Showing posts with label dukkha. Show all posts

Showing posts with label dukkha. Show all posts

Thursday, 26 June 2025

Dukkha Koan

Topics:

dukkha,

Fudo Myō-ō,

hermit practice,

koan,

The Rusty Ring Art Gallery

Thursday, 11 November 2021

Thursday, 29 October 2020

The Deal

Regulars may have noticed that posting on Rusty Ring has become a little haphazard. That's because I've been managing my mother's home hospice for the last two months. Aside from the daily march of tasks, it also includes regular upheavals in routine, resulting in topsy-turvy days and weeks. Since predictable scheduling is the first requirement of blogging, the results are showing up here.

The underlying situation is of course a source of stress, making the actual work a kind of distraction – and therefore a relief – in an ironic way. But once again I'm finding meditation invaluable. As ever, I hesitate to vaunt it too much, as newcomers and interested non-meditators may form inaccurate expectations.

Zazen doesn't fix anything. It doesn't make me care less, and I'm not sure it even makes me fear less.

It just makes me fear better.

If that makes no sense, welcome to Zen.

I have no idea how I survived these things before I became a monk.

Anyway, I'll continue striving to maintain the regular posting schedule, in full knowledge that I'm bound to fail. And I'll concentrate on offering stuff of value when I do, even if it's a line here and a quotation there.

Because one of the sub-vows of my Rule is, "I will do what I can, even if it's unlikely to succeed."

Peace and progress to all seekers.

(Graphic courtesy of Zoltan Tasi and Unsplash.com.)

Thursday, 17 September 2020

Thursday, 16 July 2020

Street Level Zen: Dukkha

Topics:

dukkha,

Gilda Radner,

hermit practice,

Street Level Zen,

the 70s,

Zen

Thursday, 14 May 2020

Street Level Zen: Strength

Topics:

bodhisattva,

depression,

dukkha,

Ernest Hemingway,

hermit practice,

redemption,

Street Level Zen,

suicide

Thursday, 20 February 2020

Preference Meditation

Topics:

dukkha,

hermit practice,

meditation,

non-attachment,

Thailand

Thursday, 3 August 2017

Everything Doesn't Happen For A Reason

A few weeks ago a friend directed me to Everything Doesn't Happen For A Reason, by Tim Lawrence. It's attracted an enthusiastic following online, and since August has become the traditional time for Rusty Ring to address such topics, I figure this is my opening.

A few weeks ago a friend directed me to Everything Doesn't Happen For A Reason, by Tim Lawrence. It's attracted an enthusiastic following online, and since August has become the traditional time for Rusty Ring to address such topics, I figure this is my opening.Tim's central hypothesis – you gotta love writers who state their thesis right in the title – is also a primary Zen principal, but his objective trends rather more to the negative than affirmative.

Specifically, he's that tired of grieving people being told they're "suffering for a reason", that it's all part of some great compassionate plan, that "God never gives you more than you can handle."

"That's the kind of bullshit that destroys lives," he says. "And it is categorically untrue."

Preach, brother. The problem with the "everything happens for a reason" crowd, aside from their faulty analysis, is that they lay a giant trip on the injured, just when their resistance is low. Now they're dumb, weak – hell, even ungrateful – as well.

Tim goes on to finger the origin of this nonsense:

...our culture has treated grief as a problem to be solved, an illness to be healed, or both. In the process, we've done everything we can to avoid, ignore, or transform grief. As a result, when you're faced with tragedy you usually find that […] you're surrounded by platitudes.

…In so doing, we deny [sufferers] the right to be human. [My emphasis.]It's a hallmark of some worldviews to meet dukkha with weapons-grade denial. If you insist the Universe is ruled by a benevolent force, or that a given socio-political system is self-correcting, you'll immediately bang your skull on the titanium grille of the ever-oncoming First Noble Truth. Then you'll have to abandon all positive ends and exhaust your remaining intellectual capital on explaining why bad things keep happening in your Dictatorship of Infinite Good.

Therefore, for the benefit of all sentient beings, Ima say it right out loud:

Life is pain.

This is a direct result of the inescapable nature of existence. (Seriously. Don't try to escape it. That's a major source of pain. Second Noble Truth, for those of you playing at home.)

All of that is orthodox Buddhism – though Tim is an Anglican monastic. There is, however, one aspect of his programme that flirts with unskilfulness.

He's big into "letting people go".

Not that this isn't often an excellent idea. Good people tend to allow themselves to be abused, on the belief, inbred or inculcated, that they somehow deserve it, or that they owe it to others. Like other decent folks, I've suffered at the hands of those who took advantage of my patience and good will. I should have let those people go right off. Ideally before I picked them up.

However, like all weapons, this one is apt to wound its wielder, especially if overused. Thus Tim:

If anyone tells you that all is not lost, that it happened for a reason, that you’ll become better as a result of your grief, you can let them go.Seems a tad trigger-happy to me. I've often said useless things, maybe even hurtful ones, to people I authentically wanted to support. Problem was I didn't know what to say.

(Free tip from our Hard-Earned Insight Department: Sometimes you can't help. Sadly, the world is still awaiting the self-improvement book How to Help When You Can't Help.)

So let's not lose our humanity, here. When I've been in the worst possible shape, my capacity to remain human in the face of inhumanity has been tremendously gratifying.

Tim also loses me when he suggests that grief won't make you a better person. It damn well will, if you're determined that it will. As self-centred as I am now, I'm a buddha compared to what I was before. If recent politics prove anything, it's our moral obligation to suffer intelligently.

But of course it's not skilful to say that to someone in the throes of heartache. Instead, I try to offer tested survival tips from my own laboratory. And, since guilt and regret are key components of grief, I also bear witness to their decency. Psychopaths don't suffer.

Still, advising others is fraught. Often the best tack is just to accompany the sufferer in shared silence, accepting the person and the pain. Especially, to remember him or her actively. Call and text (that strange word again: "and"), visit, invite him or her out, break the isolation that's the warhead of both shame and grief.

Tim makes all these points, and others as well, in his timely essay. There's a reason it's been so well-received. Whether you're in pain yourself, or accompanying someone who is, give it a read.

(Photo of artist drawing Kanzeon, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, courtesy of Republic of Korea Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

Avalokiteshvara,

bodhisattva,

Buddhism,

depression,

dukkha,

Four Noble Truths,

Tim Lawrence,

Zen

Thursday, 8 June 2017

Economics

(The following is a passage from Rough Around the Edges, a manuscript I began 20 years ago. Though my Zen practice was still about six years in the future, it's interesting to me today to read a fundamentally exact description of what the Buddha called "world weariness" – the mainspring of enlightenment practice – written in my own pre-monastic hand. Like the man said, we come by it honestly.)

The problem, the problem. What is the problem?

You're born. Somewhere, someone sets an egg timer. For a quarter-hour you rave like a rich man in a burning mansion, snatching at a vase, a string of pearls, anything to show you lived there.

The timer dings; you're unborn. The necklace falls to the ground.

We get it about wealth. The prophets have all warned us. But there are other treasures just as fleeting.

I hunger for love, to share life, and not to be alone. Except it won't do. Even if you find love, the timer still goes ding. The necklace falls to the ground.

What's the problem? I'm afraid to die alone. But I live alone. I work alone, and most of the time, I love alone.

The seconds tick. The words echo in my mind. A thought occurs:

Perhaps the most valuable thing in that house is the fire.

(Adapted from Rough Around the Edges: A Journey Around Washington's Borderlands, copyright RK Henderson. Photo of the mechanics of egg-timing courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and generous photographer.)

The problem, the problem. What is the problem?

You're born. Somewhere, someone sets an egg timer. For a quarter-hour you rave like a rich man in a burning mansion, snatching at a vase, a string of pearls, anything to show you lived there.

The timer dings; you're unborn. The necklace falls to the ground.

We get it about wealth. The prophets have all warned us. But there are other treasures just as fleeting.

I hunger for love, to share life, and not to be alone. Except it won't do. Even if you find love, the timer still goes ding. The necklace falls to the ground.

What's the problem? I'm afraid to die alone. But I live alone. I work alone, and most of the time, I love alone.

The seconds tick. The words echo in my mind. A thought occurs:

Perhaps the most valuable thing in that house is the fire.

(Adapted from Rough Around the Edges: A Journey Around Washington's Borderlands, copyright RK Henderson. Photo of the mechanics of egg-timing courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and generous photographer.)

Topics:

Buddha,

dukkha,

enlightenment,

Four Noble Truths,

hermit practice,

impermanence,

Rough Around the Edges,

samsara,

Zen

Thursday, 3 November 2016

Penance

Some time ago I had the good fortune to spend a month in Guatemala. While in the ancient capital I visited the tomb of Hermano Pedro, a Franciscan saint who looms large in the faith and history of that country.

Preserved there is Pedro's old cell, wherein visitors can meditate on the meagre possessions of a man who gave his life to advocating for and serving the poor. It boils down to one change of clothing; a chair and a walking stick; a bed sheet and sundry devotional items; and a human skull, used by Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu monastics in times past to keep their head in the game, so to speak.

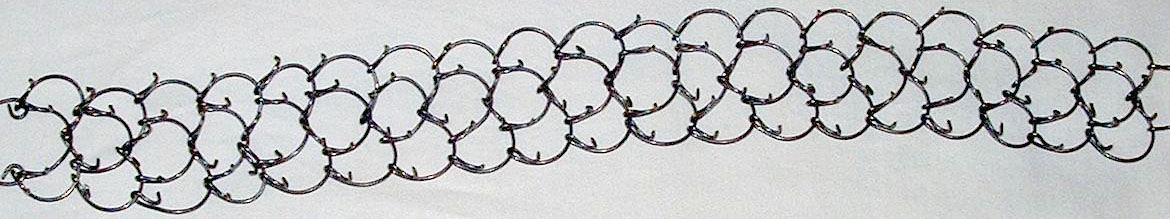

But what really caught my attention was his cilice collection: instruments he used to scratch, flog, and rip his flesh. There was a hair shirt, a rope knout with big, mean knots, and a steel contraption that looked remarkably like a small chain harrow. This last turned out to be worn beneath the shirt, to much the effect you'd imagine.

Later, describing this visit to a close Franciscan friend, I teased him about the equipment I'd seen. Why, I asked, had he never shown me the torture devices he'd been issued on his own ordination?

"Since my brother's day," Pierre answered, "our Order has learned that chasing pain is a waste of time.

"If you just sit quietly and wait, suffering will find you."

(Photos courtesy of Opus Dei Awareness Network [contemporary cilice], Hermann Luyken [Hermano Pedro's tomb and chapel in Antigua, Guatemala], and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

Buddhism,

Christianity,

dukkha,

forgiveness,

Franciscan,

Hermano Pedro,

hermit practice,

monk,

torture

Thursday, 19 May 2016

Good Movie: My Life as a Dog

"It could have been worse."

"It could have been worse."So says the young protagonist of Mitt liv som hund ("My Life as a Dog"). For him, every misfortune is an opening to Kuan Yin.

That the speaker is twelve; that his life is crap; and that there's no reason to suspect it's going to get any better, tells you this is no ordinary kid.

My Life as a Dog was made in the Eighties, when my parents' generation came into their "power years" – the moment just before retirement when a peer group finds itself running things. Movie-wise, the result was a slew of barely-fictionalised memoirs of childhoods spent negotiating World War II and its aftermath.

A festival of these films – all of them superb – might include Le Grand Chemin, Empire of the Sun, Hope and Glory, Au Revoir Les Enfants, Stand By Me, Europa Europa, and De aanslag.

But this one is my favourite.

In Dog we shadow Ingemar – a Swedish kid deserted by luck and most of his family – as he strives not to upset anyone. The fact that he takes Laïka, first Earthling in space, as his role model, is just the first instance of his rare insight.

He needs it. His mom is dying. His family is destitute; his dad abandoned them long ago. Ingemar

and his older brother are trapped between the need to placate and care for their increasingly erratic mother and keeping the social workers at bay.

and his older brother are trapped between the need to placate and care for their increasingly erratic mother and keeping the social workers at bay.His only friend is his dog Sickan. As long as they're together, he believes, everything's OK. (Nor is he the first human to conclude that dogs are better company than people.)

Canine loyalty is a godsend for Ingemar, because notwithstanding his unfailing goodwill, he's a lightning rod for disaster. Other kids take advantage of him; adults project their fears and disappointments on him. And he just doesn't fit in. He's too happy, too game, too prone to pluck the straight laces of Cold War Stockholm. Everywhere he's told he's one too many: unsuitable, unwelcome, a jonah. Like his cosmonaut hero, he's a defenceless alien, suspended far from home in an airless hell.

And then he's blasted off to an uncle he's never met, in a rural wasteland known to cartographers as Småland. (Literally: "Small Land".)

Nevertheless, to take a page from our young friend: "it could be worse". Småland is green. The sun is soft. And the first words he hears on touching down are, "You've brought the nice weather with you!"

One would be tempted to dismiss the little village he ends up in as urban romanticism: a stable, supple community where generations live in harmony. But director Lasse Hallström seems to be pointing out that there are two ways to raise children. In Småland it's for grown-ups to take care of kids, not the other way 'round. And as the old saw would have it, the whole village is actively engaged in just that.

One would be tempted to dismiss the little village he ends up in as urban romanticism: a stable, supple community where generations live in harmony. But director Lasse Hallström seems to be pointing out that there are two ways to raise children. In Småland it's for grown-ups to take care of kids, not the other way 'round. And as the old saw would have it, the whole village is actively engaged in just that.Better still: Uncle Gunnar turns out to share the same quirky DNA as his nephew. Under his roof, Ingemar gets the adult direction he's been missing: loving, understanding, respectful of his nature.

Not that there isn't friction; this is, after all, 1958. A ringing Brigitte Bardot lookalike signals Sweden's impending sexual liberation. Girls muscle into sports. Boys mock the Church. Immigrants crowd in. TV mesmerises a neighbourhood. Tempers flare.

But then they flare out again. Nothing is that important in Småland.

Young Anton Glanzelius received a mountain of justified praise for his bodhisattva-league performance as young Ingemar. Now a television producer, he says, "I just played myself." And though actor Tomas von Brömssen caught a little criticism for his Stockholm accent, one would be hard-pressed to find a closer reading of rustic Uncle Gunnar: a carefully-measured jumble of eccentricity and responsibility.

But what truly makes

Dog is Hallström's palpable affection for children. His instinctive grasp of their perspective and mannerisms recalls François Truffaut's own kindergeist masterpiece, Argent de Poche. You'll want to hug every one of these kids. (Even Ingemar's damaged brother.)

Dog is Hallström's palpable affection for children. His instinctive grasp of their perspective and mannerisms recalls François Truffaut's own kindergeist masterpiece, Argent de Poche. You'll want to hug every one of these kids. (Even Ingemar's damaged brother.)A few critics took issue with what they perceived to be a surfeit of treacle in Hallström's vision, but the well-researched trauma symptoms subtly insinuated into Ingemar's personality attest to significant, if unspoken, darkness. (His "drinking problem", for one, is a documented neurosis of emotionally disturbed children.)

It's just that not quite everybody in his life is unreachable. Also, Ingemar has this theory about dukkha – one he's backed up with hard data:

In fact, I've been kinda lucky. I mean, compared to others. You have to compare, so you can get a little distance from things.

Like Laïka. She really must have seen things in perspective. It's important to keep a certain distance.

I think about that guy who tried to set a world record for jumping over buses with a motorcycle. He lined up 31 buses.

If he'd left it at 30, maybe he would have survived.

Until next time: keep a tight rope, droogies.

Topics:

Anton Glanzelius,

Avalokiteshvara,

bodhisattva,

dog,

dukkha,

François Truffaut,

Lasse Hallström,

movie,

review,

svenska språket,

Sweden

Thursday, 18 June 2015

Good Movie: The Way

The Way is a movie you've seen a dozen times: angry/critical/selfish/

The Way is a movie you've seen a dozen times: angry/critical/selfish/disapproving/distant father comes to regret his bullheaded incompetence at the whole human thing. It's also a movie you've never seen before, and I recommend that anyone who has a dad, or is a dad – or is a man, or knows a man – remedy that.

The plot, as I said, is well-travelled, but what saves the film from that (and sometimes itself) is its lead actor's astounding fluency in silence. If nothing else, The Way proves that if you want to make a movie about a man struck speechless by suffering, you're gonna need Martin Sheen. Guy's like the Robin Williams of stillness.

For reasons I can't reveal without spoiling, Tom Avery decides, without a lick of reflection or experience, to hike the Camino de Santiago. This ancient Christian pilgrimage route, winding through the daunting Pyrenees from one side of the Iberian Peninsula to the other, has lately become très chic among aging Boomers. But very few of them actually do it; as a range cop at the trailhead advises our hero, that takes two to three months. If you're in shape. And you have the fire.

Which Avery may; I'll leave that for viewers to discover. But in his desperate search for solitude, our man ends up, Jeremiah Johnson-style, a reluctant surrogate

father to a gaggle of young, equally wounded fellow pilgrims. The fact that he has the same prickly dynamic with them that he has with his actual son, is a bit heartbreaking. Yet, pointedly, it works. The filmmaker seems to be telling us, in hauntingly familiar tones, that eighty per cent of fatherhood is just showing up.

father to a gaggle of young, equally wounded fellow pilgrims. The fact that he has the same prickly dynamic with them that he has with his actual son, is a bit heartbreaking. Yet, pointedly, it works. The filmmaker seems to be telling us, in hauntingly familiar tones, that eighty per cent of fatherhood is just showing up.Which is particularly bittersweet, given that filmmaker Emilio Estevez, who also wrote and directed the screenplay and played Avery's son, is in fact Martin Sheen's real-life son. All told, the project involved three generations of Estevez men – father, son, and grandson – before and behind the camera.

I was bemused, while researching this review, to find most commentary about The Way on Christian sites. Thus do we chop complex realities into simplistic tropes. Yeah, hiking the Camino is a Roman Catholic thing. And yeah, Tom Avery is Catholic (as are the Estevez family). His faith is apparently one of the tools he takes into the mountains. I say "apparently" because he never utters a Christian word. Neither, come to that, does anyone else; even a priest they meet is refreshingly circumspect. Nobody totes a Bible; nobody prays, at least not formally; nobody mentions Jesus. If it weren't for Avery's briefly crossing himself during a specific repeated ritual, you'd have no idea he was a believer. In anything.

Yet mainstream outlets seem terrified of the sectarian implications of a pilgrimage, while the Christian market glommed hard onto a film with a big-name star. (The fact that many sources were Evangelical underscores the general confusion over "whose" movie this is. Estevez has verified that this was a conscious strategy on his part.) Basically, The Way is several films; sooner or later, it ends up being about everybody.

Yet mainstream outlets seem terrified of the sectarian implications of a pilgrimage, while the Christian market glommed hard onto a film with a big-name star. (The fact that many sources were Evangelical underscores the general confusion over "whose" movie this is. Estevez has verified that this was a conscious strategy on his part.) Basically, The Way is several films; sooner or later, it ends up being about everybody.But one way or the other (get it?), this is a very Buddhist film. C'mon, brothers and sisters: this whole "way-path-journey" thing is our metaphor, eh? And the Estevez spin it particularly well. I defy any Zenner, having seen The Way, to tell me it's a "Christian" movie. (And I defy any Christian to tell me it's not.)

Of course, the viewer-pilgrim is bound to get a few pebbles in his or her sandal along the road. There's a digression involving the Rom that reads like an episode from an old American TV series. The actors' raw commitment carries that off, but harder to dismiss is a subplot that plays smoking as poetic, inconsequential, even cute. It is none of those things. Hollywood is largely responsible for the perpetuation of this devastating – and goddam rude – addiction, and I earnestly wish it would grow the hell up and get over its teeny-bopper fascination with tobacco.

But the film survives this lapse, even if the character will not. Its decidedly fly- (or walk-) by-night production model delivers scene after magnetically attractive, entirely authentic scene, drenched in immediacy. Estevez has a rare gift for spotting eloquent shots, and here he's inadvertently made one of the best tourist board adverts ever. Watching it, I'm thinking, "What this trail needs is a Zen hermit monk."

Best of all is the ending, which – and here I don't think I'm giving anything away – is realistically open-ended. This reviewer gets a little weary of cinematic "happily ever after" (and its evil twin, "broken forever") outcomes. Life goes on. It's easier to relate to, and to care about, lives that continue after the credits roll.

Why we keep making this movie over and over would be an excellent topic for a doctoral thesis. Why we keep watching it is grist for meditation. I highly doubt The Way will be the last damaged-dad picture ever made. I am equally sure that while some of its successors may be as good, none will be better.

Topics:

Buddhism,

Camino de Santiago,

Christianity,

dukkha,

Emilio Estevez,

fathers,

France,

hermit practice,

Martin Sheen,

movie,

review,

Robin Williams,

Spain

Thursday, 16 October 2014

Everyone

Everyone has a room to air.

Everyone has a soul to bare.

Everyone has a horn to blare.

Everyone has a cause to care.

Everyone has a task to chair.

Everyone has a doubt to dare.

Everyone has a bent to err.

Everyone has a hull to fair.

Everyone has a flame to flare.

Everyone has a growl to glare.

Everyone has a hound to hare.

Everyone has a glove to pair.

Everyone has a call to prayer.

Everyone has a chance too rare.

Everyone has a crow to scare.

Everyone has a song to share.

Everyone has a snipe to snare.

Everyone has a coin to spare.

Everyone has a debt to square.

Everyone has a scowl to stare.

Everyone has an oath to swear.

Everyone has a page to tear.

Everyone has a road to there.

Everyone has a robe to wear.

Everyone has a soul to bare.

Everyone has a horn to blare.

Everyone has a cause to care.

Everyone has a task to chair.

Everyone has a doubt to dare.

Everyone has a bent to err.

Everyone has a hull to fair.

Everyone has a flame to flare.

Everyone has a growl to glare.

Everyone has a hound to hare.

Everyone has a glove to pair.

Everyone has a call to prayer.

Everyone has a chance too rare.

Everyone has a crow to scare.

Everyone has a song to share.

Everyone has a snipe to snare.

Everyone has a coin to spare.

Everyone has a debt to square.

Everyone has a scowl to stare.

Everyone has an oath to swear.

Everyone has a page to tear.

Everyone has a road to there.

Everyone has a robe to wear.

(Photo of Fuke Zen monk courtesy of Urashima Taro and Wikimedia Commons.)

Topics:

acceptance,

alienation,

blessing,

compassion,

depression,

dukkha,

forgiveness,

gratitude,

hermit practice,

meditation,

mindfulness,

poem,

Zen

Thursday, 31 July 2014

Good Song: Japanese Bowl

If you don't know Peter Mayer, you should know Peter Mayer. He's one of those artists (like Sherman Alexie and Regina Spektor) who deserve much wider play than they get. Peter, whose spiritual preparation is Roman Catholic, is sometimes described as a "Christian artist". I'd call his genre (if so narrow a vein can be called that) "Authentic Christian"; his faith is strong enough to be strengthened by other traditions (including Buddhist), and his work is carefully universal, accessible to all, free of recruitment slogans. He even writes a few of that kind of song that name-brand Christian musicians most detest: those with no religious content whatsoever. Just wise, witty, and fun. Well hell, you might as well listen to Judas Priest.

By way of introduction I offer the here-above. I chose this track for two reasons: it's one of the few selections from Peter's catalogue you can find on YouTube, and it perfectly encapsulates my feelings about myself. In fact, it's my new business card. From now on I'm just sending people the YouTube address, with "Hit 'reply' if these terms are acceptable" underneath.

And if any Buddhist artist has better described the relationship between dukkha and enlightenment, just you send me the link.

(By the way, this track comes off the CD Heaven Below. There is no padding anywhere on it. Just go ahead and buy it sound-unheard. You'll feel smart you did.)

JAPANESE BOWL

by Peter Mayer

I’m like one of those Japanese bowls

That were made long ago

I have some cracks in me

They have been filled with gold

That’s what they used back then

When they had a bowl to mend

It did not hide the cracks

It made them shine instead

So now every old scar shows

From every time I broke

And anyone’s eyes can see

I’m not what I used to be

But in a collector’s mind

All of these jagged lines

Make me more beautiful

And worth a much higher price

I’m like one of those Japanese bowls

I was made long ago

I have some cracks you can see

See how they shine of gold

Topics:

Buddhism,

Christianity,

dukkha,

enlightenment,

Japan,

music,

Peter Mayer,

Regina Spektor,

Sherman Alexie,

video

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)