The just-past issue of Tricycle magazine carried one of the most important articles to come out in the Buddhist press in a generation. Written by my brother Brent R. Oliver, the fact that the title alone (White Trash Buddhist) provokes laughter in many quarters is proof of concept.

The just-past issue of Tricycle magazine carried one of the most important articles to come out in the Buddhist press in a generation. Written by my brother Brent R. Oliver, the fact that the title alone (White Trash Buddhist) provokes laughter in many quarters is proof of concept. For the betterment of the worldwide sangha I'm going to do what they tell writers never to do: send you off-site. The Tricycle website makes Brent's thoughts available only to subscription holders (an ironic if business-savvy twist), but one of those subscribers had the good Buddhist sense to repost it for the rest of us. Therefore, in respect for magazine and writer, I will avoid multiplicating the text all over the Enlightenment Superpath and simply link to that post. Please read it and return for my comments, below.

White Trash Buddhist, by Brent R. Oliver. Tricycle, Winter 2014.

Some thoughts:

- I never felt obligated to pay at my Zen centre, and sometimes I didn't; my teacher was very generous that way. But I still felt like a schmuck, given the inevitable pay-to-pray emphasis in Western Buddhism. I fantasised I'd strike it rich someday, having made my fortune in Zen renunciation, and donate a million dollars in back payments and interest. The fact is, having an institution means planting your lotus in that dirty money-water. The Buddha said it's possible to keep your petals clean even so, if you practice hard enough; Christ flatly cautioned us not to try. Either way, in the great rock-paper-scissors of this life, dollar usually trumps Dharma.

- Brent skirts but does not delve into the effect all this money-think has on the organised sangha. I vividly remember a woman who drove hours to Zen centre in order to join us in sesshin the next morning. She watched me (a resident) arrive from work, overalls and meshback cap covered in sawdust and glue, with clear alarm. As I tugged off my steel-toed safety boots I explained that I punched a clock at a local factory. Soon after, she ran – presumably screaming – out the door, and we never saw her again.

There were undoubtedly other factors in her reaction, mostly relative to her own past and expectations, but the unpretty sight of my blue-collar arse visibly disturbed her. Which is ridiculous. And unBuddhist. And standard in Western Zen. - Brent also appears to need a teacher; his objections to the financial status quo rest on the expense of that relationship. Chances are he's not a hermit. (That is, not even one who doesn't realise it.) Eremitical monasticism is not for all, or even many. Hermits are weird; we'd already been weird for thousands of years the day the Buddha joined us. But I'd love to sit down with my brother over tea and discuss his options. It'd be a damned shame (no pun intended) if he left the path entirely, when there are alternatives that might resolve, in whole or in part, his suffering.

One way or the other, I wish him the best. He's right; Buddhism in the West has become a comfortable little bourgeois club, where we share organic snacks, indulge in exotic Asian choreography, and expect – nay, oblige – tidy little professional values. Ironic, given our hippy origins, but our religious institutions have turned out, all these years later, in many instances, to be so many little boxes.

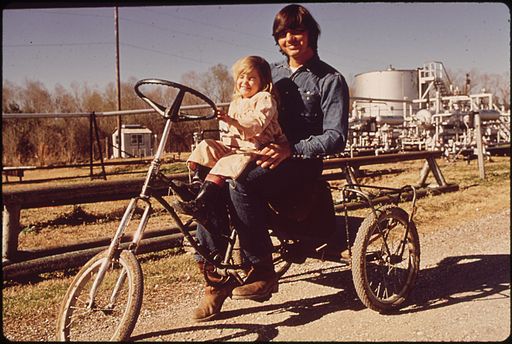

(Photo of a working man riding his daughter on a homemade tricycle, courtesy of John Messina, the US Environmental Protection Agency, and Wikimedia Commons.)

0 comments:

Post a Comment