It is none of those things. Hollywood is largely responsible for the perpetuation of this devastating – and goddam rude – addiction, and I earnestly wish it would grow the hell up and get over its teeny-bopper fascination with tobacco.

But the film survives this lapse, even if the character will not. Its decidedly fly- (or walk-) by-night production model delivers scene after magnetically attractive, entirely authentic scene, drenched in immediacy. Estevez has a rare gift for spotting eloquent shots, and here he's inadvertently made one of the best tourist board adverts ever. Watching it, I'm thinking, "What this trail needs is a Zen hermit monk."

Best of all is the ending, which – and here I don't think I'm giving anything away – is realistically open-ended. This reviewer gets a little weary of cinematic "happily ever after" (and its evil twin, "broken forever") outcomes. Life goes on. It's easier to relate to, and to care about, lives that continue after the credits roll.

Why we keep making this movie over and over would be an excellent topic for a doctoral thesis. Why we keep watching it is grist for meditation. I highly doubt The Way will be the last damaged-dad picture ever made. I am equally sure that while some of its successors may be as good, none will be better.