I ran into a Zen axe-grinder on Twitter a few months ago. The experience continues to turn in my thoughts.

I didn't know this guy (I believe he was a guy; if not, my bad) but several sangha there – most of them fellow hermits – did. They just snorted when he turned up again and had little else to do with him. I initially engaged, in good eremitical faith, until he got personal – which happened quickly – and then I ignored him, too.

My brother's holy crusade had something to do with "one true path", of course, as well as a claimed apostasy of Japanese Zen in general, the crystal purity of early Chàn, and a perpetual tantrum over anyone practicing outside the narrow confines he considered "real". A major focus of his rage – and this will surprise no-one who's met the type – was a purported episode that supposedly derailed authentic Zen a thousand or more years ago, allowing evil conspirators to substitute not-Zen in its place ever since.

Part of that Gothic intrigue includes alleged documentary proof that, far from being the iconoclastic solitary we were sold, Bodhidharma was in fact a domestic church boy who kowtowed to canon authority and insisted everyone else do as well. (This would be the Zen equivalent of claiming that Jesus was a well-to-do rabbinical Pharisee.)

All of which was sardonic entertainment for those who'd heard it before; at this stage in Western Zen, we're in great majority converts recruited via informed choice and lived experience, thus there are few of this ilk among us yet. Converts tend to accept the landscape they find; self-declared revolutionaries who radically reconstruct a tradition's history are a hallmark of socially- and parentally-transmitted religion.

It's just that overthrowing the Establishment is no fun if it doesn't net you substantial power, which the Zen establishment entirely lacks in this place and time.

But if the next generation survives us, they'll see more of these people.

So I rate it prudent to reach out to the Great Sangha while the reaching's good, in the hope that younger Zen in particular may, somewhere down the sunset path, ingest a grain of scepticism in their regard.

As I've pointed out, the world already groans with churches, and if all we are is another one, we'd best disband. My Twitter brother is angry; he wants people brought down, chastised. This is churchifying, not enlightenment practice. (I'm reminded of Zenners who "debunk" my hermit practice because I have no living teacher, and even one who met my suggestion that Zen is about sitting rather than service with "Sounds like Mara." Next up: our very own Satanic Panic!)

So they exist, even in Western Zen. And let's face it: to some extent, we are all them. Everyone has that line that must not be crossed, that "Zen is here, not there" litmus spell. If you don't acknowledge it, and atone for it, you're the death of Zen.

There's a cogent Quaker teaching that addresses this issue: "The only way to defeat the Devil is to stop being him." (I hope the maraphobe above also encounters this instruction at some point.)

I intend to use the example of my angry fellow traveller to locate him in myself, remind him why we've given our life to this Zen thing, and whack myself with the invisible kyôsaku I carry for the purpose.

Because this shit is a waste of energy, in all religions, at all times.

(Portrait of Bodhidarma courtesy of Rawpixel.com and a generous photographer.)

Thursday, 30 November 2017

Benedictine Kyôsaku

"If someone would ask me, 'Who is the more important one, Jesus or Buddha?', I would say, 'You are the most important one.'"

"If someone would ask me, 'Who is the more important one, Jesus or Buddha?', I would say, 'You are the most important one.'"Brother David Steindl-Rast, Zen-trained Benedictine monk.

(Photo of the Benedictine brothers of St. Benedict's Abbey, Atchison, Kansas, demonstrating proper monastic attitude courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Thursday, 21 April 2016

The Koan of Tradition

An aspect of Meditation in the Wild (Rusty Ring review here) that I greatly appreciated was author Charles S. Fisher's relentless pursuit of verifiable history in our practice models. This, as he points out, is hard to come by, given the piecemeal nature of early Buddhist documentation. Nevertheless, Fisher found many thought-provoking differences between current teaching and historical fact; I listed several in my review.

But I left out the most compelling, for more thorough consideration later:

The Shakyas, Fisher says, had no king.

Let that settle in for a minute. This is the approximate Buddhist equivalent of saying that Christ wasn't poor. It throws shade on a central element of our world view, and poses some provocative questions.

And as it turns out, my brother Charles was precise: not only were Gautama's people – a northern nation called the Shakyas – democratic, they weren't even Brahmins. In other words, the entire Buddhic origin story is false; Gautama was not in fact a prince. Nor was he a member of the immutable, unattainable Indian overclass. He was probably a Kshatriya, that is, an ordinary citizen, albeit at the top of the common heap.

Per Palikannon.com:

This inconvenient truth may well be a gift, that employing authentic Zen don't-know-mind will smelt into usable gold. Therefore, may I respectfully suggest we question ourselves on this matter – without, as is our practice, answering – in the following vein:

And so on.

Peace and progress to the nation of seekers.

(Photo of morning in Kapilavastu, Nepali city of the Buddha's birth, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

But I left out the most compelling, for more thorough consideration later:

The Shakyas, Fisher says, had no king.

Let that settle in for a minute. This is the approximate Buddhist equivalent of saying that Christ wasn't poor. It throws shade on a central element of our world view, and poses some provocative questions.

And as it turns out, my brother Charles was precise: not only were Gautama's people – a northern nation called the Shakyas – democratic, they weren't even Brahmins. In other words, the entire Buddhic origin story is false; Gautama was not in fact a prince. Nor was he a member of the immutable, unattainable Indian overclass. He was probably a Kshatriya, that is, an ordinary citizen, albeit at the top of the common heap.

Per Palikannon.com:

The Sākyans evidently had no king. Theirs was a republican form of government, probably with a leader, elected from time to time. The administration and judicial affairs of the gotta [clan] were discussed in their Santhāgāra…(Note that final word, which clearly shares etymology with "sangha".)

This inconvenient truth may well be a gift, that employing authentic Zen don't-know-mind will smelt into usable gold. Therefore, may I respectfully suggest we question ourselves on this matter – without, as is our practice, answering – in the following vein:

- How does our renewed knowledge of the Buddha's true origins change our understanding of his perspectives and motivations?

- Why did we change the story?

- What does it mean that we changed the story?

- How does the factual version challenge us?

- Scare us?

- Uplift us?

- How about the mythical version?

- Are we required to correct this misconception?

- In what ways might the "enhanced" story endanger authentic practice?

- Can facts endanger authentic practice?

- Can both versions coexist in our practice?

- If so, how?

- If not, what are we called to do, as individual Zenners?

- Is this a problem?

And so on.

Peace and progress to the nation of seekers.

(Photo of morning in Kapilavastu, Nepali city of the Buddha's birth, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and a generous photographer.)

Thursday, 29 October 2015

Matthew 6:6

For some time now I've wanted to write The Big Book of Un-Preached Sermons, a disquisition on the Shadow Gospel: that body of Christic teaching that remains largely unknown to lay Christians, owing to surgical inaction by church leaders.

For some time now I've wanted to write The Big Book of Un-Preached Sermons, a disquisition on the Shadow Gospel: that body of Christic teaching that remains largely unknown to lay Christians, owing to surgical inaction by church leaders.It's a remarkably large canon.

My all-time favourite constituent, and one that continues to be a cornerstone of my Zen practice, is Matthew 6:6:

But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly.I've never heard any clerical commentary on this directive. Reasons aren't hard to divine; Christian militants often use public prayer as a form of demonstration, even confrontation. Some will performance-pray at the drop of a hat, and given the chance, force it into public spaces and government proceedings. These people don't even seem to own a closet, let alone know how to use it.

Sadly, their detractors seldom include other Christians. At least not ones objecting on doctrinal grounds. Still, the Christ of Matthew is categorical: prayer is not prayer when others can see it.

It's not a minor point. What's at issue is nothing less that the total undoing – or at least the not-doing – of the central practice Jesus gave his disciples.

Speaking of central practices, you know what else is not itself in public?

Meditation.

I've held forth many times (here and here and here and here and here) on the strange fact that Buddhism – a solitary eremitical religion founded by the solitary eremitical Buddha – has become a pyramid scheme, to the point that actual Buddhic practitioners are now viewed as heretics. Strangest of all is the contention that the only "real" practice is collective. Authentic zazen, I'm assured, only happens when you sit with others – the more, the better. I've also been informed that the solitary sesshins I sit four times a year… aren't. Same rationale: it's only meditation if someone else is watching.

The greatest danger of this hokum is not that it reverses the Buddha's teaching and lifelong example. It's that it's crap.

I've meditated in public. I was a committed Zen centre member for several years, during which I sat formal zazen in the zendo with the assembled sangha at least twice a week. Even as a hermit, I sometimes sit in circumstances where passersby may, uh… pass by. And I'm here to tell you that the moment onlookers – or even the possibility of onlookers – enter the mix, meditation goes right out the window. Now you're playing "look-how-Zen-I-am": all posture and reputation and approval. That's not practicing. It's acting.

Jesus got this. The instant others see you praying, you stop talking to God and start talking to them. In fact, you start lying to them, about talking to God. You pile sin on top of apostasy on top of wasted effort.

It's true that diligent practice can overcome this: I once experienced kensho at the end of a zendo sesshin. I stopped caring about the opinions of peers and entered a state of unselfed clarity for a few hours. But it wasn't any deeper than the kensho I've experienced alone, and the presence of others was an impediment to it, not a catalyst.

I believe collective zazen, like collective prayer, can be a valid form. It rarely accomplishes the goals of Buddhic practice, but it may achieve others that, though less vital, are nonetheless worthwhile. (It can build community and shore up personal resolve.)

However, when public displays of communion are weaponised – when they're used to intimidate or indoctrinate – then the sangha must step up and restore right action.

(The Anchorite, by Franciszek Ejsmond, courtesy of the Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thursday, 9 April 2015

The Dirty-Clothes Problem: White Trash Buddhist

The just-past issue of Tricycle magazine carried one of the most important articles to come out in the Buddhist press in a generation. Written by my brother Brent R. Oliver, the fact that the title alone (White Trash Buddhist) provokes laughter in many quarters is proof of concept.

The just-past issue of Tricycle magazine carried one of the most important articles to come out in the Buddhist press in a generation. Written by my brother Brent R. Oliver, the fact that the title alone (White Trash Buddhist) provokes laughter in many quarters is proof of concept. For the betterment of the worldwide sangha I'm going to do what they tell writers never to do: send you off-site. The Tricycle website makes Brent's thoughts available only to subscription holders (an ironic if business-savvy twist), but one of those subscribers had the good Buddhist sense to repost it for the rest of us. Therefore, in respect for magazine and writer, I will avoid multiplicating the text all over the Enlightenment Superpath and simply link to that post. Please read it and return for my comments, below.

White Trash Buddhist, by Brent R. Oliver. Tricycle, Winter 2014.

Some thoughts:

- I never felt obligated to pay at my Zen centre, and sometimes I didn't; my teacher was very generous that way. But I still felt like a schmuck, given the inevitable pay-to-pray emphasis in Western Buddhism. I fantasised I'd strike it rich someday, having made my fortune in Zen renunciation, and donate a million dollars in back payments and interest. The fact is, having an institution means planting your lotus in that dirty money-water. The Buddha said it's possible to keep your petals clean even so, if you practice hard enough; Christ flatly cautioned us not to try. Either way, in the great rock-paper-scissors of this life, dollar usually trumps Dharma.

- Brent skirts but does not delve into the effect all this money-think has on the organised sangha. I vividly remember a woman who drove hours to Zen centre in order to join us in sesshin the next morning. She watched me (a resident) arrive from work, overalls and meshback cap covered in sawdust and glue, with clear alarm. As I tugged off my steel-toed safety boots I explained that I punched a clock at a local factory. Soon after, she ran – presumably screaming – out the door, and we never saw her again.

There were undoubtedly other factors in her reaction, mostly relative to her own past and expectations, but the unpretty sight of my blue-collar arse visibly disturbed her. Which is ridiculous. And unBuddhist. And standard in Western Zen. - Brent also appears to need a teacher; his objections to the financial status quo rest on the expense of that relationship. Chances are he's not a hermit. (That is, not even one who doesn't realise it.) Eremitical monasticism is not for all, or even many. Hermits are weird; we'd already been weird for thousands of years the day the Buddha joined us. But I'd love to sit down with my brother over tea and discuss his options. It'd be a damned shame (no pun intended) if he left the path entirely, when there are alternatives that might resolve, in whole or in part, his suffering.

One way or the other, I wish him the best. He's right; Buddhism in the West has become a comfortable little bourgeois club, where we share organic snacks, indulge in exotic Asian choreography, and expect – nay, oblige – tidy little professional values. Ironic, given our hippy origins, but our religious institutions have turned out, all these years later, in many instances, to be so many little boxes.

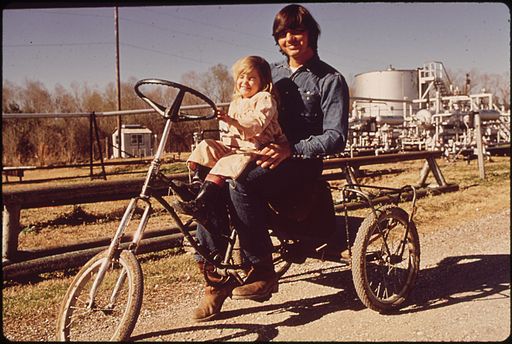

(Photo of a working man riding his daughter on a homemade tricycle, courtesy of John Messina, the US Environmental Protection Agency, and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thursday, 15 January 2015

Shock and Awe

One of my Franciscan brothers in Québec, a friar named Henri, presented seminars on Christian practice to groups of Catholic seniors – of which he was one. He spoke on many topics, but his most popular lesson began with him passing out polished rocks purchased at the dollar store. He then read the opening verses of John 8 – the oft-quoted and roundly ignored Gospel passage wherein Jesus intervenes in the case of a convicted adulteress, subject under law to death by stoning. "He that is without sin among you," he says, "let him first cast a stone at her." From there Henri brought the teaching forward, pointing out at last that we all possess the Christ-like power of not-throwing.

One of my Franciscan brothers in Québec, a friar named Henri, presented seminars on Christian practice to groups of Catholic seniors – of which he was one. He spoke on many topics, but his most popular lesson began with him passing out polished rocks purchased at the dollar store. He then read the opening verses of John 8 – the oft-quoted and roundly ignored Gospel passage wherein Jesus intervenes in the case of a convicted adulteress, subject under law to death by stoning. "He that is without sin among you," he says, "let him first cast a stone at her." From there Henri brought the teaching forward, pointing out at last that we all possess the Christ-like power of not-throwing.Henri was a quiet-spoken man, with a gift for landing a point, and he quickly became famous across the province as « le gars qui fait le truc avec les cailloux » ("the guy who does that thing with the rocks"). His main point was that we all carry a rock through this life, and whereas throwing it is a mean and menial act, not-throwing it amounts to a kind of superpower; in a world where we have virtually no agency, we can always do this, to devastating effect. And no-one can stop us.

At the end of the seminar Henri sent everyone's stone home with them, as a reminder of their potential for violence, and their power to contradict it. (On a touching note, some attendees, aware that the Church in Québec is in financial distress, tried to give theirs back, so he could use it in another talk. Henri assured them the Church could still afford rocks, and they'd do greater service to keep it and remember why.)

Proof of Henri's impact came when he encountered former participants, often years later. Many told him they still had their rock, on their dresser, night stand, bathroom or kitchen counter, or dashboard. More than one reached into a purse or pocket and produced the very one; they'd carried it with them everywhere since that day.

I thought then, and I think still, that weaponising not-throwing is a remarkably Zen concept. And so I share it with you today. Indeed, I say we go Henri one better: let us each not-carry a proper Zen stoneless stone through this delusional world, and not-fling it with blockbusting shock and awe at the drop of a hat.

(Photo courtesy of Adrian Pingstone and Wikimedia Commons.)

Wednesday, 26 November 2014

Good Song: Was It Ever Really Mine

I collect Authentic Christian Pop artists, that is, devout Christians whose lyrics centre on practical application of Christ's values, rather than skin-deep commercials. They're damn thin (so to speak) on the ground, but every one I've found so far is brilliant. Inspired by fundamental truth, their work has universal appeal, and practitioners of this tiny genre work mindfully to keep it that way. Is it an effective strategy? Well, Zen Buddhist hermits love their stuff. So you tell me.

Jon Troast is a great example. Check out, by way of appropriate Thanksgiving meditation, his Was It Ever Really Mine:

This charming footage was shot at one of Jon's famous living room concerts. (He travels the US, Bashō-like, and performs for any private citizen who comes up with the pittance he charges. Yes, I'm serious: book him here.) The sound quality suffers from impromptu technology, but the album cut is crystal-clear and professionally mixed and can be streamed in the "Launch Music" device in the upper left corner of his website. Alternatively, you can GET THE ENTIRE ALBUM FREE simply by joining Jon's email list. (A $10 US value, by the way.) I have no idea how this guy stays in business, or why he's not on the charts, but perhaps we can contribute to both.

One way or another, it's one more thing to be thankful for.

WAS IT EVER REALLY MINE

By Jon Troast

I brought a dollar to the store today

Wanted to buy something new

I put the dollar in my front pocket

And brought it back home to you

‘Cause I don’t want to buy what I don’t need

And I don’t want to own what I can’t keep

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

I made a dollar at my job today

I show up every week

I guess I really didn’t make it

They gave it to me

‘Cause I don’t want to buy what I don’t need

And I don’t want to own what I can’t keep

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

There are mansions waiting in the sky

Where the rivers run but never run dry

There are highways of gold, room for this soul

I don’t think Jesus would lie

I put a dollar in the mail today

I hope it gets there in time

They look so hungry on my TV

I hope they’ll be alright

‘Cause the store’s full of things that I don’t need

And the world’s full of mouths that I can’t feed

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

And I don’t want to buy what I don’t need

And I don’t want to own what I can’t keep

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

Jon Troast is a great example. Check out, by way of appropriate Thanksgiving meditation, his Was It Ever Really Mine:

This charming footage was shot at one of Jon's famous living room concerts. (He travels the US, Bashō-like, and performs for any private citizen who comes up with the pittance he charges. Yes, I'm serious: book him here.) The sound quality suffers from impromptu technology, but the album cut is crystal-clear and professionally mixed and can be streamed in the "Launch Music" device in the upper left corner of his website. Alternatively, you can GET THE ENTIRE ALBUM FREE simply by joining Jon's email list. (A $10 US value, by the way.) I have no idea how this guy stays in business, or why he's not on the charts, but perhaps we can contribute to both.

One way or another, it's one more thing to be thankful for.

WAS IT EVER REALLY MINE

By Jon Troast

I brought a dollar to the store today

Wanted to buy something new

I put the dollar in my front pocket

And brought it back home to you

‘Cause I don’t want to buy what I don’t need

And I don’t want to own what I can’t keep

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

I made a dollar at my job today

I show up every week

I guess I really didn’t make it

They gave it to me

‘Cause I don’t want to buy what I don’t need

And I don’t want to own what I can’t keep

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

There are mansions waiting in the sky

Where the rivers run but never run dry

There are highways of gold, room for this soul

I don’t think Jesus would lie

I put a dollar in the mail today

I hope it gets there in time

They look so hungry on my TV

I hope they’ll be alright

‘Cause the store’s full of things that I don’t need

And the world’s full of mouths that I can’t feed

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

And I don’t want to buy what I don’t need

And I don’t want to own what I can’t keep

And if I’m gonna have to leave it all behind

Was it ever really mine?

Thursday, 8 May 2014

Hermits Wanted

We need hermits. OK, it's a self-serving point. But trust me: leave it to the priests and temples alone, and they'll botch this thing.

Corporate religion always warps the founder's teachings, which invariably urge individual atonement and transcendence, into a trophy-collecting expedition. Hence the uniform, the command structure, and the litmus.

That last conjures enemies. Collective religion needs these, and it needs them everywhere.

That's why we always live on the brink of Revolution, the great cosmic victory, prophesied of old, that will literally change the universe. (And will somehow be brought about by us microbes, through our thunderous obedience.) Every generation, in all ages, lives in the End Times.

At least our Zen jihad is usually a personal one. We've resisted second-comings and arhats, and at least in the West, our politics are generally not diametrically opposed to the Buddha's. But dungeons and dragons lurk even here. In Zen centres I've heard praise of "relics" (including "relics of the Buddha", a phrase my hermit tongue cannot pronounce), and breathless accounts of what must honestly be called sainthood, attributed to Thich Nhat Hanh, Seung Sahn, Suzuki-roshi, and any number of local gurus. These teachers would, I am heartened to think, quash such talk, yet the craving for deities remains. Can charisma be far behind?

The danger is real. One has only to consider Christianity, now so buried in augury, Bible-babble, and gothic conspiracy that Christ himself has lost all credibility in the larger culture. In such times a Christian hermit, churched by the Spirit alone, might preach at risk of his life.

Fortunately, we Zenners do little scripturalising. We seldom declaim verses on one another, even when we work violence on one another, and since World War II have not lawyered obscure sutras into cynical stratagems.

But we do live constantly on the verge of "enlightenment", which state we could immediately reach if only we would submit more completely to another person's will. We kick others for eating meat, for having sex, for breaching the latest liberal shibboleth. We kick ourselves, too: for not sitting enough, or right; for losing our temper, or our faith; for giving – or bearing – too little. And most wretched of all: for honouring our own nature over ordained authority. And in that we are precisely identical to every other church on this blue planet: turning away from our liberating practice, and embracing comfortable conventions.

And so we need hermits – a sunburned dervish, a naked fakir, a hemp-haired Hebrew prophet – to remind us what practice really is, and the true nature of enlightenment. Therefore (one sec while I pull on some sackcloth…) say I unto ye:

Hear me, O Zion! It happens when it happens. You can't make it happen, you can't predict when it happens, and you probably won't even know when it happens. But happen it will. On its own and by its own, with you or without you, because of you and in spite of you, whether it vindicates you or shows you for a fool.

And let's cut the crap: it's gonna show you for a fool.

All peace and success to the Nation of Seekers.

(Photo of Katskhi Pillar courtesy of ლევან ნიორაძე and Wikimedia Commons.)

Thursday, 12 December 2013

Buddha is the Reason for the Season

Know any Scrooge-sans? You know, Zenners who pout all December because it's Christmas and they're not Christian. If so, you might point out that Christmas is a secular holiday thousands of years old, bent to religious ends by the Druids and their contemporaries, long before Christians got their prideful hands on it.

But some sangha just have a giant chip on their shoulder about the Church, and so become the jutting jaw we hear about every year in the carol. You know: "Four colleybirds, three French hens, two turtle doves, and a big honkin' juttin' Zen jaw." In so doing, they surrender all Yule to a fanatical fringe that speciously demands ownership of it, and their own religious convictions to crass competition.

We Boreals have a deep physiological need to confront the terrifying cold and black of Dark Solstice, and so the symbols of light and fire, of evergreen, ever-living, winter-fruiting vegetation, and general contempt of death and fear, crop up repeatedly throughout our hemisphere. It's perfectly logical to find religious significance in natural phenomena, the only indisputable scripture there is. That's why Rohatsu – marking the time the Buddha sat under a symbol of the cosmos for eight days straight and was reborn in the laser light of the morning star – is in December. The Jews commemorate a lamp that burned for eight days without oil; Greeks and Romans sacrificed to the Harvest God, who dies every year and is reborn the next. And Christians celebrate the birth of their Saviour – bringer of light, defeater of death – though he was actually born in March.

In other words, they celebrate the effect of Christ's coming, not its fact, but sadly that's more insight than many contemporary Christians can muster. And so they've made the Season of Peace a battleground. "Jesus is the reason for the season!" is not a cry of gratitude; it's a rebuke to people who take their kids to see Santa Claus.

So it's game, point, and match to sanctimony. But wait, here's Team Zen, taking the ice! Will they make this a game?

No.

Some Zenners campaign to remove Christmas trees from airports; razor Christ-themed carols from school "Winter" concerts; even ban Santa from the mall. (I don't even know where to start with those.) Others just wall themselves up in their little cells and chant loudly in fake Chinese to fend off any errant strains of Bing Crosby that might filtre through their double-glazing.

This in spite of the fact that Christmas is the most Buddhist of holidays; arguably more, actually, than it ever was Christian. It's Sekitō Kisen all over again:

Darkness is a word for merging upper and lower,

light is an expression for distinguishing pure and defiled.

The four gross elements return to their own natures like a baby taking to its mother:

fire heats, wind moves, water wets, earth is solid;

eye and form, ear and sound, nose and smell, tongue and taste—

thus in all things the leaves spread from the root.

The whole process must return to the source.

Noble and base are only manners of speaking;

right in light there is darkness but don’t confront it as darkness,

right in darkness there is light but don’t see it as light.

Light and dark are relative to one another like forward and backward steps.

Read this chant – possibly for a first honest time – and tell me it ain't a fair-dinkum Zen Christmas carol.

The only reasonable Zen response to the ancient rite of Jul is acceptance. Acceptance of its universal origin; of its truth; and crucially, of the Dharma, which clearly passes right down the middle of it.

We are in the delusion-slashing business. I respectfully suggest we apply those skills, now they are more vital than usual, to restoring the true meaning of – and demilitarising – Christmas.

May we look deeply, every one.

(Photo of Irish Christmas card courtesy of Shirley Wynne and Wikimedia Commons, from an album of Christmas cards collected by Georgina Pim of Crosthwaite Park, Dun Laoghaire, Dublin, between 1881 and 1893.)

But some sangha just have a giant chip on their shoulder about the Church, and so become the jutting jaw we hear about every year in the carol. You know: "Four colleybirds, three French hens, two turtle doves, and a big honkin' juttin' Zen jaw." In so doing, they surrender all Yule to a fanatical fringe that speciously demands ownership of it, and their own religious convictions to crass competition.

We Boreals have a deep physiological need to confront the terrifying cold and black of Dark Solstice, and so the symbols of light and fire, of evergreen, ever-living, winter-fruiting vegetation, and general contempt of death and fear, crop up repeatedly throughout our hemisphere. It's perfectly logical to find religious significance in natural phenomena, the only indisputable scripture there is. That's why Rohatsu – marking the time the Buddha sat under a symbol of the cosmos for eight days straight and was reborn in the laser light of the morning star – is in December. The Jews commemorate a lamp that burned for eight days without oil; Greeks and Romans sacrificed to the Harvest God, who dies every year and is reborn the next. And Christians celebrate the birth of their Saviour – bringer of light, defeater of death – though he was actually born in March.

In other words, they celebrate the effect of Christ's coming, not its fact, but sadly that's more insight than many contemporary Christians can muster. And so they've made the Season of Peace a battleground. "Jesus is the reason for the season!" is not a cry of gratitude; it's a rebuke to people who take their kids to see Santa Claus.

So it's game, point, and match to sanctimony. But wait, here's Team Zen, taking the ice! Will they make this a game?

No.

Some Zenners campaign to remove Christmas trees from airports; razor Christ-themed carols from school "Winter" concerts; even ban Santa from the mall. (I don't even know where to start with those.) Others just wall themselves up in their little cells and chant loudly in fake Chinese to fend off any errant strains of Bing Crosby that might filtre through their double-glazing.

This in spite of the fact that Christmas is the most Buddhist of holidays; arguably more, actually, than it ever was Christian. It's Sekitō Kisen all over again:

Darkness is a word for merging upper and lower,

light is an expression for distinguishing pure and defiled.

The four gross elements return to their own natures like a baby taking to its mother:

fire heats, wind moves, water wets, earth is solid;

eye and form, ear and sound, nose and smell, tongue and taste—

thus in all things the leaves spread from the root.

The whole process must return to the source.

Noble and base are only manners of speaking;

right in light there is darkness but don’t confront it as darkness,

right in darkness there is light but don’t see it as light.

Light and dark are relative to one another like forward and backward steps.

Read this chant – possibly for a first honest time – and tell me it ain't a fair-dinkum Zen Christmas carol.

The only reasonable Zen response to the ancient rite of Jul is acceptance. Acceptance of its universal origin; of its truth; and crucially, of the Dharma, which clearly passes right down the middle of it.

We are in the delusion-slashing business. I respectfully suggest we apply those skills, now they are more vital than usual, to restoring the true meaning of – and demilitarising – Christmas.

May we look deeply, every one.

(Photo of Irish Christmas card courtesy of Shirley Wynne and Wikimedia Commons, from an album of Christmas cards collected by Georgina Pim of Crosthwaite Park, Dun Laoghaire, Dublin, between 1881 and 1893.)

Thursday, 3 May 2012

How Christian Is Your Cat?

Christopher Smart (1722 – 1771) is a bit of a cipher. A BritLit staple, he lived the sort of life usually associated with poets: haphazard, profligate, and well-disastered. Late in life he became a Christian mystic. From that point forward his work suggests a religious practice strongly analogous to modern eremitical monasticism: he continued to live in society, but fixated on the imprint of God in all things.

He was also locked up in a lunatic asylum, until influential friends got him sprung.

Was my brother Christopher mentally ill? Hermits have been so accused, under whatever Everyone Knows To Be True at the time, since the first of us declared. By reliable report, Smart exhibited a few classic symptoms of bipolar disorder, a condition highly correlated with religious calling. But he lacked others that are equally determinant.

I stand with Jesus on this one: if a guy's work is legit, so is he. And while Smart's devotional meditations do contain tics, they are coherent, technically masterful, and incisive. They're also funny, ironic, and self-mocking, attributes rarely encountered in psychotic rants.

Check out his analysis of the koan, "Is my cat saved?". (See below.) Smart wrote this in the asylum, with research assistance from his sole friend and companion, Jeoffry.

It's long. Read it anyway. See if you too are not hooked like a catfish by the third line.

Jubilate Agno, Fragment B, 4 (excerpt)

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For is this done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his fore-paws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the fore-paws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For Sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For Seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For Eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For Ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For Tenthly he goes in quest of food.

For having consider’d God and himself he will consider his neighbour.

For if he meets another cat he will kiss her in kindness.

For when he takes his prey he plays with it to give it chance.

For one mouse in seven escapes by his dallying.

For when his day’s work is done his business more properly begins.

For he keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin and glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life.

For in his morning orisons he loves the sun and the sun loves him.

For he is of the tribe of Tiger.

For the Cherub Cat is a term of the Angel Tiger.

For he has the subtlety and hissing of a serpent, which in goodness he suppresses.

For he will not do destruction, if he is well-fed, neither will he spit without provocation.

For he purrs in thankfulness, when God tells him he’s a good Cat.

For he is an instrument for the children to learn benevolence upon.

For every house is incompleat without him and a blessing is lacking in the spirit.

For the Lord commanded Moses concerning the cats at the departure of the Children of Israel from Egypt.

For every family had one cat at least in the bag.

For the English Cats are the best in Europe.

For he is the cleanest in the use of his fore-paws of any quadrupede.

For the dexterity of his defence is an instance of the love of God to him exceedingly.

For he is the quickest to his mark of any creature.

For he is tenacious of his point.

For he is a mixture of gravity and waggery.

For he knows that God is his Saviour.

For there is nothing sweeter than his peace when at rest.

For there is nothing brisker than his life when in motion.

For he is of the Lord’s poor and so indeed is he called by benevolence perpetually – Poor Jeoffry! poor Jeoffry! the rat has bit thy throat.

For I bless the name of the Lord Jesus that Jeoffry is better.

For the divine spirit comes about his body to sustain it in compleat cat.

For his tongue is exceeding pure so that it has in purity what it wants in musick.

For he is docile and can learn certain things.

For he can set up with gravity which is patience upon approbation.

For he can fetch and carry, which is patience in employment.

For he can jump over a stick which is patience upon proof positive.

For he can spraggle upon waggle at the word of command.

For he can jump from an eminence into his master’s bosom.

For he can catch the cork and toss it again.

For he is hated by the hypocrite and miser.

For the former is affraid of detection.

For the latter refuses the charge.

For he camels his back to bear the first notion of business.

For he is good to think on, if a man would express himself neatly,

For he made a great figure in Egypt for his signal services.

For he killed the Ichneumon-rat very pernicious by land.

For his ears are so acute that they sting again.

For from this proceeds the passing quickness of his attention.

For by stroaking of him I have found out electricity.

For I perceived God’s light about him both wax and fire.

For the Electrical fire is the spiritual substance, which God sends from heaven to sustain the bodies both of man and beast.

For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.

For, though he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face of the earth are more than any other quadrupede.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the musick.

For he can swim for life.

For he can creep.

(Ed. note: "creep" here means crawl.)

He was also locked up in a lunatic asylum, until influential friends got him sprung.

Was my brother Christopher mentally ill? Hermits have been so accused, under whatever Everyone Knows To Be True at the time, since the first of us declared. By reliable report, Smart exhibited a few classic symptoms of bipolar disorder, a condition highly correlated with religious calling. But he lacked others that are equally determinant.

I stand with Jesus on this one: if a guy's work is legit, so is he. And while Smart's devotional meditations do contain tics, they are coherent, technically masterful, and incisive. They're also funny, ironic, and self-mocking, attributes rarely encountered in psychotic rants.

Check out his analysis of the koan, "Is my cat saved?". (See below.) Smart wrote this in the asylum, with research assistance from his sole friend and companion, Jeoffry.

It's long. Read it anyway. See if you too are not hooked like a catfish by the third line.

Jubilate Agno, Fragment B, 4 (excerpt)

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For is this done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his fore-paws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the fore-paws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For Sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For Seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For Eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For Ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For Tenthly he goes in quest of food.

For having consider’d God and himself he will consider his neighbour.

For if he meets another cat he will kiss her in kindness.

For when he takes his prey he plays with it to give it chance.

For one mouse in seven escapes by his dallying.

For when his day’s work is done his business more properly begins.

For he keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin and glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life.

For in his morning orisons he loves the sun and the sun loves him.

For he is of the tribe of Tiger.

For the Cherub Cat is a term of the Angel Tiger.

For he has the subtlety and hissing of a serpent, which in goodness he suppresses.

For he will not do destruction, if he is well-fed, neither will he spit without provocation.

For he purrs in thankfulness, when God tells him he’s a good Cat.

For he is an instrument for the children to learn benevolence upon.

For every house is incompleat without him and a blessing is lacking in the spirit.

For the Lord commanded Moses concerning the cats at the departure of the Children of Israel from Egypt.

For every family had one cat at least in the bag.

For the English Cats are the best in Europe.

For he is the cleanest in the use of his fore-paws of any quadrupede.

For the dexterity of his defence is an instance of the love of God to him exceedingly.

For he is the quickest to his mark of any creature.

For he is tenacious of his point.

For he is a mixture of gravity and waggery.

For he knows that God is his Saviour.

For there is nothing sweeter than his peace when at rest.

For there is nothing brisker than his life when in motion.

For he is of the Lord’s poor and so indeed is he called by benevolence perpetually – Poor Jeoffry! poor Jeoffry! the rat has bit thy throat.

For I bless the name of the Lord Jesus that Jeoffry is better.

For the divine spirit comes about his body to sustain it in compleat cat.

For his tongue is exceeding pure so that it has in purity what it wants in musick.

For he is docile and can learn certain things.

For he can set up with gravity which is patience upon approbation.

For he can fetch and carry, which is patience in employment.

For he can jump over a stick which is patience upon proof positive.

For he can spraggle upon waggle at the word of command.

For he can jump from an eminence into his master’s bosom.

For he can catch the cork and toss it again.

For he is hated by the hypocrite and miser.

For the former is affraid of detection.

For the latter refuses the charge.

For he camels his back to bear the first notion of business.

For he is good to think on, if a man would express himself neatly,

For he made a great figure in Egypt for his signal services.

For he killed the Ichneumon-rat very pernicious by land.

For his ears are so acute that they sting again.

For from this proceeds the passing quickness of his attention.

For by stroaking of him I have found out electricity.

For I perceived God’s light about him both wax and fire.

For the Electrical fire is the spiritual substance, which God sends from heaven to sustain the bodies both of man and beast.

For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.

For, though he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face of the earth are more than any other quadrupede.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the musick.

For he can swim for life.

For he can creep.

(Ed. note: "creep" here means crawl.)

Thursday, 17 November 2011

The Capital Punishment Koan

But the good news is I did change my heart. It just took a while to generate the will. And that's my right. I also get better at this stuff. And that's all God asks. Live this moment right; the past is his property. I am no different from everything else: I'm not what I was. And I'm not even what I've done. That was the koan Gautama gave to Angulimala, the serial killer who became his disciple. All you have to do to please God is strive. He accepts all progress, even that which is invisible to others, even that which is invisible to you, as full payment. That's why we live so many lives. In point of fact, we live as many lives as it takes. All of us. No Heart Left Behind. Fudo closes the door on an empty room. That's his vow.

But the good news is I did change my heart. It just took a while to generate the will. And that's my right. I also get better at this stuff. And that's all God asks. Live this moment right; the past is his property. I am no different from everything else: I'm not what I was. And I'm not even what I've done. That was the koan Gautama gave to Angulimala, the serial killer who became his disciple. All you have to do to please God is strive. He accepts all progress, even that which is invisible to others, even that which is invisible to you, as full payment. That's why we live so many lives. In point of fact, we live as many lives as it takes. All of us. No Heart Left Behind. Fudo closes the door on an empty room. That's his vow.And by this truth, capital punishment is not just technically murder, it's the random, joyful murder of serial killers. You never kill the man who killed; every criminal executed is innocent, and that would be the case even if you crucified him the very night. Admittedly, that point is academic. But when you kill a man who has lived twenty more years, suffering in the man-made Hell of prison, you are not only killing a complete stranger, you're often killing a soul seared generous and kind in a fire you set. So don't come snivelling around here with your "eye for an eye;" you've taken a soul for an eye.

Hence the koan of capital punishment: Whose soul have you taken?

Wu Ya's commentary: "Not mine. Anybody missing a soul?"

(Adapted from "100 Days on the Mountain," copyright RK Henderson. Photo courtesy of WikiMedia and Rafael Pi Belda [photographer].)

Friday, 11 February 2011

Bite Me, Batman!

|

Candid portrait of my practice: written and recorded teachings; twine and rings for making fudos; mat where my bowl rests; laptop, sole link with the outside. |

Christ and the Buddha defined monastics in astoundingly similar terms: They answer a unique call and walk a personal path. They reject personal ambition, and family and social obligation. Though encouraged to seek each other out for wisdom and solace, they are self-ordained. Neither Jesus nor Gautama recognised any other clerical model.

Such renunciates are called monks, from the morpheme mono-, meaning "single."

Unfortunately, as individuals who follow a personal call and have no use for human authority or the credentials it sells, we quickly fell afoul of power. As a result, The Man redefined the word as "one who lives in a monastery," that is, a "place where people are alone together." (Hey, don't look at me.) Monasteries are owned and operated by The Establishment, which claims sole right to train and ordain residents. Let's be clear: there is no scriptural basis for this presumption, or this practice.

Today, ordained monastics have all but wiped alternatives from memory, so that an old-school monk like me risks being labelled a fraud for claiming the title. But I do anyway.

Later we stick-and-sandal types took the term hermit, by way of clearing up the confusion, but this too has become problematic. For starters, it calls up images of a crotchety old man who hates people and lives in the woods and never bathes. And I'm not that crotchety.

By whatever name, monastics who live by a rule of their own authorship have been around since the first human suspected there was more to life than the opposable thumb. To my certain knowledge, only the Roman Catholic church recognises us officially today. And the Vatican has been under pressure to ordain us ever since, but so far, successive popes have defended the eremitic vocation.

I confess I'm a bit envious of my Catholic brothers and sisters. Thanks to papal protection, there is now a sanctioned hermit movement within the Church that helps to dampen, if not eradicate, the sniping. Most Catholics I meet have still never heard of us, but the ordained monastics have, and that's huge.

Zen, sadly, is another matter. Although one of the most hermit-bound traditions on earth, the current Zen establishment is largely hostile to free-range monks. It's koanic, really: the Buddha was a hermit; Bodhidharma was a hermit; Huineng, father of all extant Zen lineages, was arguably a hermit; Ryōkan, one of our most beloved ancestors, was a hermit; Ikkyū, whose teachings are an essential antidote to Buddhist hypocrisy, was a hermit. But the Asian cultures in which Zen is rooted have a demonstrable contempt for individual initiative, and that has led us into a cul-de-sac of guru-worship. Today, Zen hermits are often accused of imposture and egotism for living the Buddha's own given precepts. The resentment is mutual and conspicuous, particularly in the West, where autocracy is dimly viewed and self-sufficiency a virtue.

For the record, I consider ordained monasticism legitimate, and even necessary. Alright, it's not scriptural. So what? Stuff doesn't have to come from the sutras to be valid. If it weren't for monasteries, what would I study? Most Zen teachings are generated, and all are curated, by ordained monks. The typical hermit has been inside before. I have done, and am likely to do again. The monastery is an important touchstone, and a weighty counterbalance to the hippy-dippy narcissism of hermitry. I shudder to think what we would become without it. Finally, it's an effective, irreplaceable practice for many who are drawn to that path, as synonymous to their lives as mine is to mine.

In sum, if I had a million dollars, I'd give it to a monastery. What the hell is a hermit gonna do with money, anyway?

But when the ordained sangha dismiss us homeless brothers as heretics or wannabes, or insist that our sacred birthright path leads nowhere but astray, then I just have to say it, loud and clear:

"Yo, Batman! You got a problem, you talk it over with the Buddha. I got more important lives to live."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)